Why it’s near impossible to prosecute websites that post naked pictures of people online without their consent. And the case that could change all that.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

It’s a longshot, but there’s a preliminary hearing on April 16th that might just bring about a breakthrough in prosecuting “revenge porn,” the posting of nude or semi-nude pictures of people online without their consent for the purposes of shaming and harassing them.

Right now, the growing scourge is almost impossible to prosecute. The laws were written when the Internet was a nascent cultural force, long before anyone had such loathsome activities in mind. And yet, thanks to a coalition of determined women, attorneys and activists, the legal system might be catching up, albeit slowly.

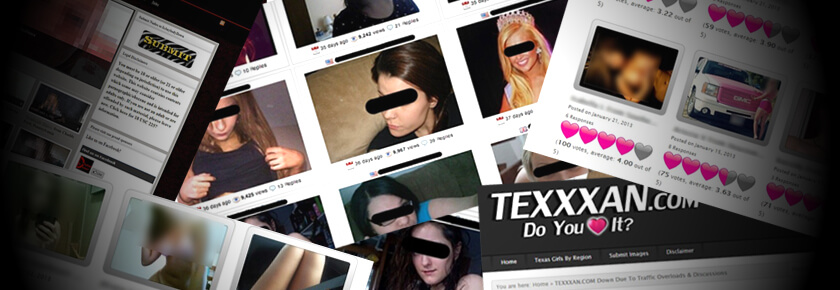

In January, at least 23 women filed a class-action lawsuit against Texxxan.com, and its hosting site Go Daddy, for publishing nonconsensual photos along with personal information, including victims’ names, home addresses and social media profiles. The Arizona-based hosting giant asked to be dismissed from the case, citing the Communications Decency Act of 1996, which states that web hosting companies are not liable for their customers’ content.

And on April 16th, the decision on Go Daddy’s dismissal will tell whether the courts are still willing to rest on that outdated provision or whether they’ll set a precedent with a high-profile case against the world’s largest domain registrar.

Most legal analysts interviewed for this article say it isn’t looking good for the plaintiffs, now a group of 30. Regardless of the outcome, a network of anti-revenge porn advocates, including lawyers, former victims and activist groups such as EndRevengePorn, WomenAgainstRevengePorn and WithoutMyConsent, are working hard to get new laws on the books that would stamp out the activities of Hunter Moore and Craig Brittain, to name two of the most pernicious revenge porn operators. If the battle were drafted in cartoon form, you’d see a cadre of angry women (and some men) chasing these Hot Topic punks away from their coke dens and computers.

For Hollie Toups, the 33-year-old lead plaintiff from Beaumont, Texas, the battle can’t come soon enough. Last fall she found her private photos from six years ago on the now-defunct site. Some she had sent to a boyfriend, others were shots she’d taken of herself to gauge weight loss during a fitness regime that she’d never sent anyone.

For Hollie Toups, the 33-year-old lead plaintiff from Beaumont, Texas, the battle can’t come soon enough. Last fall she found her private photos from six years ago on the now-defunct site. Some she had sent to a boyfriend, others were shots she’d taken of herself to gauge weight loss during a fitness regime that she’d never sent anyone.

“My first reaction was to shut off my computer. I almost looked over my shoulder,” Toups recalled. “You almost want to go through your house right then to see if anyone’s there. This instant paranoia comes over you.”

That paranoia has stayed with her ever since, fueled by strangers propositioning her in public places like the grocery store, or a local restaurant where she was once dining with her Mom. A teacher’s aide, she also had to tell her employer who, thankfully, was understanding.

“This impacts my life, my career and my family every single day,” Toups said. “It’s astounding that someone’s allowed to get away with hurting people this way.”

New Jersey is the only state with a law that makes distribution of revenge porn a third degree crime, resulting in three to five years in jail. Burgeoning legislation is working its way through Florida. But in Texas, Toups’ lawyer John S. Morgan doesn’t have such direct statutes to work with. Instead, he’s pursuing a strategy based around invasion of privacy.

“The hosting companies claim to have immunity and currently they do,” Morgan said. “It’s terrible that there’s no federal law that addresses it. But there is nothing stopping me from pursuing it on the state and civil level.”

On the federal level, a patchwork of laws regarding cyberstalking, as well as the Video Voyeurism Prevention Act of 2004, could feasibly help revenge porn victims. But the problem is “dearth of enforcement,” according to Ann Bartow, a Pace Law School professor who has written extensively about the matter. “For whatever reason, police won’t get involved unless it’s really severe.”

One reason police are unmotivated to go after perpetrators points back to the Communications Decency Act. “Indirectly, it creates a culture that minimizes the problem,” she says. If the hosts aren’t responsible, then the individuals posting the photos on the sites are, but such operators often take full advantage of the Internet’s shifty nature. A case in point: Craig Brittain of IsAnybodyDown has twice closed down his site and transferred the content to a new address to frustrate the authorities, standard practice for revenge porn peddlers.

