An abortion made this former Hasidic woman pro-choice. Now living in Texas, where only 7 clinics remain, she’s able to shed light on what it feels like to believe your body is not your own.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

I had an abortion when I was a covered woman in a fundamentalist community. I live in Texas.

I thought about that recently when U.S. Judge Lee Yeakel struck down key parts of a new state law obviously designed to shut Texas’s abortion clinics.* I thought about it back when the law was enacted, and when the clinics all over the state were closed because of it. I wonder why no one seems willing to admit they’re doing this in the name of God.

But obviously religion has everything to do with it.

When I lived among the Hasidim, the Jewish ultra-orthodox, we thought religious Law was the same as morality, an echo of God’s booming voice, so that our any breach left us naked and filthy before Him. After I left them, I was dismayed to find, out here in secular world, yet another group of male voices I didn’t know nodding sagely while legislating intimacies about my body “for my well being.” It seems a lot of people think the law should echo their particular God.

As Hasidic women, we had to wear dresses that covered our knees and elbows and collarbones. We tried for a noble modest bearing, since we were constantly told we carried within ourselves the Future of Our People. With birth control forbidden, sex could always result in a child, whose soul entered at the moment of conception. That soul would be marked, or damaged as a birth defect, by our modesty and by the depth of our devotion.

God owned my body—not me. His Law ensured I kept myself thoroughly covered, my voice low in public. There were large volumes governing my clothing and behavior and my sex life in great detail.

I gave birth to seven children in ten years. The children were my world. I would have given up anything to protect them.

If I were to get in my car today outside of my Houston home and head straight toward California, after 13 freeway hours I’d reach the halfway point—tumbleweeds, dry flat land, wind farms—and still be in Texas. Across that vast space the two abortion clinics that survived the new law are slated to be closed.

One of every ten U.S. births is in Texas. The state covers 268,820 square miles. Before the new law, there were 44 such clinics in the whole state. Nineteen remain. If it weren’t for Judge Yeakel, a Bush appointee, there would be even fewer.

But they shouldn’t be called abortion clinics. Many of the closed clinics were women’s health-care clinics, often the only affordable source of pap smears, mammograms, birth control … and abortions.

Most of the people in our community were Republicans—when they voted. Each week, families and friends gathered around a Sabbath table laden with dishes of homemade food and home-baked challah bread. It wasn’t uncommon to hear political talk there. Right-wing politics and religion melded together as they tend to do, although privately I always thought Conservative Christians strange bedfellows.

Then as now, abortion was a flashpoint. I would shake my head in wonder at the undisciplined selfishness of those women who indulged at whim and then discarded the consequences at public clinics. I tried to imagine lines of women at those clinics, but I couldn’t think of them as real. My children were fully alive to me the moment I knew I was pregnant, and my children defined my life. How could those women …?

When I found I was pregnant again for the seventh time, my body rebelled. Most evenings during that pregnancy, I lay on the sofa using hand gestures to communicate as the children swirled around me. Then the doctor induced a premature birth, and I fell into the waves of labor and blood and pain and tiny cries. But I had trained myself to submit. I’d trained myself so well.

One night after the birth of our three-pound son, the doctor put me at the end of her rounds and pulled a chair close to my bed where I lay in modest gown and headscarf. “Leah, it’s time,” she said. She’d meant it was time for me to stop, time for me to take control, time to protect myself from the Law. No more babies.

I laughed. “You don’t understand,” I said. This is our Law, our life, and it’s all older and wiser and bigger than me. I don’t get to say who I am. Our Law is who I am. Which doesn’t explain the new tiny voice coming from me, convincing my husband that we had to start using birth control.

Of course it would remain a secret. But over the next two months, I was amazed that I could have sex without fear, sex without feeling exhausted just thinking of possible consequences, sex without guilty pleasure. I could have days in my busy mothering life that weren’t simply an interim between pregnancies, and didn’t have to keep myself mentally prepared for another round of infant care. I dreamed my body was a new house I now owned and I had stolen the key.

And yet, I was mired in an awful mix of new conviction and old fear of judgment, which is probably what led me to forget the diaphragm one night. I knew almost immediately that I was pregnant. The next day—racing pulse, eyes darting—my body was flush with adrenalin, trying to run away from itself. A body scream.

Last year, the first after the new Texas laws, there were over 9,000 fewer abortions in our state. Texas media seems to particularly enjoy interviewing female representatives of Christian and anti-abortion organizations crowing success.

