All the Rage

I Worry That I Know How the Story Ends for Ray Rice and Janay Palmer

Perpetrators of intimate-partner violence usually follow recognizable patterns. So do the conversations we have about famous abusers.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

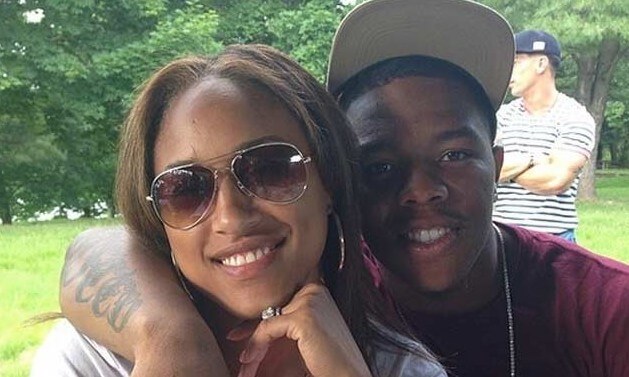

I’ve been thinking a lot about Janay Palmer, over the last few days. I hope very much that the wife of Baltimore Ravens running back Ray Rice has reason to sincerely believe her husband has changed since he knocked her out and dragged her limp body out of an elevator last February. I hope that when she spoke with NFL commissioner Roger Goodell on June 16, and told him the beating was a “one-time event,” she was being honest—and that she will never be proven wrong.

I hope that when she apologized for her own role in the incident, it was because she felt genuinely sorry for doing something we didn’t bear witness to—something just as unforgivable as beating a person much smaller than you unconscious. (That still wouldn’t excuse her then-fiancé’s behavior, but it would help me understand her sense that she owed her husband and the public an apology.)

And I hope that when she decided to marry Rice even after he stood over her limp body, looking inconvenienced by her failure to remain conscious, it’s because she had a 100-percent-accurate crystal ball that predicted a future full of nothing but love and gentle respect from this man.

I would like to believe all of these things are true, because then I wouldn’t have to worry about Janay Palmer. Specifically, I wouldn’t have to worry that all this talk about what her husband did is blowing back on her at home right now, in the form of verbal abuse, controlling behavior, and perhaps more physical violence. I wouldn’t have to worry that the spotlight currently shining on Ray Rice—and the paltry two-game suspension Goodell “punished” him with—is making him feel mortified and victimized, a dangerous combination in a man with a history of violence. If all of those things are true, I can believe he’ll never do anything like that again, instead of assuming that, like most people who abuse their partners, he will continue to escalate the violence over time. And I can quit worrying that eventually, like more than three women a day in the U.S.—such as Kasandra Perkins, the girlfriend of Kansas City Chiefs’ linebacker Jovan Belcher—Janay Palmer will die by her partner’s hand.

That’s what I think about when I watch that video of Ray Rice pulling Janay’s seemingly lifeless body out of the elevator: the cycle of abuse, and how unlikely it is that someone who cold-cocked his fiancée had never laid a hand on her before and never will again. That and certain statistics, like how women are killed by intimate partners at twice the rate of men, and black women killed by spouses at twice the rate of white women.

Yet somehow, people like ESPN’s Stephen A. Smith, as you’ve no doubt heard by now, can still look at that video and think, “Now is a good time to talk to women about what they do to provoke violence.”

Look, I know—because he’s told us 750 billion times now—that Smith really doesn’t believe he was victim-blaming or rationalizing abuse when he said:

And I think that just talking about what guys shouldn’t do, we got to also make sure that you can do your part to do whatever you can do to make, to try to make sure it doesn’t happen. We know they’re wrong. We know they’re criminals. We know they probably deserve to be in jail. In Ray Rice’s case, he probably deserves more than a 2-game suspension which we both acknowledged. But at the same time, we also have to make sure that we learn as much as we can about elements of provocation.

The problem is, people never think they’re victim-blaming. They think they’re taking a rational, thoughtful, admirably unemotional look at both sides of a story. What they fail to take into account is that in this particular story, one side did the punching, and the other side did the falling unconscious. These are not equal positions.

Q. What provokes a man to knock his fiancée out cold?

A. Something going on with him. Aggrieved entitlement, lack of impulse control, displaced anger, a group of friends and colleagues who routinely dehumanize women, the knowledge that he’s unlikely to suffer any real penalty for it, you name it.

Q. What can one person do to deserve getting hit in the face during an argument, let alone by someone claiming to love them?

