Books

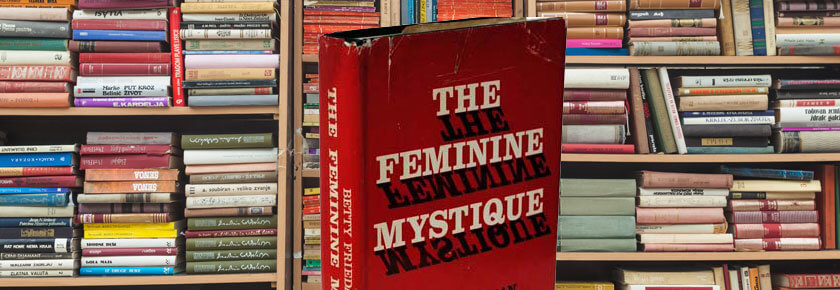

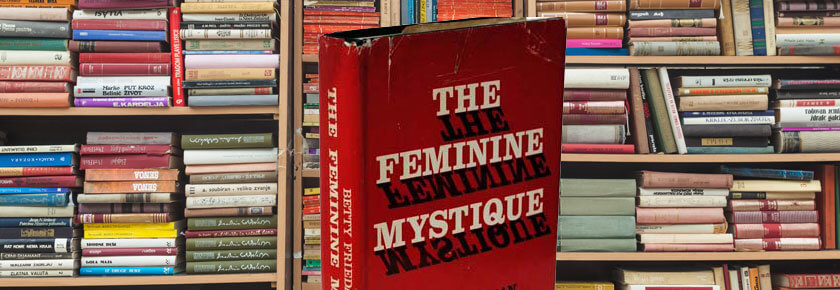

The Eternal Feminine Mystique

The world has changed in the 50 years since Betty Friedan’s groundbreaking clarion call to women. But the feeling burns on.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

When President Obama referenced Seneca Falls at his second inauguration, it sent many of us scurrying to Google. What we found was history. Our history: Seneca Falls, New York, was where in 1848 American women first held a conference to discuss gender equality or, rather, the lack of it. The desirability, never mind the possibility, of getting the vote was one of many topics; others ranged from the right to an education to that of owning property. The ensuing conclusions were put forth in a Declaration of Sentiments. Although we wouldn’t get the vote for another 72 years, it was there, in the scenic Finger Lakes region, that the U.S. women’s suffrage movement was born, earning Seneca Falls the status, as the president rightly noted, as a milestone on the stony path toward equality, alongside Selma and Stonewall.

If Seneca Falls has been forgotten, it’s no wonder we have largely overlooked another landmark: the 50th anniversary of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique.

Maybe “dismissed” is a better word. For Friedan’s 1963 book, the result of five years of research, is now often cited for what it missed: African American women and members of other minority groups are ignored in its 500-plus pages. Working-class women, and those who could not attain a spouse with significant income to support them, are also left out. Friedan’s work – which is being commemorated in a big new W.W. Norton reissue – was aimed at women like herself: educated, white and financially stable. The “cared for” class, you could say. Women who seemed to have no cause for complaint, but who were, for unknown reasons, unhappy.

Indeed, the relative comfort of the women discussed was one of its issues. Why would well-off American housewives, mothers who had wage-earning husbands, healthy children, and modern appliances to make their chores easy, not be satisfied? Turning the tables on another great book about a woman’s dissatisfaction, Freidan noted that, actually, unhappy families all shared a common trait. The “problem that has no name” was our societal irrelevance. For many women of the burgeoning middle class, post-war affluence had made our labor unnecessary. We didn’t have to work, therefore, we shouldn’t want anything more than our biologically dictated role of wife and mother. And as we were moved from irrelevance to incapacitation, we felt it – the emptiness, the depression – that accompanies such emotional foot-binding. As Gail Collins writes in her introduction to the deluxe new edition, The Feminine Mystique was “a very specific cry of rage.” We wanted more. We were more. We were going to take our lives back.

These days, that can seem so old hat. It’s hard to imagine the girls of Girls accepting lesser pay for a gig or being told that their opinions (of sex acts, tattoos, or boho fashion) didn’t count. These days, the debate has moved on to another “successful woman”’s problem: the ability to “have it all” – children and career. Or the impossibility of such an ideal in our current scheme of things, as The Atlantic proclaimed only last summer.

And that’s why Friedan still matters, perhaps as much as Seneca Falls. The heart of this book, it’s great truth, is not so much in its diagnostic qualities of the “housewife’s syndrome.” Those were right on – for a certain class at a certain time – and they helped bring about changes in everything from how we view personal fulfillment to the respect that stay-at-home mothers now demand.

And that’s why Friedan still matters, perhaps as much as Seneca Falls. The heart of this book, it’s great truth, is not so much in its diagnostic qualities of the “housewife’s syndrome.” Those were right on – for a certain class at a certain time – and they helped bring about changes in everything from how we view personal fulfillment to the respect that stay-at-home mothers now demand.

What was bigger is its recognition that women’s experience of the world is valid. That our discontents are civilizations’ discontents and that only a full-court societal approach can address them.

Writing in 1997, Friedan championed the continued legitimacy of this approach, bringing it to bear specifically on parenting and the need for a more equitable solution in an epilogue that’s included in this new edition. She died in 2006, six years before The Atlantic would sound its strikingly similar clarion call and get us all up in arms. It’s a new battleground, but if you look at it closely, the fight’s the same. And maybe every 50 years or so, we need a Declaration of Sentiments. Because what we feel still matters. What we feel is real.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.