The news cycle is an endless stream of horror: stories of domestic violence, police brutality, viral breakouts. Don't think your kids aren't taking it all in.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

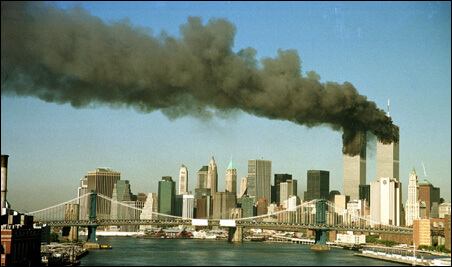

How much have you told your kids about Ebola? About the recent NFL controversies surrounding domestic violence and child abuse? About police brutality, school shootings, beheadings? This question hit a lot of us last week, as we marked the 13th anniversary of the events of September 11, 2001.

I kept wondering why this year’s anniversary seemed to be extra meaningful. Then I realized that my son, now 8, is the same age as his sister was that day (she’s 21 now). My kids being so far apart often lends a sort of “Groundhog Day” quality to my life as a mother: Everything I do with my son, I did 13 years ago with my daughter. Sometimes that’s mundane or even dispiriting—I’ve been packing a lunchbox every school day for two decades and it feels like it’ll never end—but at other times, my situation produces a useful kind of déjà vu.

There’s a lot I don’t know about how my daughter experienced September 11 (her father and I shared custody, and she was at his place that week), but I know she was sent home early from school and learned about the attacks from a school bus driver. What I do remember is how she reacted three years later, when our hometown Red Sox were in the World Series and a ceremonial fighter jet flyover marked the opening home game. They roared right over our house, rattling the dishes in the dining room hutch. She came running out of her bedroom, screaming and shaking. “Are we under attack again?”

It’s no question that my daughter’s generation—today’s college students—were deeply affected by September 11. It was the inescapable bad news of their childhood. But younger kids, too, are coming of age in a post-9/11 world, one marked by warfare, terrorism, and a 24-7 digital media landscape that even adults find overwhelming. What I wonder is how, and how much, to protect them from today’s bad news, and yesterday’s, and tomorrow’s.

The expert advice is pretty clear: be as open with your kids as you can, follow their lead, keep your answers honest and age-appropriate, and listen more than you talk. One nice round-up of these points can be found on the website of the 9/11 memorial organization (click here and then download the PDF); note, though, that the site provides a museum guide for children 8 and up only.

But what real parents do is all over the map. When Adam Lanza went on a shooting spree at Sandy Hook School in Newtown, Connecticut, my friend Laurel told her two sons about it; they were the same age as many of the children who had been killed. “There’s no predicting what will scare a kid,” she told me when I asked her about it. “A kid can know all about Rwanda, but be freaked out by a muppet. So my instinct is to say that we can only open the lines of communication, let a kid know we’re there to help, to talk, to explain. And then let go of the steering wheel. My kids, at 7 and 8, know about Newtown, about the Holocaust, about Jack the Ripper. I don’t turn off NPR. But when, on occasion, one of my boys gets freaked out and asks that I turn off NPR, or change the subject, I do so without question. I feel like my job as a mom is to teach them to suss out what they can handle, and to avoid what they can’t.”

Another friend, with four kids from 8 to 15, says that her approach varies by age. “With the olders, it’s different, but with my younger kids, I tend to take my cue from one of my favorite movie lines ever,” then goes on to quote Laura Linney from You Can Count on Me: “He’s gonna find out that the world is a horrible place and that people suck soon enough, and without any help from you!”

Some terrifying things affect us all, albeit perhaps at a distance: climate change, terrorism, gun violence. Others are more specific: In our family, because my son is black, I’m particularly worried about how he’ll hear about the situation in Ferguson, Missouri, and how he’ll take in the history of police violence against black men in our country. In the end, we didn’t sit down and watch anything about it; as the summer unfolded he heard a few things, and we saw a few instances of police chasing down and (in one case) handcuffing a black motorist. As his white parent, I felt like my job was mostly to acknowledge what he was seeing, to affirm to what he observed, and not offer excuses. I’ve talked with friends whose kids may find themselves or their families at risk because of racism, anti-Semitism, or homophobia, and they all say the same: Protecting your kid from the news doesn’t mean they’re protected from the hatred. So it makes sense to be as open as possible, while reassuring them.

Bear in mind, though, no matter what strategy you go with, random other kids may upend it—your best-laid plans to have a serious talk about 9/11 may be upended by a conversation among second-graders during tether ball, which you’ll learn about when your kid comes home and tells you what some expert named Seth or Sadie said about Osama bin Laden. At the same time, if you opt to be relatively frank with your child, be prepared for another parent to be upset that your kid spilled the beans about something from which they’d hoped to protect theirs.

These issues have been around forever. My brother vividly remembers being terrified watching the television coverage of the 1972 Olympics in Munich, when masked gunmen kidnapped and then murdered 11 Israeli athletes and coaches. “I couldn’t sleep and thought they were coming for us next,” he tells me now; he was six at the time. Unlike most kids today, we watched a lot of TV without any adult company or context. Thankfully, a few years later he got what he needed—what all our kids need—from a babysitter. “I can’t remember what she said,” he told me, “but she was reassuring and made me feel safe.”