A. Not one goddamned thing.

It really is that simple. The test is two questions long, and yet, so many of us still flunk it.

We hear story after story of athletes, entertainers, and politicians committing intimate-partner violence, and each time, reporters and op-ed writers remind everyone of the sobering statistics. Inevitably, commenters say shit like, “But she married him anyway,” and “Maybe it was just the once,” and, “What, should he be prevented from ever holding a job again?” So then the reporters and op-ed writers remind everyone of the reasons why women stay with their abusers (Hint: It often involves a legitimate fear that they’ll be killed if they try to leave), and that the majority of people who abuse a partner once will do it again. They point out that saying, “Abusive people in highly visible (not to mention highly remunerative) positions normalize intimate partner violence in our society” is markedly different from saying, “Anyone who’s ever hit a partner should be unemployed, homeless, and starving.” Perhaps we could settle for just not making role models and heroes of them?

And then nobody learns anything, and we do it all over again.

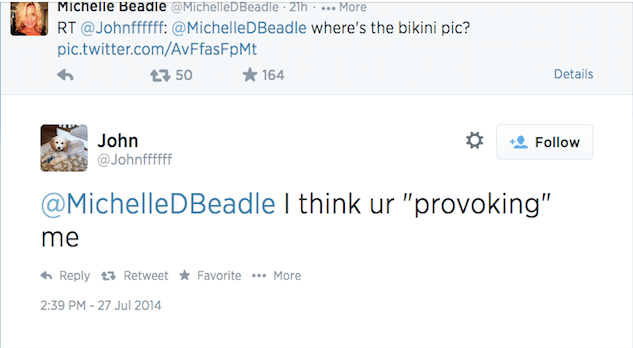

There have been bright spots in the coverage of Ray Rice’s pitifully brief suspension. Keith Olbermann—not always the greatest champion of female victims of famous men—delivered a righteous rant that warmed my icy heart. And ESPN’s Michelle Beadle went off after Smith’s “elements of provocation” speech, disclosing that she’s been a victim of intimate-partner violence and calling Smith’s remarks “irresponsible and disgusting.” As if that weren’t enough, her Twitter responses to demeaning jackasses over the last few days have been delicious.

But then, sometimes the jackasses don’t know when to quit:

And sometimes, men who insist that they take domestic violence with the utmost seriousness can’t stop saying, “But, but, but …” even as they apologize.

“My words came across that it is somehow a woman’s fault,” said Smith on Monday. “This was not my intent. It is not what I was trying to say. Yet the failure to clearly articulate something different lies squarely on my shoulders.” He wisely makes no further attempts to articulate that “something different,” but the damage is done. In fact, he was perfectly clear in his original off-the-cuff remarks and his Twitter follow-up: He believes women have a role to play in preventing domestic violence, at the individual level. He believes victims should try to protect themselves by being aware of what might set their abusers off, and avoiding that behavior.

I have no doubt that Smith offered this advice in a spirit of sincerely wanting to prevent pain and suffering to women. He was thinking about how to intervene before the abuse happens, instead of after a woman is already bloody and bruised. But what he failed to recognize, as he mansplained abuse to an audience that includes both victims and perpetrators, is that people who suffer intimate-partner violence already spend a great deal of their emotional energy trying to anticipate and head off the next incident. Victims will change their behavior, their appearance, their jobs, their habits and religions in hopes of keeping their abusers happy. They’ll cut off family members and close friends who threaten their violent partners’ sense of control. They’ll blame themselves and run themselves physically and emotionally ragged, trying to make sure the man they love never decides to hit them again.

But usually, he does.

Telling victims of domestic abuse to consider how they can prevent further violence is as ludicrously redundant as telling a tightrope walker he should think about how to prevent falling. “You know that thing you’re focused on at every moment, because your life might actually depend on it? Here’s my advice: Focus on that thing!”

Victims of intimate-partner violence don’t need sports journalists to condescendingly suggest they do something they’re already doing. But they could really use a few more like Michelle Beadle, Jane McManus, Will Leitch, and Keith Olbermann, who are willing to call out the NFL, sexism in sports culture, and colleagues who say boneheaded, victim-blaming bullshit. And it sure wouldn’t hurt if more people in the general public paid attention when reporters and op-ed writers explain for the zillionth time how domestic violence actually works.

For now, I sincerely hope Janay and Ray Rice are the exceptions to the rule.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.