Books

Moms Are Still Getting a Raw Deal

In her new book ‘All Joy and No Fun,’ Jennifer Senior says working moms are still bearing most of the child-rearing burdens.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

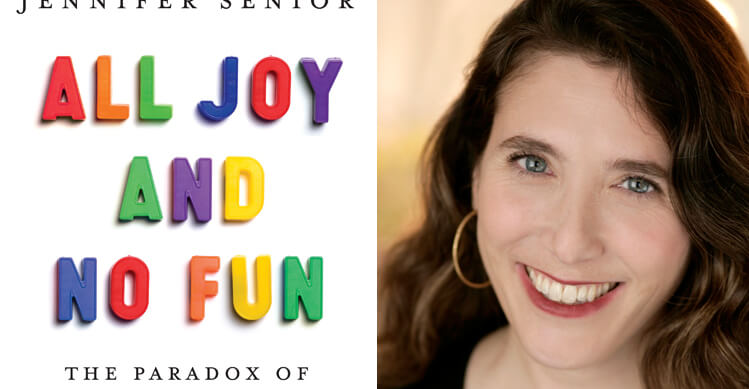

There are plenty of books that address, you might even say, police the way parents are raising their children: from the sensationalistic (Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother) to the whimsical (Bringing Up Bébé) to the instructional (What to Expect When You’re Expecting. But a new book by New York magazine writer Jennifer Senior, All Joy and No Fun: The Paradox of Modern Parenthood, concerns itself less with how to parent and instead turns its attention to how it feels to be one.

And one of the more interesting findings, though not such a surprising one: We expect so much more of mothers than we do of fathers. Once kids enter the picture, new parents’ domestic workload expands more than in generations past, and the typical middle-class mom succumbs to a sexist division of labor, even now, in the 21st century. According to Senior, “Women, on average … devote nearly twice as much time to ‘family care’” than men do. Though men and women may work about the same number of paid hours per day on average, middle-class moms take on a larger part of the childcare workload. In fact, when researchers took a closer look at the childcare data for dual-earner couples with babies, they found that “women were three times more likely than men to report interrupted sleep if they had a child at home under the age of one.” And while that’s been true since before The Feminine Mystique, modern familyhood now requires less of children and more of their parents.

With all the talk of stay-at-home dads and breadwinner moms, you’d think that gender roles have shifted in the modern American middle-class household. Alas, as much as women have made strides in the workforce, there haven’t been parallel strides in the home. Like Jim and Pam on the last season of The Office, the needs of working dads get pushed to the forefront while working moms are forced to pick up the slack in the household.

What’s just as frustrating is that dads often don’t realize how little they’re chipping in when it comes to child rearing. Here’s where the misandrist in me kicks in: Middle-class dads think that they take on about 42 percent of the childcare. But really, their efforts actually measure about 35 percent. That is, dads may think that they do an equal amount of labor: taking out the garbage or mowing the lawn. But it’s childcare, not housework, that exhausts parents the most. As one mother said in the book, “The dishes don’t talk back to you.” This disparity threatens to break up new parents: “If a married mother believes that childcare is unfairly divided in the house,” writes Senior, “this injustice is more likely to affect her marital happiness than a perceived imbalance in, say vacuuming, by a full standard deviation.” She continues, “The division of family labor is the largest source of postpartum conflict.”

Moreover, when dads do take on childcare, it’s the more enjoyable, “interactive” kind. Senior points out that middle-class dads tend not to do routine tasks like toothbrushing and feeding; rather, they’re more likely to engage in, say, a game of catch. For moms, parenthood is not a lovely montage of playing with one’s kids but instead a flurry of time-sensitive domestic tasks: getting the kids ready for school, dropping them off, picking them up, shuttling them to extracurriculars, and getting dinner ready on time. “Fathers … feel no more rushed than men without children,” says Senior. So it seems like we’re stuck in a troubling gender binary where dads do what they want, while moms do everything else.

And because moms spend so much more time with their kids, they become de facto enforcers. Says Senior, “In a fairly recent sample of nearly 3,200 parents of 10- to 18-year-olds, a disproportionate share of mothers said that the task of discipline fell to them alone (31 percent, versus just 9 percent of the dads). Mothers also reported setting more limits for their adolescents: They were 10 percent more likely than dads to set limits on video and computer games; 11 percent more likely to set limits on what types of activities they did online; and 5 percent more likely to regulate how many hours of television their kids could watch per day.” This uneven attention to discipline means that mom becomes the bad guy whereas dad becomes the buddy.

So not only does mom do more work—and more routine work—but her extra labor often goes unacknowledged by her partner and her children. And everyone regards mom as a buzzkill rather than the more attentive and overextended caregiver that she is.

As much as modern American parenthood can be a joy, it is also deeply problematic because of this outsized burden. And the blame doesn’t fall only on men (although, step it up, fellas). It’s also the social structure and economics associated with raising a kid these days. Unlike a couple of generations ago, children don’t contribute to the family economy. Instead, they remain passive recipients of the fruits of their parents’ labor: Raising one middle-class kid costs about $300,000, not including college tuition. These huge financial burdens—which of course weigh more heavily on low-income parents and a great deal of single parents—mean that middle-class parents are so busy keeping their heads above water that they don’t have time to, say, try to subvert gender roles. Senior asks, quite astutely: “Does the state have an obligation or moral imperative to help out mothers and fathers?”

Balancing the childcare load starts at home but requires change at a structural level. Countries like France, the Netherlands, Belgium, and the nations in Scandinavia provide subsidized childcare for parents. Says demography professor Arnstein Aassve, “In general, the happiness that people derive from parenthood is positively associated with availability of childcare.” And in the aforementioned nations, “where childcare is available for children between the ages of 1 and 3 … mothers are consistently happier than nonmothers.”

If you take a closer look at modern American parenting, you’ll see how the lack of a strong social safety net has hurt parents in general and moms in particular. Dads need to step up their childcare game for sure. But when it comes to the enormous work and cost of having kids, maybe Bringing Up Bébé isn’t such a bad idea.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.