J.Law won't be hackers' last victim. As we are increasingly pushed to put our lives online, personal photos are the least of our problems.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

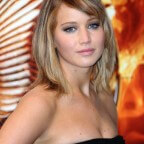

I love me some kick-ass women. Not just because I aspire to their greatness since I’m prone myself to making excuses for other people’s bad behavior, but also because there’s something deeply satisfying in seeing someone rise up against her tormentors. So I was thrilled when Jennifer Lawrence—an Oscar-winning actress whose very personal (yes, nude) photos were stolen by hackers, and exposed to the public—told Vanity Fair how angry she was that her privacy was violated. “It’s my body, and it should be my choice, and the fact that it is not my choice is absolutely disgusting. I can’t believe that we even live in that kind of world.”

She didn’t say she was embarrassed. She did, however, rightly call the incident a “sex crime,” and took umbrage at those who felt free to take a peek themselves, adding, “Anybody who looked at those pictures, you’re perpetuating a sexual offense. You should cower with shame. Even people who I know and love say, ‘Oh, yeah, I looked at the pictures.’ I don’t want to get mad, but at the same time I’m thinking, I didn’t tell you that you could look at my naked body.”

And though I wish she didn’t feel the need to clarify that she was in a “loving, healthy, great relationship” when she took them—it really doesn’t matter for whom the pictures were intended and in what context they were taken, whether a one-night stand or long-distance love or sexy marriage proposal—her message was still the same: Step off. (As Elaine Lui, another kick-ass woman who runs Lainey Gossip, a smart, insightful celebrity news website, observed, “I worry, for those who were hacked and they weren’t in loving, serious relationships, does it make it any less of a violation? I worry that it only strengthens the belief that a woman who is sexual and is not in a commitment is somehow deserving of scorn.”)

Just because a person makes a living being in the public eye doesn’t mean everything about her life is meant for the public. Respect. But increasingly, those of us who don’t make a living being in the public eye are finding it difficult to hold onto anything private, too.

In 2009, a photographer discovered that photos of her two children she’d been storing on Flickr had been filched and reused on a Brazilian social networking site). Just this summer, a Virginia woman found out that a fellow Instagram user had repurposed photos of her kids into a racist meme. Even those who are supposed to protect us end up exposing us, too. Take the 15-year-old British teen who recently found a bikini photo of herself used in a school assembly, plucked from Facebook by a teacher intent on making a point about the lack of privacy. Oh, the irony.

The debates are often framed two ways: to post or not to post pictures? And are you smart enough to lock down your privacy restrictions? Either way, here’s the translation: Your privacy is completely under your control.

Or is it? In a world where digital images have pretty much replaced prints, and film cameras gone the way of dot-matrix printers (and, soon, all printers, given how we’re constantly being encouraged to save trees and go paper-free), what alternatives do we have? Do I upload my photos to Snapfish and hope they’ll keep them secure? Or should I invest in digital printers—so much for going green—and send hard copies to far-flung friends and relatives, many of whom would prefer to receive them online so they’re not left wondering what to do with these prints once they’ve seen them? (I don’t lay claim to their refrigerator real estate; theirs may be reserved for their children’s artwork or pizza menus.) Where does one even buy photo albums anymore? (And no, I will not scrapbook or buy a handmade one from Etsy. I draw the line.)

It’s not just pictures, either. Banks don’t want us to stand in line for tellers anymore; they urge us to balance our checkbooks by mouse, not by pen. Doctors want us to communicate via health websites—password-protected, they remind us—where they post medical test results and give instructions about prescriptions. (I confess, it’s easier to get responses by email from my internist this way, rather than wait for his call.) My oldest turns in papers via Dropbox; my middle child gets homework assignments by email; my youngest goes to a school that’s recommending yet another social network designed expressly for classrooms—again, password-protected—as a way to receive information about upcoming fund-raisers, school events, and, yes, share pictures.

No matter how constrictive we make our privacy controls, there are endless breaches. The hackers who stole Jennifer Lawrence’s photos share headlines with those who’ve broken down firewalls built by behemoths like Target, Apple, and JP Morgan Chase (which are presumably stronger than my pedestrian home wi-fi network). The most recent infringement affects 83 million businesses and households.

As it happens, October is apparently National Cyber Security Awareness Month. An email arrived in my inbox today exhorting me to “create strong passwords and keep them safe” and to “safeguard” my personal information and “not overshare personal information on social networking sites.” But Jennifer Lawrence wasn’t posting her nude selfies on Facebook. And the millions who bank at Chase weren’t blasting their PINs on Twitter. Just the other day my bank (not Chase) told me my card had been compromised—which they couldn’t explain—and that a new one was on its way to me. Never mind that I’d never used this particular card online, and am the type of person to shield the keyboard anytime I use the bank machine.

Even if we school ourselves about the dangers of conducting our lives online and in the ether, and brace ourselves by amping up our privacy restrictions to “11,” we still have no guarantees that what we deem to be private will remain so. Not our nude selfies, nor our text-message spats nor the $52 that will have to tide us over till the next paycheck. Nothing feels solely ours anymore. It’s as if we ourselves, not just our pictures or passwords, are as fungible as unfiltered images waiting for the sweep of a Photoshop tool. One trespassing click and we no longer belong to us, but to everyone else, too.