Feminism

DAME Exclusive: Pussy Riot Letters From a Moscow Jail

Get the first look at correspondence from imprisoned Pussy Riot member Maria, provided by the one journalist she was allowed to speak to from behind bars.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Masha Gessen is a Russian-American journalist and critically acclaimed, best-selling author of The Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin. A longtime resident of Moscow, she has recently moved with her partner and three children to New York, to protect her family from Russia’s recent (and ongoing) punitive anti-gay legislation. Her new book, Words Will Break Cement: The Passion of Pussy Riot, was published last week by Riverhead Books, to coincide with the release of two of the activist art group’s founders, Nadya Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina, who were convicted of “hooliganism” in 2012. Both mothers of small children, they served more than 650 grueling days behind bars apiece for 40 seconds of lip-syncing in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior, enduring physical abuse, sleep deprivation, dehumanizing sanitary conditions, and intimidation, along with severe undernourishment brought on by repeated hunger strikes. Gessen corresponded with both women while they were in detention, and was the only journalist to interview Tolokonnikova in prison; in addition, Alyokhina, at great personal risk, made available to her letters written to a friend that capture details of contemporary Russian prison life, including those reprinted here.

Undated (early March)

Olya,

I have not yet seen your letter, though I know there is one. My lawyer will come tomorrow and give it to me, and I will hand over this response, which I am writing half blind.

Maria meant that she was writing the response without having seen her friend’s original letter.

I spent the last three days in quarantine, a very cold cell where everyone lands upon first coming to pretrial detention. It is a museum of conceptual art. The windows are caulked up with bread crumbs; there are many many many bread crumbs and it’s not clear what holds them there. There are 12 beds and they are welded to the floor.

There are six bedside tables and they are welded to the floor. It is cold all the time. We slept in our overcoats and fur coats and the cold still woke us up. Do you remember the museum in Vilnius?

They had gone to the Genocide Museum in Vilnius together. The building had housed a succession of exterminating governments’ courts and police headquarters—the

Russians, the Germans, the Soviets, the Nazis, and the Soviets again, with a KGB prison in the basement. The prison’s nineteen intact cells form part of the permanent exhibit; among them is a cell where the floor is a pool of freezing water and the prisoners had to balance on a tiny round platform in the middle until they nodded off and fell into the water.

This place is like that museum, only more frightening. But this fear mixes with incredible beauty—if only you can keep looking at all times, if you can keep letting it all in—you will feel a force capable of knocking out all the glass windows, twisting the rusty grates, turning to dust the concrete flooring of the inner courtyard where we are taken for an hour a day and where the snow shines for a few seconds after it falls through the squares of the ceiling grate and then mixes with the gray-brown mass underfoot, spotted with cigarette butts.

I am reading a book by Kuprin. It was the only thing here. You cannot have your own books in pretrial detention, and the library is a myth: to get anything out of it, you have to go through utter hell. That is exactly what I am planning to do in the next few days, and I hope to succeed.

Forgive me for such an apolitical letter. There was a lot that was good. Really. Really, really. I guess someone else is fated to get a letter full of joy and calls to action. I miss you. I miss you a lot. A lot.

Inmates had the right to correspond by e‑mail—as long as family or friends initiated the correspondence and paid for their own letters and those they got in return; the rate was fifty rubles, or just under two dollars a page. E‑mail was read by prison censors. The other way to correspond was to pass paper letters through the defense attorney; this was officially forbidden but tacitly tolerated, for the most part. Maria used this uncensored route to correspond intensively with Olya Vinogradova, her institute friend.

March 28, 2012

Dear Olya,

First of all, please forgive me for writing about food so much in my previous letters. It’s just that I was embarrassed that the girls, my cellmates, were always treating me and I had nothing to offer them. Yesterday volunteers sent so much food that all of us in this cell are set for at least two weeks. Thank you so much!

As soon as word of Nadya’s and Maria’s arrests got out, a spontaneous ragtag support group formed; it would stay together for much of the next couple of years, with friends and strangers collecting money, food, and paperwork to help the inmates. Once friends published the lists of foods the inmates needed, there was a rush on the pretrial detention facility’s online store, with people ordering food to be delivered to Maria’s and Nadya’s cells. It was particularly important in Maria’s case since she was a vegetarian and could not eat most of what was delivered to the cell from the kitchen.

I really do feel all right here, and I think that if I have to spend half a year or a year behind bars, it will only make me stronger. There was a lot of misunderstanding at first, but now people support me even if they do think I am a little cuckoo. Among other things, the girls in the cell have been teaching me not to be naive and not to believe all the incarceration stories I hear. But I still believe everyone. I have always thought that all people are good and we need to separate their deeds (which are often not good) from the people themselves. To put it simply, everyone has a right to make mistakes. I know everything is not quite so simple and crude, but here, as I reiterate some basic things a hundred times over, I actually learn something.

