#BlackLivesMatter

What the Black Lynchings Numbers Don’t Reveal

The EJI’s new report on "racial terror lynchings" is crucial to the conversation about our nation’s long, violent history of racism. As a starting point.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

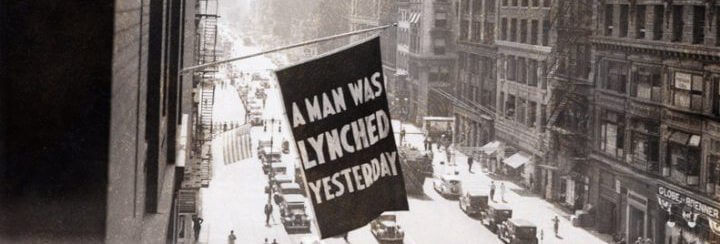

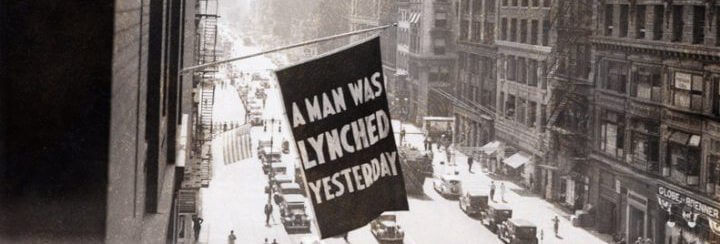

Last week, according to an article by Campbell Robertson in the the New York Times, the Alabama-based Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), founded and run by Bryan Stevenson, released a new report on the history of what they call “racial terror lynchings” that occurred across 12 states in the American South, from 1877 to 1950. Subsequent media coverage focused on the report’s finding of 3,959 African American victims. (In the report summary, the authors distinguish the “racial terror lynchings” they studied from the more popular hangings and mob killings that “often followed some criminal trial process or that were committed against non-minorities without the threat of terror.”) This report comes on the heels of news of Northeastern University law and journalism students’ work documenting racial killings from the Jim Crow era. These and other projects reflect a growing commitment to restorative justice for anti-Black violence that White officials historically refused to punish.

The EJI report focuses not only on the lynchings that are most familiar to many Americans—the ones that were attended by hundreds or thousands, documented by photographers, and where White lynchers and spectators took trophies. It also studies the smaller, less spectacular killings that were more common in White southerners’ use of violence to punish and discourage African Americans’ resistance to White supremacy. The researchers’ inventory is thus likely to add more depth and breadth to knowledge of lynchings’ widespread and terrorizing nature. As helpful as the report will be—particularly with its beautifully designed graphics and enumerated statistics of the killings— what it won’t do is give us a sense of the suffering this violence caused, unless we use the report to begin a much deeper, more substantive conversation about the lived consequences of these killings for the African Americans who experienced them.

As many reactions to the report’s findings show, the number of African Americans White terrorists killed with impunity during the Jim Crow era matters. These figures help us see historical periods when the loss of Black people’s lives to terror didn’t matter and make connections to the present. They also allow us to understand the scale of the nation’s cataclysmic failure to uphold its responsibility for protecting its citizens and ensuring they enjoyed due process and equal protection under the law. As important as the numbers are, they often obscure as much as they reveal.

First, the magnitude of so many killings can render them incomprehensible. Thousands of lynchings in aggregate threaten to overshadow the individual ones. Indeed, numbers this large seem unfathomable and make lynching actually more difficult for people to grasp. This, combined with the span of years since the golden age of lynching, might be why some Americans find it easy to rail against the recent atrocities committed by the Islamic State and be blind to the U.S.’s participation in and tolerance of similarly barbarous acts, and then outraged when people like President Obama remind them of it.

Second, the numbers don’t show the human costs behind the nation’s legal and political failings of its Black citizens. Victims of lynching often lost their identities in death. They went from being fathers and mothers, husbands and wives, sons and daughters, and sisters and brothers—human beings who inhabited the world—to generic “lynching victim.” Consequently, people trying to understand this violence shift from learning more about the individual victims’ deaths and lives and the impact their killings had on their families to what the composite deaths mean for the nation, White supremacy, Black subjection, and the nation’s legal or creative culture.

