Congress

This Is Why Sex Ed in the U.S. Is a Disaster

Thanks to government-funded abstinence programs and a lack of instructor training, some teenagers don't even understand menstruation.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

When Stephanie* began working as a reproductive-health educator in a school-based clinic, she had her work cut out for her. The initial hurdle: convincing the students of confidentiality. Her teenage clients found it hard to believe that they wouldn’t get in trouble for being sexually active. But once she earned their trust, the questions they had for her were astonishing—in fact, she was taken aback by the misconceptions that her middle- and high-school patients had about sex, reproduction, and their bodies.

“I had 16-year-old kids coming in who didn’t know why they were having their period. And these are kids who are sexually active,” Stephanie said.

She wondered what they were being taught in their health classrooms—they seemed ignorant of basic anatomy. Once, waves of students came in to get tested for HIV, even though they reported they weren’t having sex. She discovered that their health instructor had told them they could contract HIV from casual contact.

Such misinformation was dangerous. “Now they don’t know how to protect themselves during sex,” Stephanie said, “and they’re going to shun people who are HIV positive, or who have family that’s HIV positive.”

But even worse for the students than receiving misinformation, she said, was getting no information about sexuality at all. “It gives kids the idea that it’s not even appropriate to ask questions,” Stephanie said. “They’re embarrassed to ask, and then they do the craziest things.”

How did it come to pass that schools, supposed places of learning, have fostered an environment where young people are afraid to ask questions? And where sex is associated with shame and secrecy? For those who remember their sexuality education—if they received any at all—this may sound familiar. Or perhaps not at all. Because one student’s experience can vary wildly from another’s, within the same state, district, or even school. The inconsistency stems, in part, from the existence of a number of federal funding streams for sex-ed programs. The Administration for Children, Youth, and Families (ACYF), for instance, administers two very different initiatives: the Personal Responsibility Program (PREP), which requires educators to provide students with medically accurate and age-appropriate sex education, and Title V, an abstinence-only-until-marriage program.

Title V was enacted as part of the Welfare Reform Act in 1996, with support from conservatives like former Senator Rick Santorum (R-PA), and has since allocated $50 million annually to state governments. The funds are funneled to either media campaigns, or to schools and community-based organizations. Title V delineates an eight-point definition of abstinence-only education, which includes the teaching that “abstinence from sexual activity outside of marriage is the expected standard for all school-age children” and “that sexual activity outside the context of marriage is likely to have harmful psychological and physical side effects.” In addition to withholding information on contraception, abortion, and relationships, this language negates the very existence of LGBTQ students, many of whom, depending on the state, may not have the option of marrying.

President Obama’s proposed FY 2015 budget recommended the discontinuation of Title V, but the program was extended, along with PREP, for one year. According to Jesseca Boyer, Director of Public Policy at the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States (SIECUS), “it remains unclear whether this compromise that enabled the one-year extension—with no mention of either program in the Senate hearings, and only a few related questions on the House side—will continue.” In light of the recent midterm elections, which resulted in a Republican-controleld Congress, however, it seems doubtful that Title V will be terminated come September 2015—and in fact we will likely see more egregious legislation on sexual and reproductive health issues.

ACYF also supports a program called Competitive Abstinence Education (CAE), which targets “high-need youth” (identified as LGBTQ youth, youth of color, runaways and homeless youth, and young people in foster care) to the tune of $4.7 million per year, based on the assumption that abstinence is the best policy for these adolescents, who present a higher risk for unplanned pregnancy. (This seems to preclude the existence of rape, for which many of these teens are also at higher risk.) On the other hand, the President’s Teen Pregnancy Prevention Initiative (TPPI), a wider-ranging—though not entirely comprehensive—approach, was launched in 2010 and devotes $110 million in funding to medically accurate and age-appropriate programs to reduce risk behaviors for unplanned pregnancies.

States, therefore, have access to diverse funding streams for sex ed, and complicating matters further is the fact that each state often has its own policy. Thirty-three states mandate HIV-prevention education, for instance, while only 22 mandate sex education, and even fewer—13—require that instruction be medically accurate. Many states also have what are known as “if, then” laws—in other words, a set of requirements for what must be taught in the event that sex ed is provided. Alabama, for example, mandates that when given, sex ed must include information about contraception, but also stress abstinence, the importance of keeping sex within marriage, and negative outcomes of teen sex; it does not require schools to discuss sexual orientation.

Diana Thu-Thao Rhodes, Associate Director of State Policy and Partnerships for Advocates for Youth, a non-profit that promotes comprehensive sexuality education, noted that despite state mandates, the nature of sex-ed programs is often determined at the community level. “Education policy is very home-ruled in the United States,” Rhodes said. “States and local community members want to have control over the education that their children are receiving, rather than having the federal government telling them what to teach.”

