How It Is

Dear Black People, Please Stop Shaming Your Kids On Social Media

"Tough love"—like spanking, and humiliating kids with "Benjamin Button" haircuts—is not an effective way to discipline children. In fact, it is likely doing more harm than good.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Why are some Black parents publicly shaming their children on social media in the name of responsible discipline and good parenting? And why do so many people find pleasure in the spectacle of violence by watching and sharing the public humiliation of Black youth?

Most Black parents are not guilty of this, but the fact that we’re seeing this on our social media feeds means that there are too many.

On the surface, it might seem relatively harmless: A parent photographs his or her child holding up a sign confessing sins like missing a curfew, skipping school, failing a test, dressing provocatively, acting “too grown,” lying, and stealing. Private punishment becomes public humiliation as these images go viral. Folks who see and share it applaud the parent for being strict and doing what they can to keep these wayward Black kids out of gangs, prisons, and morgues.

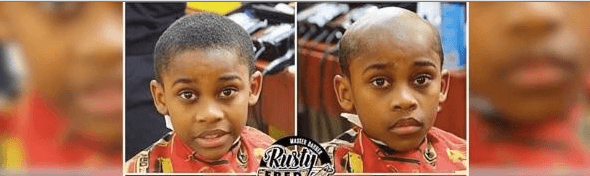

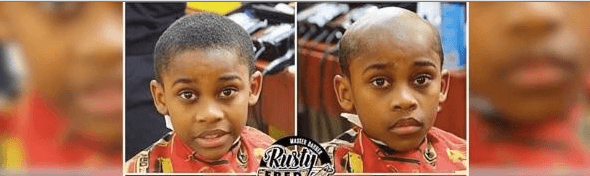

Recently, an Atlanta barber named Russell Frederick has been giving free “Benjamin Button” haircuts out of his A-1 barber shop to kids, whose parents want to use this kind of humiliation as a way to discipline them. Frederick is participating in a longstanding American tradition of public ridicule and demonization of Black boys and girls.

Frederick’s method was recently featured on a TV news segment, in which a trio of anchors—a White woman, a White man, and a Black man—debated whether humiliating a child is an effective tool for discipline. The White woman celebrated the approach. The White man challenged it, saying that humiliating children is not a good alternative to spanking. And the Black man—apparently the only parent in the group—said he found it effective when he did this with his teenage son, adding that he would NOT do this to a daughter.

As Frederick told the Washington Post, “Parents are at a loss. When you go to discipline kids these days, they can’t necessarily use physical punishment the way parents did in the past, but they have to do something. If you don’t, and your kid ends up doing something crazy, everyone is going to say the problems started at home.”

Physical abuse has been eliminated from a parent’s arsenal because of (White) liberal policies. People are defending this so-called “novel” approach by arguing that the haircut is a creative and non-violent way to convey to their kid that misbehavior has negative consequences. But the logic of this form of punishment embodies an unwillingness to recognize that there are emotional repercussions, not least of which the mental scars that are hard to heal.

The issue isn’t just about disciplinary haircuts—although given the nature of Black hair politics, we should reflect on why the significance of waging war on the scalps of Black children is so damaging—but rather the issue of using public humiliation to get children to obey their parents. When the hair of a child is altered in an effort to make them look ridiculous, their peers will ridicule, humiliate, and denigrate them, and this is a form of emotional abuse. Whether it works to curb some children’s behavior is less important than the bigger picture, especially when it comes to Black children in the U.S.

Some of the most popular videos circulating on social media portray parents or other family members spanking kids for acting out well within the range of normal and customary childhood infractions. I am an anti-spanking activist, so I pay special attention to these posts and the commentary they generate, which most of the time cheers on the person for teaching that child a lesson.