“Half a year or a year” sounded unimaginable to Olya. Maria’s first arrest order was for two weeks, and this seemed like an impossibly long time. Then there was a hearing and the term of arrest was extended by a month, and this was shocking. In April, a judge ordered Pussy Riot held for another four months, and Olya started getting used to the idea that time behind bars could indeed be measured in months. By this time, the prosecution was talking about years.

Spring came yesterday. Pigeons are cooing by our window. The sky is slightly overcast right now, but when the sun is out, its rays paint a grate on the floor, lighting up bright oranges against the squares of worn floorboards. We have so many oranges now! A huge pail full plus a bucket! We also have a lot of pears. And a box of apples and kiwi and a pile of cheese. The metal shelves on the wall are buckling beneath the weight of all the cakes.

Continued on March 29, 2012:

Today is Naked Thursday. Inmates must go out into the hallway wrapped only in sheets or bathrobes and line up so that the doctor can examine each of them in turn, looking for bodily injuries. Cell #210 is different because I live here, so everything that the staff does with us must be recorded on video; the camera is either affixed to the breast pocket of one of the staff or held by hand, but it is always trained on me. For this reason we do not go out into the hallway naked; instead the doctor comes in and makes a notation on a piece of paper, indicating that no injuries were found on any of the bodies. These cameras were a spontaneous and forced invention; they appeared after I had my first visit from the Community Monitoring Commission and complained that I had been treated rudely by the staff. The video recordings are meant to “monitor personnel behavior,” but the camera is always looking in my direction, as though it were not the personnel at all but I who had to be “monitored.” Ugh. I’ll try to make a sketch.