In other words, if the police can’t pin it to a specific person who’s posting the photos on a current website, what’s there to do?

Some police officers have recognized this problem and are developing laws accordingly. In Florida, the Brevard County Sheriff’s Office in cooperation with state representative Tom Goodson has sponsored a bill that makes it illegal to post any photo or video without written consent. Last month the Florida House subcommittee unanimously voted in favor of the bill that would make posting revenge porn a felony.

It’s progress but according to Mary Anne Franks, a law professor at the University of Miami, the law is “well-intentioned but badly written.” On the plus side, it narrows in on contextual consent, the fact that a person may send a nude photo to a boyfriend for his private enjoyment, but not for him to post online with her LinkedIn profile. It also takes the important step of criminalizing revenge porn but it’s so broad, Franks says, “that it probably does violate the first amendment.”

The first amendment protects consensual pornography but is it relevant to “revenge porn”? Despite its attention-grabbing name, revenge porn is really a form of cyber-harassment that utilizes the porn-entertainment complex. It isn’t even always sexy, by the classical definition. Some sites have shown hacked photos of women who were photographed after breast reduction or implant surgeries, or women who were filmed undressing in a changing room without their knowledge.

Franks believes it could also tie into much darker forms of sexual assault, including sex trafficking. “One of the ways that women are controlled in trafficking situations is by threatening to take photos and videos of her and give them to her family.” It’s likely, Frank says, that in a culture that disseminates photographs without consent, that these images have found their way onto a revenge porn site.

“The revenge porn industry shouldn’t be entitled to first-amendment protection,” Morgan says. “This is not consensual like porn; this is nonconsensual.” Morgan points out that Texxxan.com not only featured unauthorized photos of adults but also underage girls, which federal law clearly forbids.

Despite the flaws in the Florida proposal, criminalizing revenge porn is necessary for changing the way these cases proceed in the courts.

At present, a victim of revenge porn requires the resources to hire a lawyer for a long and possibly expensive civil court battle. Toups, for instance, came to “an agreement” with Morgan but she worries about money. “I’m not rich. I can’t pay him forever.”

For victims without financial means, the next best thing is a tough-ass mother willing to directly tangle with revenge porn’s most notorious kingpin. After her daughter, Kayla Laws, found photos of herself on Hunter Moore’s IsAnyoneUp last year, Charlotte Laws leapt into action. The Los Angeles writer, activist and commentator on NBC’s “The Filter” relied on her former experience as a private investigator to pinpoint Moore’s site and ask his host, BlackLotus Communications, to block the page with her daughter’s photos, as well as photos of other victims.

“It was a huge ordeal,” Laws says. Her investigation prompted the FBI to open a case on Moore. After Laws talked to dozens of his other victims, many of whom had been hacked like her own daughter, she tweeted Moore’s home address in Woodland, California, to help anyone “process service” against him. Her provocative gesture sparked off a battle between the two, with Laws receiving viruses, death threats and a suspicious visitor parked outside her home. Anonymous, the crusading hacker group, stepped in to “hold Moore accountable,” ousting more personal information about him.

Moore’s house was raided by the FBI last summer, and his site is gone for now but Laws, a former city commissioner for Los Angeles, has moved on to advocacy. She has a meeting with Democratic state representative Brad Sherman next week and will also be meeting with congresswoman Janice Hahn soon.

“The good thing about getting laws passed on the state level,” Laws said, “is that the more states that do it, the better chance it’ll get done on a federal level.”

New York-based management consultant Carla Franklin is another cyber-harassment victim who not only fought back against her cyberstalker but has moved into advocacy. After a few casual dates with a man she met at a networking party in 2005, Franklin became the target of a six-year harassment campaign that included hacking into her former cell phone and sending sexual messages to business associates and friends. She now has a pending lawsuit and an order of protection against him.

New York-based management consultant Carla Franklin is another cyber-harassment victim who not only fought back against her cyberstalker but has moved into advocacy. After a few casual dates with a man she met at a networking party in 2005, Franklin became the target of a six-year harassment campaign that included hacking into her former cell phone and sending sexual messages to business associates and friends. She now has a pending lawsuit and an order of protection against him.

In addition to several public speaking engagements, in the last few years Franklin has met extensively with New York Senator Eric Adams, supplying his office with research she gained from her own experience. (Though not a lawyer, Franklin wrote her own subpoenas and harassment lawsuit.)

Franklin has been following the Go Daddy case. “I hope they’re not dismissed. It needs to set a precedent. People are getting sick of this. I do think people are recognizing that cyber-abuse is a growing problem and that it won’t go away.”

Toups also hopes that putting her face and name out there as a victim will help shift the tide, no matter how Go Daddy fares. “I never thought the case would gain this much media attention, but now that it has, I’m ready to fight. It makes me even more determined.”

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.