And that’s an even bigger problem: People’s need to broadcast their tough-love parenting all over social media. I imagine it bolsters their sense of insecurity and inadequacy in rearing their children, as they seek applause for projecting their strong values and no-nonsense approach. But it also reflects a response to the way Black parents have long been blamed as absent and inadequate, and for social breakdown of our communities. It’s an overcorrection, these public displays of extreme disciplining, a declaration to the world, “Look what we are doing; we are parenting, we are demanding disciplined children, so shut the hell up, America.”

But the extreme discipline has the potential to make these children more vulnerable to violence, and amps up their risk for behaviors that will get them in trouble at school and on the streets. Not to mention Black children are being killed because of a long heritage of racialized ideas about Black children’s bodies, and character.

What boggles my mind about the whack grown-man haircuts is that these parents who are hauling their kids into Frederick’s barber shop seem to have forgotten that 12-year-old Tamir Rice is dead because a trigger-happy cop blinded by those racialized ideas mistook him for a 20-year-old man, and his toy gun for a real weapon.

There are numerous studies telling us that Black children are routinely perceived to be older and therefore treated as such, and more likely to be suspended or expelled from school, disciplined much more harshly, locked up, and even shot by police.

Physically altering a small child’s appearance not only invites ridicule and shame, but feeds into dangerous and potentially deadly stereotypes and myths putting young people in a dangerous situation in a society where there is little distinction between Black children and adults, and where Black kids are already adultified in the cultural mind-set, and accelerated toward social and physical death.

“Nothing is to be gained by making a child feel ashamed of his or her appearance,” says Lisa Aronson Fontes, Ph.D., a senior lecturer at University Without Walls at the University of Massachusetts, and the author of Child Abuse and Culture. “It is difficult enough to grow up with a healthy body image in this culture and especially difficult for African-American children. A child whose appearance is altered in this way may end up being an outcast at school and among peers for weeks if not months or years. We want our children to be happy and have solid relationships. We should not do anything that would make them be pushed away by their peers.”

There is nothing easy about parenting a Black child today, in large part because of the dangers that all Black children face, especially from the police. So it’s understandable that some parents engage in punitive shaming and social-media broadcasting to send the message that they’re laying down the law with their child so hopefully the law won’t lay their child down forever.

Black parents have been working overtime to send this message to authorities: “I’m doing this job so the criminal justice system won’t.” This is something Black folks have been engaging in since the plantation.

If only it were that simple. Because doing so creates a false sense of protection playing on White supremacist narratives that locate anti-Blackness at the feet of Black behavior and pathology. In other words, it works from belief that stop-and-frisk, rates of suspension and expulsion, incarceration or death-by-police is rooted in the undisciplined Black body.

The ballot or the spanking?

Ceaseless agitation or old man’s haircut?

A spanking, a haircut, or standing on a corner announcing one’s failures will not protect Black children; it only gives parents the sense of security that is elusive in a racist and violent nation. Changing Black behavior will not save us. Whipping and humiliation our children will not set us free.

But if the parents of Black children take on the role of overseers, we don’t need plantations or the KKK. And when we do something like alter our children’s appearance we are participating in a dehumanization process required by a White supremacist society. Public shaming tells our children that they have no right to bodily integrity. It shows our children that they cannot count on their caregivers to protect them. So how then can we expect the larger society to protect our kids?

“My initial reaction is that this public shaming, via social media, and picked up by both mainstream print and broadcast news outlets, is a form of psychological maltreatment,” says Nadine Bean, a professor of social worker at West Chester University. The videos “are a way to gain temporary fame and kudos. But the impact of psychological maltreatment is well-documented … and lifelong. They can take the form of insults, threats, public shaming, belittling, being emotionally neglectful, being insensitive, cruel, etc.”

Those photos and videos on social media might be revealing much more about the parents than their child’s disobedient behavior. “A caretaker who posts a video showing him or herself humiliating a child is gloating over holding power over that child,” says Aronson Fontes. “This sounds to me like an adult who feels powerless.”