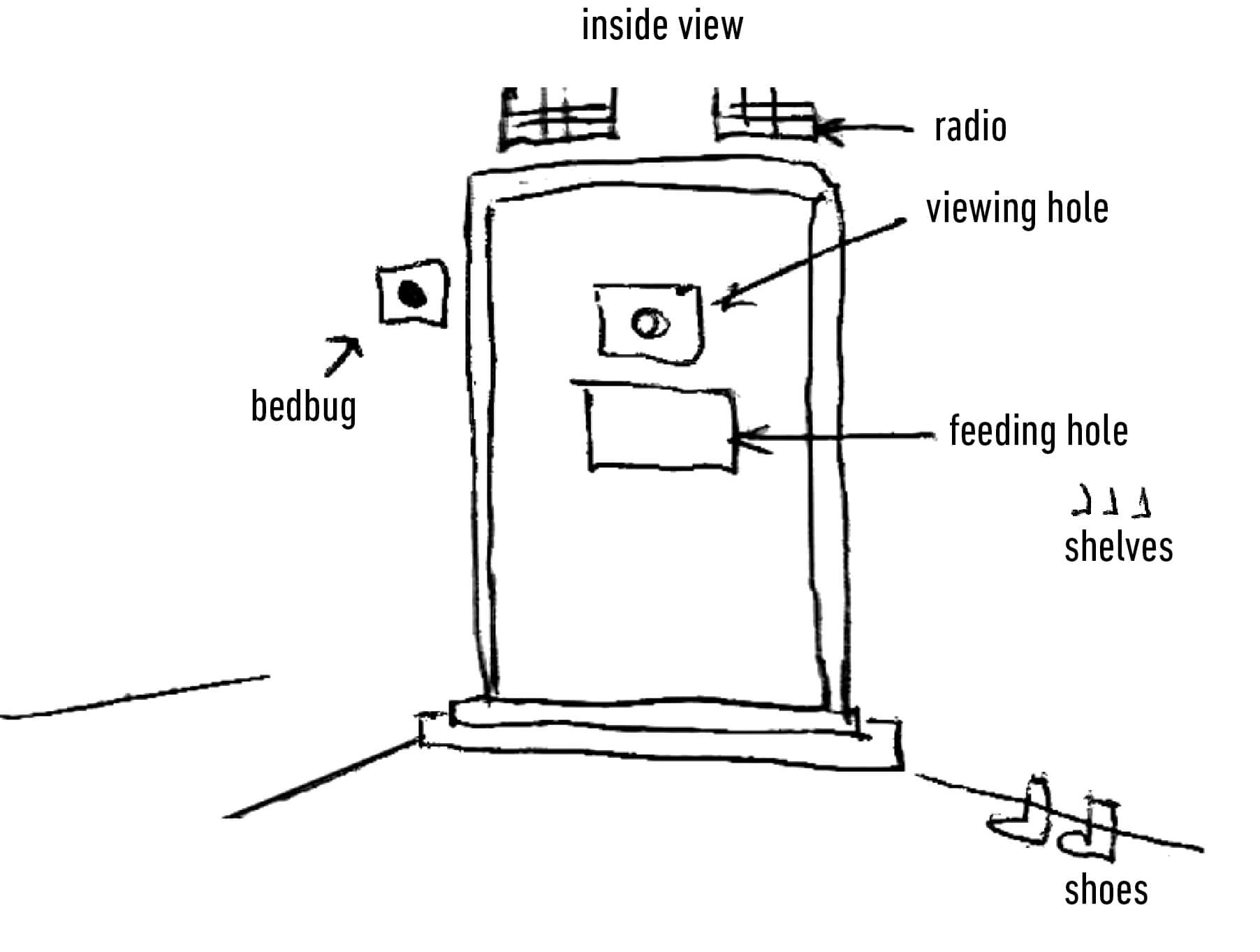

Inmates and staff communicate mostly by means of the feeding hole. Food is delivered three times a day; correspondence is delivered once a day; a scissor knife for cutting bread and vegetables or fruit is also passed through the feeding hole. If you have a question, you have to “squash the bedbug,” which means pressing a well-worn black button that turns on a light that the staff member on duty may see if she happens to be walking through the hallway, in which case she will open the feeding hole and ask, “What you want?” The door is thick and sturdy, made of metal and painted an odd shade of beige. The viewing hole has a curtain on the outside so inmates can’t see what goes on in the hallway while staff members must monitor what goes on inside cells by regularly peeking in.

Olya, I think you know this, but just in case: you cannot put these descriptions up on the Internet or else very bad things will happen to me. Such are the rules of the institution that they can open the feeding hole at any moment to tell me I have 15 minutes to collect my things—and that goes for any of us here. They can transfer me from cell to cell once a week, forcing me to try to adjust to new people every time. A poorly made‑up bed gets you solitary. Keeping letters gets you solitary. And so on. So I was thinking maybe someone else could make drawings according to my descriptions and eventually there would be enough for a show (if there is a need for such a thing). The rules here ban not just paints but pens other than blue (supposedly we could use them to make tattoos—as though we couldn’t make a tattoo with a blue pen). When you write back, tell me whether you want detailed descriptions of everything (but only when you use this mail route—do not say anything about this by e‑mail!).

I was just having lunch and thinking that if I wrote so much about food, I should write about what I do with it now that I have it . . . I make soup. So far I’ve made soup all of one time. This is forbidden, of course, and punishable by solitary, but that’s a small detail. In the common cells, everyone makes soup; it’s more difficult here in the spec [special cells] because the cell is smaller and it’s easier to see what we are up to. I’ll try to make a sketch.

Darn, it doesn’t really look right. Immersion hot-water boilers are dangerous, but I have almost overcome my fear of them. They are allowed here, but only for the purpose of heating—cooking with them is forbidden. I still have not quite figured out at which point heating becomes cooking. So officially we heat up the vegetables in water with oil. But we have to keep mum about it at home.

I don’t know how to continue this letter. Olya. Olya.

Continued on March 30, 2012:

I learned something last night that rendered me unable to write anymore. I’ve told you there are four of us in the special cell. To explain what has happened I will have to go back and write out some details that will allow you to understand it all, I hope. Most of the cells here are “generals,” for 30 people; some are semispecs—for 12 people; and there are specs for 4 people. Living conditions in the specs are considered the best in this institution. I don’t entirely understand how people end up here; some people—and now I think there are many of them—come here after signing a paper promising to work for the administration: to inform on other inmates, in other words. When I was transferred here from a general cell, the three women already in the cell had been “primed”—all of them. They had been told that I had acted as a provocateur in the general cell. This is why it was so difficult for me the first few days here, while they studied me to see whether I was as bad as they’d been told. What’s worse, whenever I was taken out of the cell to meet with my lawyer or the detective, they were called in and told that I had gone to inform on them, that I was claiming that they were mean and bullying to me. And then we became friends and gradually I started learning all this bad stuff, and understanding what filthy, low approaches some staff members use in the work.

That was all prologue. There are three of us in the cell now because one girl has been transferred to a general. When I became friends with the other two women in the cell, this girl quietly wrote a request to be transferred, and once she was out, she gave me up. She reported that I had letters—your letters—which I had secretly brought to the cell, and said bad things about me. That I turned the other women against her and that now the whole cell is saying blasphemous things all the time and she supposedly can’t stand to listen to all that. All night last night I couldn’t believe it. When they were talking about this girl, I had been the only one who said she was good. I stood up for her, you see? I am sorry, this probably makes for uninteresting reading, Olya, but I just can’t seem to come to terms with what’s happened. Anyway, now you have learned a couple more things about this place. I am going to do all I can to make sure you get this letter, but I will no longer be able to take your response back to my cell with me: it’s too dangerous. I am going to read it in my lawyer’s presence and try to memorize it, so please do not forget to write. And please forgive me if I forgot to write about something or didn’t have time to write it. This quotidian filth has prevented me from writing much about what I have been thinking. On the other hand, I just wrote a big article about some of that, and I hope to be able to get it out of here, and then you will read it. Thank you again for everything, all of it. Please stick together, you guys. I hope to see you soon.

Maria

The drawings are reproduced from Maria Alyokhina’s actual drawings. Her labels were originally in Russian. The American publisher has typeset and substituted them in English.

Excerpted from Words Will Break Cement: The Passion of Pussy Riot by Masha Gessen, published 2014; reprinted by permission of Riverhead Books.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.