This erasure of victims’ identities and humanity happened during the era of the killings, and has left a historic mark on present day understandings of this violence. Evidence of this is seen in the persistent academic and popular focus on White perpetrators, state actors, legal proceedings, press coverage, famous anti-lynching crusaders, and the cultural products that emerged. In other words, too many discussions about and writings on lynching focus on everything but the actual Black victims and their families.

Given the EJI’s research of local archives and court records as well as their interviews with victims’ kin, the full report will likely contain the victims’ names and more information about their lives. This would help to individualize, indeed humanize the numbers of the lynching dead, and hopefully inspire academics and the larger public to do the work of connecting victims to their families and the communities in which they lived. When we focus on who lynching victims were in life, we see their social and emotional ties and are reminded that every single victim was part of a family and community that had to live with their killings. Reckoning with the full humanity of lynching victims is one of the best ways to move beyond the numbers, and realize the devastating costs of this level of racial terror.

Another promising aspect of the EJI’s project is their plan to erect historic markers and memorials to lynching. The goal is “to force people to reckon with the narrative through-line of the country’s vicious racial history, rather than thinking of that history in a short-range, piecemeal way.” Such a plan would require filling in the gaps left by the numbers with information about the victims and their families. Markers and memorials to lynching would also enhance ongoing efforts to diversity monuments and address the erasure of racial terror from the nation’s collective memory. They would also acknowledge the victims and their suffering.

Public markers and memorials that honor African Americans or challenge White supremacy won’t be easy to achieve or maintain. Executing this part of their plan will require EJI to confront racists’ and “postracial” enthusiasts’ opposition to monuments that challenge White supremacy. White conservative opposition to monuments and memorials celebrating African Americans or observing moments in their histories is common throughout the South. White residents of Talbot County, Maryland, for example, spent years fighting the installation of a memorial for Frederick Douglass on the county courthouse lawn. Opponents argued that the lawn was reserved for honoring the county’s military dead, including two Confederates, not the famed abolitionist, arguably their most famous one-time resident.

The marker created to commemorate the lynching of Mary Turner, a pregnant woman killed in Lowndes County, Georgia, has been vandalized repeatedly, as have the tombstone of civil-rights activist James Chaney and the historical marker acknowledging his killing along with Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner during the Freedom Summer campaign. For a year, Correl Hoyle has sat sentry and maintained a protest vigil after three White students put a noose around the neck of the statue commemorating James Meredith’s enrollment at the University of Mississippi. These acts of vandalism represent a protracted White supremacist tradition of denying Black people and their allies the right to commemorate individual and collective histories of African-American suffering that allowed racial terror to be erased from the nation’s historical memory in the first place.

At the center of restorative justice projects such as EJI’s and the public’s interest in it is a desire to understand systemic and systematic failings of the criminal justice system and the society from which it emerged and to stitch this knowledge into the tapestry of American history. Their archeological work of recovering lost or little-known histories, interviewing witnesses and family members, and publicizing their accounts is a needed form of redress. However, in excavating the history of racial terror, we need to be careful about how we proceed. The author of the Times’ article identified the victims racially as Black but failed to do the same for the White perpetrators. As many people, including sociologist Crystal Fleming, noted, writing about racial killings in the passive voice (as if they just happened) and failing to racialize the perpetrators minimizes and erases White people’s culpability in the killings. Whether it’s intended or not, refusing to see and name whiteness is part of the larger invisible and often unconscious work of white supremacy.

Even as we identify whiteness and White supremacy’s role in the killings and the ways we remember and forget them, we have to be mindful of the ways such a focus can erase Black victims and victimization and undermine restorative justice’s goals. Barbara Krauthamer also noted the ways the report summary focused on the “trauma of White witnesses and perpetrators” in its discussions of the lynchings’ impact on nation and its people. This is important because the meaning of this history of racial terror for the nation or it’s impact on white people cannot be allowed to stand in for what they meant to the African-American victims’ families.

Americans interested in justice or reconciliation, especially those who believe that Black Lives Matter, must be ready to go beyond the headlines and the statistics. They must reckon with of lynching victims and understand what happened to their families and communities after their killings. Failing to do so allows the dehumanization and objectification of victims to continue.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.