Their new remix collaboration is not exactly feminist. But maybe that isn't the point.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

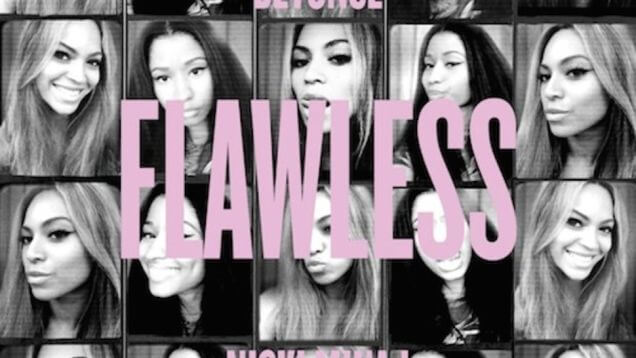

Like many people, I was minding my own business Saturday night, just trying to live my life right, when Beyoncé dropped the “***Flawless Remix” featuring Nicki Minaj that registered a 10 on Twitter’s Richter scale.

From Beyoncé addressing Jay Z and Solange’s Met Gala “Elevator-Gate” (Of course sometime shit go down when it’s a billion dollars on an elevator) to Minaj’s insta-classic, opening line (Like MJ doctor they killin’ me) the bass-heavy, no-holds-barred track revels in its very existence.

The Queen of Rap and Queen Bey? Fahgettaboutit.

They knew the Barbz- and Beyhive-lined streets were hungry for it and they delivered.

While there will undoubtedly be heated discussions about the feminism of Minaj and Beyoncé (or lack thereof depending on where you land on the issue) for days to come, I’d rather discuss how Minaj and Beyoncé are seemingly, in the words of bell hooks, “selling hot pu**y” and what it means for Black women when we unapologetically locate our power within our sexuality.

By serving “delicious pu**y” to “every hood ni**a” who fantasizes about that “pound cake,” it is not a question of whether or not Beyoncé and Minaj are performing for the male gaze—or rather performing for women who perform their sexuality for the male gaze. The question is whether or not that can ever truly be empowering, specifically for Black women in the United States, even if paired with immense personal wealth.

To paraphrase the words of poet Warsan Shire, some men in corporatized hip-hop will split a woman in half searching for their manhood between her legs. And in “***Flawless,” both Minaj and Beyoncé deny those “lookin’ a**” men that opportunity. Yet in this song and others before it, their replication of misogyny in hip-hop is extremely problematic.

There is nothing empowering about calling other women “stupid hoes” or screaming “bow down, bitches,” just as there was nothing empowering about Jay Z rapping about “Money, Cash, Hoes” back in 1998. At least, there’s not supposed to be.

But here’s the thing: Hip-hop is often about aggression, competition, power, and sex.

It is capable of being Id music, a primal sieve through which we drain all of our frustration, joy, desire, anger, and frantic energy. As is most art, hip-hop is not always about being right; it is often about simply being—in all of our contradictions and messiness and humanness. Just as this can hold true for men, it can be equally true for women.

This is not to say that Minaj and Beyoncé are exempt from critical examination, or that people who do so are mired in respectability politics, as is often the charge.

The genetic memory of some Black folks is deep and wide and dark. From slave-auction blocks to the dehumanizing treatment of Sarah Baartman, a South African woman labeled a “freak” by European men because of her large buttocks, to contemporary pop culture, there have not been many spaces where Black, female bodies are not fetishized, degraded, brutalized, and shamed.

That said, hesitancy to embrace unabashed displays of raw, unfiltered sexuality often has less to do with conforming to hypocritical, racialized double standards of respectability, and more to do with the concern over the commodification of Black, female bodies. After generations of being beaten, raped, and tossed in chains or aside as trash, it is difficult for some Black Americans to accept the possibility of Black women wresting control away from and subverting a white supremacist, capitalist, cis-heteropatriarchy that has held our sexuality hostage.

We have never had the privilege of a pedestal.

It stands to reason, then, that compounded with the cultural Columbusing of the likes of Miley Cyrus, Katy Perry, and Iggy Azalea, it can be exhausting defending ourselves against the very same hypersexual tropes that Beyoncé and Nicki Minaj subjectively embody.

Let’s be clear: This thing is complicated and the deeper we dig, the harder the work becomes.

For some Black American women, there is ingrained guilt attached to exploring our sexuality and unapologetically claiming that which we were told was ours to neither define nor enjoy. That is not the case with Nicki Minaj and Beyoncé. They are giving voice to their sexuality. They own it. They are front-and-center, crashing the good ole boys club and throwing their chips on the table. Now, whether that is a good or bad thing all depends on perspective.

Frankly, I don’t need to like Beyoncé or Nicki Minaj. But I need to live in a world where women don’t have to care about who likes them or be penalized for who doesn’t.

So what did I hear when I turned my speakers up to 100 percent Saturday night with pretty much the rest of the world?

Definitely not the late-summer anthem that many people seem to have heard, but the unrestricted freedom and buoyant relief of two bold, Black women with not a single, solitary f*ck left to give.

That, and that alone, is flawless.