While some Black parents might see altering a child’s body as a way of protecting them from dangerous behaviors, it’s a denial of the child’s physical, emotional, identity, and cultural integrity. Given the ways that Black hair is regulated and policed in our society, from Hollywood and the military to the Olympics and corporate boardrooms, we have to be aware of the ramifications of turning hair into an arena of discipline for children who have to navigate a society where all the odds are stacked against their entire selves, including the hair that grows on their heads.

In a moment where we’re seeing more news stories about teachers cutting Black children’s hair in class, or being suspended for wearing natural hairstyles, do these actions and videos simply extend the reaction of White supremacist efforts to discipline Black youth into the realm of spectacle?

The long-term consequences of this kind of discipline are more serious than most people imagine. Experts analyzing data from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network for the American Psychological Association found that children who experienced psychological maltreatment or emotional abuse, defined as “caregiver-inflicted bullying, terrorizing, coercive control, severe insults, debasement, threats, overwhelming demands, shunning and/or isolation” suffer in their lifetime from heightened levels of depression, anxiety, attachment problems, substance abuse, and low self-esteem.

Shaming and humiliation masquerading as discipline can harm a child’s attachment to their parents. According to the National Child Traumatic Stress Network, “Our ability to develop healthy, supportive relationships with friends and significant others depends on our having first developed those kinds of relationships in our families. Through relationships with important attachment figures, children learn to trust others, regulate their emotions, and interact with the world; they develop a sense of the world as safe or unsafe, and come to understand their own value as individuals. When those relationships are unstable or unpredictable, children learn that they cannot rely on others to help them.”

There are too many spaces that are already unsafe for Black children. Walking to store is not safe; getting in a snowball fight is not safe. Being at school and the workplace are not safe; hanging out with friends is not about the innocence afforded to White youth. A home that is not safe and empowering does not change the culture of terror but instead normalizes the violence.

The consequences are not long-term but immediate as well. Trauma experts say that children who do not have healthy attachments have been shown to be more vulnerable to stress. They have trouble controlling and expressing emotions, and may react violently or inappropriately to situations. A child with a complex trauma history may have problems in romantic relationships, in friendships, and with authority figures, such as teachers or police officers.

Ironically, this suggests that Black parents who use these disciplinary tactics might inadvertently be making their children more likely to have problems with the very authority figures they’re trying to protect their kids from.

“It is better not to beat children, especially if we don’t want them to fight with others,” says Aronson Fontes. “Nothing is to be gained by inflicting emotional abuse instead of physical abuse. Instead, we should be using positive discipline.”

“There are so many healthier alternatives and none of them involve exploitive images of minor children on social media or mainstream media,” says Bean. “Taking away privileges, time outs (one minute per child’s age), having the child write (if able) about why his/her choice of behavior was not good and what alternative behaviors might be used in the future, and, of course modeling compassionate, humanistic behaviors even in the throes of conflict. There are always alternatives to harsh physical punishment or psychological maltreatment. ALWAYS!”

There is no upside to shaming and humiliating children in the name of trying to improve their behavior. All children need for their parents, teachers and other caregivers to provide discipline from time to time—that’s inevitable.

But with Black children all over the country saying that their greatest wish is “to grow up,” and not be murdered by the police; with a generation of Black children coming of age against a backdrop of #BlackLivesMatter and #ICan’tBreathe, we cannot afford to cause our children any kind of harm, especially in the name of good, responsible parenting and protection from a society set on their destruction. #BlackHappinessMatters #BlackSelfEsteemMatters #BlackEmotionalHealthMatters

So while it might seem that giving a child a punitive haircut to change their behavior is a benign alternative to corporal punishment, and a sign of good, responsible parenting, we must look deeper and do better.

Black children are living in a state of siege, and they need their parents and caregivers to be allies, not adversaries, as they struggle to navigate the difficult maze to safe, healthy adulthood in this country. Their lives are at stake merely by virtue of their race, and their futures are perilous. When we begin to spend as much time focusing on what is inside their heads as on top of them; when we invest in their emotional and psychological well-being as if their lives depend on us doing so, then we will begin to move in the right direction.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.