But I imagine 9,000 women in that body scream. I imagine amateur self-abortions, marathon drives into other states, women who don’t have the money to make the drive mulling desperate measures to get it. I imagine thousands of newborns whose mothers don’t want them or can’t handle raising them.

Knowing the great lengths I would have to go to get an abortion did not change the body scream. I knew at a visceral level that the pregnancy could kill me. Now some wild woman had stepped apart from obedient selfless religious me and was whispering the outrageous immoral murderous “A” word in my mind.

I tried to reason with her. Through housework and cooking and childcare, I talked to her. I prayed. I looked in the mirror and tried to recognize who I had become. But this pregnancy wasn’t a child to me. It was more like a cancer.

I pictured those women at public clinics, but now I saw real people with real needs for survival, intimacy, health, and love. I saw myself standing among them, frantic, holding my breath and feeling the growing threat inside me.

Our two youngest children were 15 months and a 3-month-old preemie, the oldest a 10-year-old with special needs. If I died, I was sure my children would be scattered—their father couldn’t possibly both work and care for them. Now it seemed not having an abortion was a far more certain way to increase the number of throwaways.

I thought, It’s my body and my spirit at risk here. This is not for the government to decide. This is between me and God.

Now, since the new law, ghost women and their babies, some alive, some dead, follow me. I wonder who will care for these mothers, this rash of babies? The Texas legislature hasn’t offered a parallel increase of funding to Women and Infant Children, foster care, public health clinics, or mental-health services.

It took everything I had to tell my husband what I had to do. Then I watched shock and horror pass over his face. I fully expected him to say he would divorce me. I would lose my children. My community would reject me. I had nowhere else to go.

He shouted. He called me a murderer. Then he walked away, turned his back, and cried.

I knew that Jewish Law allows an abortion if the mother could die. In my timid voice, I asked the doctor to tell our rabbi that another birth would kill me. But she refused to say there was an outright threat, since I had suffered exhaustion, not a heart condition. Perhaps, I said, she could imply …?

That was going to have to do.

How I remember the rabbi’s accented voice on the phone that day telling us, “Okay, you have to do this.”

“This?” I said, but he wouldn’t say the “A” word.

In that moment when the rabbi pronounced our baby’s fate, we were children before him. We had allowed him, had asked him, thus managing to skirt the greatest most terrible responsibility of our adult lives.

I blinked, realizing this. But we had always deferred such decisions to our parental Law and rabbis. I thought, we have never even attempted a mature relationship with God. I wanted to murmur, we didn’t know.

But I had a new voice, one that had audaciously convinced a doctor to help me subvert our Law. I opened my mouth to cry out that this was my decision. Just then the rabbi added,

“And do not speak of this to anyone.”

Because of the rabbi’s ruling, I had a secret abortion without losing my home and family, my friends and community, my marriage or financial support. My husband took me for the surgery, tucked me in bed at home afterwards, fed and bathed and bedded down the children, and, ever the obedient soldier, never spoke a word of his grief and loss that became an arid field between us.

After the abortion, everything—and nothing—was the same. I remained a covered woman in that life for several more years. But I had spoken up. I had overruled our religion and taken control over my body. I knew I would never again allow anyone to make such decisions for me.

It seems it takes a certain amount of freedom from law to get to fully inhabit adulthood. I was left keenly attuned to law that robs us of self-agency, law that, in the guise of protecting people, attempts to be the voice of someone else’s God.

Today I wonder: Can’t our legislators hear the silenced desperation they’ve created like a wildfire across our state?

We had no more babies. And I, with a story I couldn’t speak and a raw new voice like some Pandora escapee, late one night as my family slept around me, well, I began to write.

* On October 2, Judge Yeakel’s ruling was overturned, which will immediately close 13 more clinics in Texas. The seven that remain are in major metropolitan areas only, requiring driving as much as 700 miles.

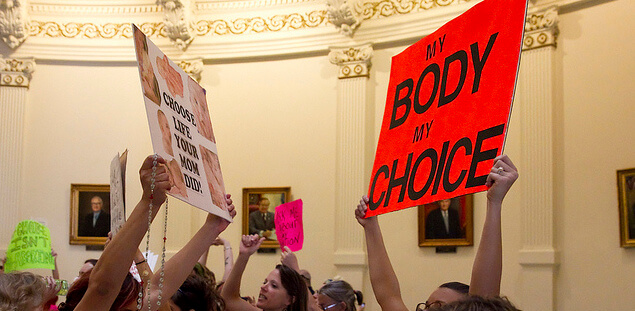

Photo credit: Flickr user The Texas Tribune