Street harassment of black women by black men has become so inevitable, it didn't occur to many that it was something to be dealt with.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

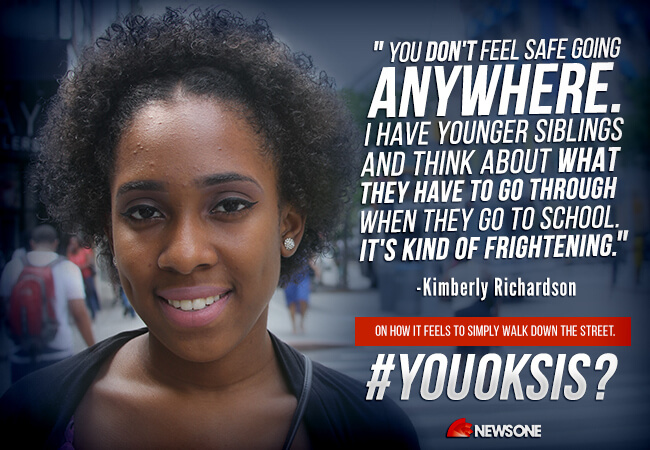

Last week, blogger and Twitter persona Feminista Jones launched the hashtag #YouOKSis? in an effort to create a platform for women, black women in particular, to share their experiences and frustrations regarding street harassment. Not surprisingly, the hashtag thread turned caustic and divisive within the first hour; a few black men felt targeted and some white women felt excluded.

And so yet again, we have to ask, is the hashtag—that undeveloped thought held hostage by a ransom note of mashed-together words—a tool for real activism, or are you just asking for the inevitable criticism, flurry of scorn and well, attention? And does it actually matter?

I didn’t learn about street harassment growing up in rural New Hampshire—in large part, because we didn’t have streets, per se. Not so much as roads and lanes and loops and ways—many of them dirt and quiet, where you could walk for half mile stretches without seeing another house or person, for that matter. And if a boy or man in town ever did say something unsolicited to me about how I looked, I always received it eagerly, because the boy or man was invariably white, and what his attraction to me meant (as I interpreted his inappropriately sexualized comment), was that my brown skin difference was acceptable, even pretty, and not ugly or other or repugnant.

It wasn’t until I visited Boston for the first time that I began to understand what it meant to be catcalled—and it was black men who demonstrated the behavior to me.

I was probably 12 or 13 years old—a year or so after I’d reunited with my birthmother, who is white, and who lived on the New Hampshire seacoast about 65 miles east of the town where I was growing up as an adopted black child in a white family. As a kid, I loved all things urban, especially style and fashion related, as evidenced by the torn out pages from the New York Times Magazine plastered on my bedroom walls, along with posters of Grace Jones and Adam Ant. I dreamt of New York City, but knew that Boston was likely the next best thing and most realistic to visit at least until I got older, so when my birthmother asked if I’d like to make the trip with her, I was excited.

We started at Boston Common, where my birthmother first met my birthfather while he was playing guitar to anyone (women) who would stop to listen (white women). As we walked along the Tremont Street, we approached youngish black men coming toward us walking from the opposite direction. There was no subtlety in their immediate objectification of me—a child—as they openly jeered and whistled and said, “Hey little mama, you look good! Mmmhmmm!” My birthmother ignored them and hustled us along, later telling me that they were just a bunch of “jive black men” who were bored and unsophisticated.

It didn’t feel like that to me. I was unprepared for what it would feel like to have black men look at me, to actually see me—because it had never happened before. I had seen Morgan Freeman’s Easy Reader on The Electric Company, and although I liked to imagine he could see me through the television set, of course he could not. So when these black men looked at me, despite their catcalls and public debasement of a young girl, it felt not like authorization to be considered attractive, as it had from white men, but rather, like a rite of passage.

For years after I would willfully misconstrue catcalling and street harassment from black men as a sort of code speak for black validation and kinship. After college, when I moved to Boston, I used to walk past this one black barbershop in the South End on the way to my internship at the film and television company Blackside Productions. The men who cut heads there would stand out front during down time, button-up shirts and clean sneakers, smoking Newports, occasionally pushing the shoulder of another, playing around trying to start something. As soon as they saw me coming their focus shifted from each other to me; their postures suddenly loose, aggressive, haughty. And then the comments would start to fly.

I was embarrassed at first, then thrilled, then finally smitten, and ended up dating the crew’s ringleader for several months. The whole time we were together he was verbally abusive, dismissive, demanding, and on occasion, used a little too much physical force when trying to make a point. Essentially, he was exactly who he was in front of that barbershop when I walked by every day, but had refused to recognize.

He and his friends had said the same kinds of things to me that prompted Feminista Jones to start the hashtag #YouOKSis?: “When can I hit that?” and “You look thick, girl.” “Hey sexy!” These were comments that were slowly chipping away at my self-esteem, rather than lifting me up in the kindred admiration of black men. In truth, I was not OK, Sis. Because as a woman, I knew better, but as a black woman who had spent my entire early life longing for the company of black people, I didn’t care. I was willing to make that sacrifice.

I understand why the #YouOKSis? hashtag might feel like an attack to some black men—but I also know that when I was indulging sexist behavior, it was because I wanted to give those black men the benefit of the doubt. I wanted them, specifically my boyfriend, to be better, do better. And he didn’t step up. In not calling him out, I was actually doing both him and myself a disservice. It’s not and never OK to make a woman feel unsafe, sexualized, objectified and/or intimidated in public.

Whether for women like me, who were at one time or are now unwilling to recognize the mutual harm as the result of street harassment out of a compromised sense of cultural loyalty, or women who, like “Chloe” and hundreds of other women in the thread tweeted, street harassment had become so inevitable, it didn’t even occur that it was something to be dealt with—if #YouOKSis is helping to shift the perspective, I’m here for it. And yes, it matters. If white women feel excluded, I can’t help you—your individual or group feelings about issues that affect us all is not my work to do. And if black men feel attacked because of it, I love you, but get grown.

The bodies of black women have long been devalued, ostracized, utilized, stolen in this society. I think the point is we will let you know whether or when we want your appraisal moving forward.