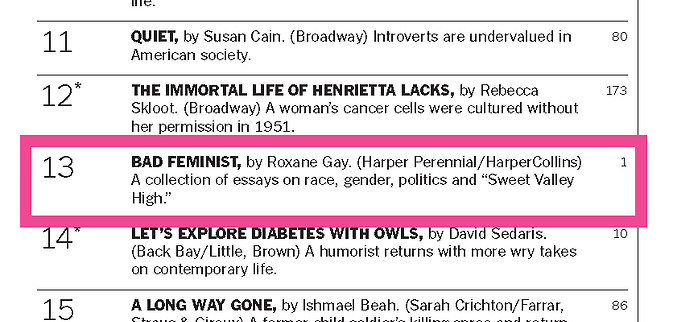

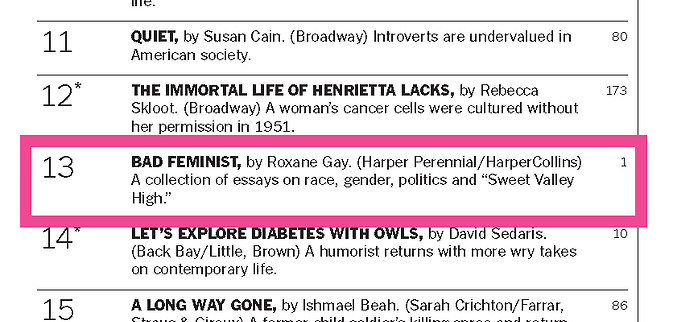

Gay’s book ‘Bad Feminist’ debuted at No. 13 on the New York Times’ best-seller list.

All the Rage

Gay’s book ‘Bad Feminist’ debuted at No. 13 on the New York Times’ best-seller list.

How a “Bad Feminist” Inspired Me to Become a Better One

While reading Roxane Gay's personal essays, the writer had an epiphany: Women telling their own stories is more than just cathartic. It changes the whole conversation.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Jess Zimmerman is our”All the Rage” columnist this week. Kate Harding will return next week.

A week ago, New York Times best-selling essayist and acclaimed novelist Roxane Gay said I was hot. That’s not the point of this piece, but because it’s only been a week, I’m not remotely done bragging. In fact, I made her write it in my book for posterity.

I’ve known Roxane for a while online (we read Naomi Wolf’s Vagina together a few years ago, and we read it FOR FILTH), but her recent Brooklyn reading was the first time we’d met in person. I thought she was exactly how she comes across in her essays: funny, unapologetic, warm with a steely core. And, as I may have mentioned: She thought I was hot.

But again, that’s not the actual point I wanted to make. This is: After the event I started reading Bad Feminist, a remarkable book of essays, in which Roxane deftly aligns her personal reminiscences alongside observations on culture so that the resonances expose a deeper truth. As I read the essays, I started thinking about my experiences and their cultural context in a more artful, cohesive, pointed way. When I finished it, I began drafting personal essays I never would have thought myself capable of. I normally write a lot of opinion pieces, but the kind of open-hearted personal disclosure that Roxane displays in Bad Feminist is hard for me to approach; I worry that it’s self-obsessive. Seeing how Roxane handles it makes it clear that you can use personal stories, even difficult ones, in a way that is both generous and enlightening. It literally made me think differently about my own history, to start arranging it into illuminating patterns.

We talk sometimes about the representation of women’s voices as though it’s an end in itself—as though it’s about fairness. But feminists don’t just want to see equal numbers of women on the National Book Award shortlist or the New York Times masthead for the sake of scorekeeping. Representation is important because listening to other women talk about their experiences helps us recontextualize our own. Sometimes that means we see patterns that give us a better understanding of ourselves—or at least a better way to write about it. But it can be even more revolutionary.

Part of what patriarchy means is that men set the narrative. This can be dangerous; the man-approved narratives about rape and abuse keep women silent and self-blaming and ashamed. It can be insidious, because when a story is unchallenged it’s hard to distinguish it from truth. And it is often self-feeding, because when men set the cultural tone, women’s stories and concerns get sidelined as “unimportant.” The patriarchy has an investment in keeping it this way. Once we can talk to each other, we can compare notes. And once we can compare notes, it becomes a lot harder to pull the wool over our eyes.

This week, a young woman told Buzzfeed News that YouTube star Sam Pepper had raped her in 2013, when she was 18 years old. She hadn’t come forward earlier, she said, because “I thought it was my fault”—Pepper had offered to get her into a concert, and she had willingly gone to his hotel room to “hang out.” The male-dominated narrative she’d internalized told her she had invited the assault by being alone with him, or by not fighting hard enough. But Pepper has recently been the subject of other assault allegations, starting with a video where he groped women on the street as a “prank.” Hearing from other women who’d had similar experiences made the young woman from Toronto reevaluate the story she’d been telling herself. “When I found out that he did it to other people,” she said, “it felt like a sock in the face.”

It’s not just assault and abuse that we recontextualize. There’s been, for instance, a recent spate of articles about women with ambivalent feelings toward motherhood. Hearing other women speak up about their uncertainties—worrying that they wouldn’t be good mothers, facing the sadness of not wanting a child, realizing they’re actually happier with their dogs, wondering whether they already had kids and if so where did they put them—creates an alternative to the dominant narrative, the one in which all “normal” women aspire to joyful motherhood. This conversation has been out there, but usually in unpopular and isolated essays (Ayelet Waldman is still getting snarky asides in the New York Times, nearly a decade after writing that she was more in love with her husband than her children) and jaundiced investigations into whether women can “have it all.” But the growing groundswell of women’s voices is starting to establish another conversation, one in which more of us can find our place. Now that we can hear from other women, we can see that the range of “normal” feelings about motherhood is much broader than the patriarchy would have you believe.

The male-dominated narrative doesn’t have to tell you the truth about whether rape is your fault, or whether you’re allowed to not want children. Nor does it have to tell you the truth about what kinds of things women are good at, about who and how we love, about what qualifies as “beautiful” and what must be done to achieve it. (Here’s where my “Roxane called me hot” bragging becomes more than a throwaway joke. Patriarchal culture tells us one story about what “beauty” means. Expanding the conversation makes it clear what a narrow range this represents.) It doesn’t have to tell you the truth because, until recently, nobody was contradicting it. Now, increasingly, we are. That’s why a lot of “literary men” sneer at female writers: It’s a desperate attempt to defend their sole power to control the conversation. The patriarchy is an abuser: It wants to isolate you from your friends.

Equal representation of women in our magazines, newspapers, and best-seller lists is important because it’s fair, yes. But it’s also important because, as women start to speak up, we complicate the dominant narrative. Maybe hearing from other women gives you permission to finally forgive yourself for something you thought was your fault, or grieve about something that was done to you. Maybe it makes you realize that your goals for your life don’t make you abnormal—that, in fact, you’re in good company. Or maybe, as with my experience reading Roxane, you gain something smaller and yet still profound: a new reading of our personal stories as something cohesive and worthwhile. Either way, it’s no wonder women writers have a lot of men running scared.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.