Furthermore, Rhodes pointed out that states lack any mechanism to ensure that individual districts and schools are in compliance with their mandates. “Like any policy really, unless everyone is implementing it, it’s very difficult to enact,” she said.

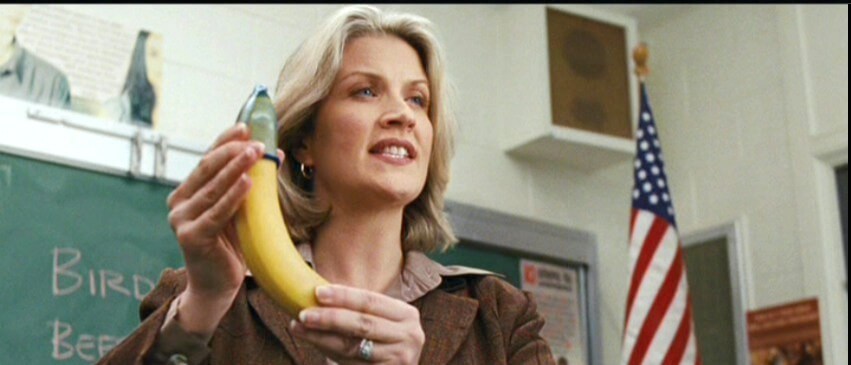

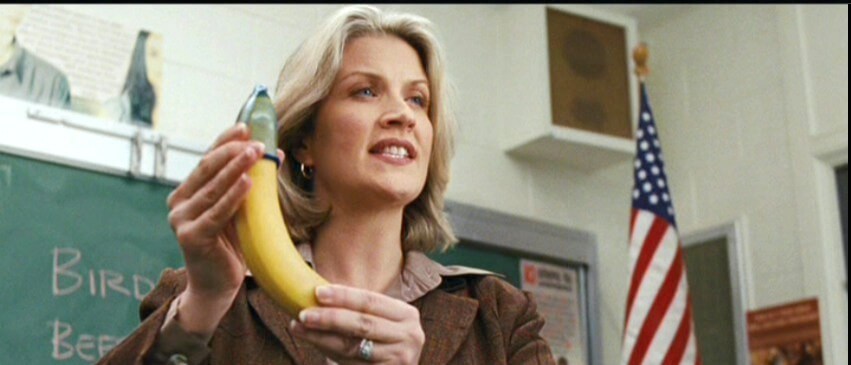

Another root of the inconsistencies in sexuality education lies with individual instructors, few of whom receive sex-ed-specific professional development. “If you’re going to teach high-school math, usually your education degree has a focus on that,” Rhodes said. “Sexuality education doesn’t have those standards.” Often, a health or physical education teacher is also responsible for sex-ed instruction, which administrators expect them to handle without training them to address subjects like STIs, pregnancy, and healthy relationships—hence the misinformation about HIV given by the teacher at Stephanie’s school.

This lack of teacher preparation is reflected in many of the individual experiences that young people have had with sex ed. Kate*, who attended public school in Virginia, remembered that her teacher “made it known that men can’t be raped by women. She was very adamant that it was a women-only issue, and that guys can’t feel the same way women do because they ‘like’ sex. I tried to give her an example of circumstances where a guy was raped by a woman, and she blew it off.”

Melissa* was educated in Maryland, and said that in her class, “enormous amounts of useful information were withheld.” Her instructor did not address pregnancy, contraception, or abortion. She remembered playing “this hand-shaking game to teach us about spreading STDs. Its message was along the lines of, remember, you’re having sex with everyone the other person has had sex with, too. Yet somehow the conclusion was not to wear condoms for penetrative sex, which I still don’t understand. Why did we play that game?”

Chris*, who grew up in Alaska, recalls a sex-ed instructor who mostly read a script from a binder. “The factual misinformation wasn’t nearly as damaging as the sexual scripts, and the establishment of false norms,” he said. “For example, they warned that if a woman spent too long kissing a boy, maybe he’d be unable to overcome his impulses, and keep going.” He added that scare tactics were rampant, with “slides of gnarled penises” shown to students to teach them about the negative outcomes of sex. “It wasn’t until college that I picked up some brochures in the health center waiting room and realized STIs could be cured,” Chris said.

But by college, the information has arrived too late for many students. The media has reported a what appears to be a rising number of cases of sexual assaults on college campuses—and the universities’ inept responses to it, as we’ve seen at Columbia University, where student Emma Sulkowicz, has vowed to carry her mattress until her alleged rapist is expelled. The issue of sexual assault on campus may be nothing new, but Diana Thu-Thao Rhodes sees a link between stories like what’s happening at Columbia and shoddy sexuality education at the middle- and high-school levels. “We have young people not knowing what consent is and isn’t,” Rhodes said. After all, sex ed is more than just anatomy; it relates, Rhodes said, “to issues that affect young women, specifically when it comes to body image, beauty standards, consent, relationships, and dealing with sexual assault and harassment. Those are the conversations that we’re not having in a lot of sex ed classes across America.”

Stephanie agreed that incomplete sex ed is particularly damaging to young women. She spoke with female clients who had never been taught about contraception, and who believed they could prevent pregnancy by douching with vinegar after sex. It is alarming that America’s public schools, which are ostensibly designed to help prepare students for adult life, are sending young people into the world so ill-prepared to protect their own health.

The absence of comprehensive sex ed leads to young people who are out of touch with, and ashamed of, their own bodies, Stephanie said. “To me, it’s the basis of sexual harassment, and culture that is anti-woman and misogynist.” What is the likelihood that a young woman who is estranged from her own body will have the wherewithal to express her needs during sex? An education system that does not teach girls empowerment, or boys accountability, reinforces a culture that is hostile to women and welcoming to predators.

A report released earlier this year by SIECUS, which examines adolescent health indicators in Mississippi, puts the lie to the premise that avoiding discussion of sex will prevent young people from having it. Prior to 2011, Mississippi did not mandate sex ed at all; it now requires abstinence-only or abstinence-plus programs (which may include instruction on contraception, STDs, and HIV/AIDS), but with restrictions that prohibit the teaching of things like condom application and abortion. It also prohibits males and females from being taught in the same classroom. Data reveal that the state ranks second in the country for teen pregnancies, as well as gonorrhea and chlamydia infections. Fifty-eight percent of Magnolia State teens report being sexually active, versus 47 percent of teens nationwide, and are twice as likely to have sex before the age of 13. The idea that avoidance and proscription lead to abstinence has been proven a fantasy throughout American history (think Prohibition). The continuance of abstinence-only programming suggests a near-religious adherence on the part of the states that mandate it, a blind faith in the method despite empirical evidence of its ineffectiveness.

In addition to leaving adolescents ill-prepared to avoid unwanted pregnancy and STIs, abstinence-only language alienates LGBTQ youth, by promoting heterosexual marriage as the only appropriate setting for sexual activity. For LGBTQ young people, Rhodes said, “the sex ed classroom often doesn’t feel safe, and it doesn’t address a wide range of gender expressions and identities,” which impacts how they navigate adolescence. Some LGBTQ youth lack a refuge in their own homes; to deny them one at school can exacerbate their sense of isolation.

Any given student’s experience of sexual education, then—if she receives it at all—is subject to a staggering range of forces: congressional budgeting, state policy, school compliance, community climate, instructor competence. Often forgotten amid the clamor is an adolescent’s right to an understanding of, and ability to make decisions about, his own health. Advocates for comprehensive sex ed see a clear line between curricula riddled with misinformation, and early pregnancy, STI rates, sexual assault, and substance abuse and depression among LGBTQ youth.

Answer, a national organization based out of Rutgers University, offers some solutions to the quagmire of sex ed in the U.S. In a collaboration with Advocates for Youth and SIECUS, Answer has developed a National Sexuality Education Standards for grades K-12, a holistic plan that counts as essential content issues pertaining to anatomy, puberty, identity, pregnancy, STIs, healthy relationships, and personal safety. Like the Common Core standards, Answer’s program outlines clear expectations of what students should know by the conclusion of their courses; it also encapsulates pre-service training, as well as ongoing professional development and support for instructors.

Advocates for Youth takes a grassroots approach, by training young activists to share their experiences and petition their school administrations directly for more comprehensive programs. Rhodes emphasized the importance of involving adolescents in the process. “You can have a program that you think is really awesome, but if it doesn’t resonate with young people, then you’re not going to have any results,” she said.

Chris observed that today’s adolescents have access to resources previous generations lacked: “Kids these days have the Internet, and it’s amazing for them,” he said. “But we were groping in the dark. With Newt Gingrich’s legislation as our best headlight.”

Websites liked Scarleteen, founded in 1998, indeed aim to provide the resources many schools fail to; Dan Savage’s unfailingly frank column, “Savage Love,” has also served as an educational tool for many confused young people. New York City, where Stephanie worked, employs a model that is considered relatively progressive, by offering a number of adolescent-focused clinics, which teens can find through a Department of Health phone app. “It’s awesome that we have that, but the education the clinics provide should be offered in public school,” Stephanie said. She pointed to countries like Finland—where 9 teens per 1,000 give birth, as opposed to 55 per 1,000 in the U.S.—where basic sex ed begins in kindergarten and continues throughout high school. “If we had a system that normalized sexuality from the beginning, it would just be a normal science class,” she said. “But it’s a cultural thing. Our values dictate that this is something we shouldn’t be talking about.”

* Names have been changed

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.