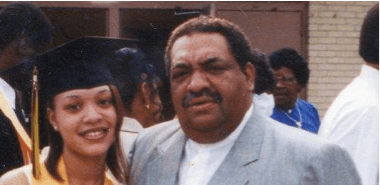

Daughters

When My Dad Died, I Wanted to Die Too

Our columnist couldn’t imagine existing without her best friend and father. Three years after his death, she’s learning how to live with the grief.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

When my father, Theodore “Bubber” West, died on October 18, 2011, I wanted to die.

I’ve never told anyone that before now, but as the third anniversary of his death approaches with agonizing slowness, I feel strong enough to say that if not for being afraid of causing my children the same pain that I felt, I don’t know what I would have done.

When he died, I didn’t recognize myself anymore. So much of my identity was being my father’s daughter and nothing was the same. What was the meaning of life and was it worth it?

These were questions that I could no longer answer as I navigated the world exposed, vulnerable, hovering somewhere above my body between reality and a dream state. Other times, it felt as though I were in a bubble deep beneath the sea. I could see people at a distance, but they couldn’t see me. I could hear words coming from their mouths, but they made no sense.

My father was and remains my hero, my rock, my best friend and a life without him didn’t seem possible. It still doesn’t. How do you put one foot in front of the other when the ground beneath you is crumbling? How do you speak when unshed tears claw at your throat? My heart didn’t feel broken or shattered when my father died. It felt as if it had been ripped bloody and pulsating from my chest, leaving only a gaping hole to remind me of its existence.

I’ve written about him before. But it was when the grief was fresh and raw, and the protective numbness allowed me to focus not only on who he was to me, but to other people: his passion for social justice and political reconciliation; his refusal to bend to popular opinion and teaching me never to follow parties, rather to question and engage ideas. My father was a public servant who gave and gave and gave to his community until he had nothing left to give.

Then he gave some more.

Among other health issues, he had an enlarged heart, which made perfect sense to me. His heart was too big. He trusted too much, loved too hard, and worked tirelessly to make everyone around him happy and the world is darker without him in it.

As fall settles in during this third year since his death, my grief is much more subtle. It’s not this looming monster that threatens to destroy me. It’s a shadow that follows me, a lingering chill in the air even when it’s warm. Grief has become something that I no longer try to fix because, with time, I’ve grown to understand that it never goes away. You just learn to live with it.

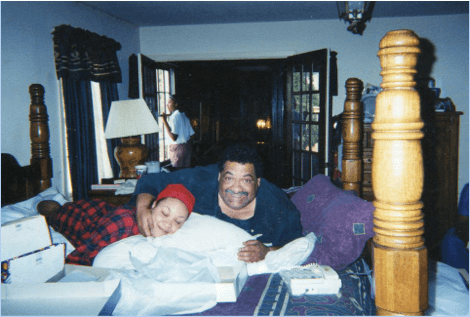

But I miss his hands—wide, callused hands that would rub my back or grab my hand just to kiss the palm and tell me he loved me.

I miss laying across his bed watching a Motown special on television and discussing the “feud” between the Temptations and the Four Tops.

I miss his laugh. Oh, his laugh could light up a room and reverberate for hours after he left. I miss reaching for the phone to call him in the middle of night, just because. I miss the light that came into his eyes whenever I walked into a room, knowing that it reflected the light in my eyes at seeing his face.

I miss seeing him getting dressed for work in the mornings. The familiar scent of his aftershave and cologne wafting through his bathroom as I trudged in blearily to get ready for school, always passing his watch and ring where they sat perched on his nightstand.

I miss cooking with him after my brothers were asleep. I miss going to his office, stopping at the coffee machine just outside his door to make him a cup before walking in—cream, two sugars.

I miss his famous card tricks that he would pull out whenever my friends came over.

I. Miss. Him. And the longer he’s gone, the more at home the hurt becomes.

There are days that I can deal with the pain. When I remember that all he ever wanted for his children was for us to be happy, I realize that nothing would devastate him more than knowing that his death caused even a second of unhappiness.

But it hurts. My two older sons were born before he died, but my youngest son will never know firsthand the depth of his grandfather’s love for him. He will never feel the security of knowing that, other than his parents, there is a man who would move mountains for him. Of course, I can tell him stories, but a story can’t replace the feeling of laying on his chest and feeling his laugh reverberate until a responding smile tickles your lips—and knowing that in that moment, all is right with the world.

He’s always made everything right.

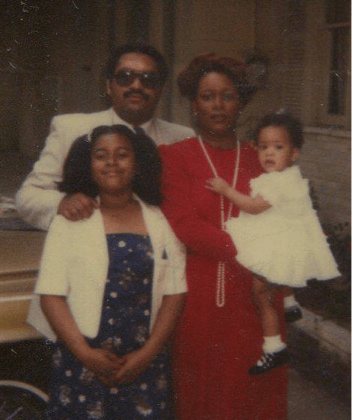

When I was 18 months old, my mother, Jacqueline Rose Smith West, died from a brain aneurysm. It was October 13, 1981, my big sister’s 11th birthday and two months before my mother’s 30th birthday. Monday was the 33rd anniversary of her death.

From the time that he felt I was old enough to discuss it, my father always said that I saved his life. He told me the story of how he had packed me and my sister up and took us to his parents’ house with the intent of dropping us off and going somewhere to heal without reminders everywhere of our mother, his first and one true love.

My grandfather George, who would die from a heart attack three months later in January of 1982, said, “Son, of course your mother and I will keep the girls for you. But let me ask you this: If you run away, will that make Jackie come back?”

“No, sir.”

“If you leave, will you stop hurting?”

“No, sir.”

“Then stay here with your girls.”

And there he stayed. Thirty-one years old and raising two daughters, an 11-year-old and an 18-month-old, on his own. He would eventually remarry and give me two adorable baby brothers, but in those earlier days it was just the three of us. He said that when my sister was asleep, he would allow the tears he’d been holding in all day stream down his face as he talked about my mother and cried it out. He swears that I would look deep into his eyes as if I understood every word. And he laughed when he recalled that I would hit him over the head with my bottle with my juice order—“apple juice, light ice” —exactly how I drink it to this day.

According to my father, two things helped him begin moving through the grieving process.

“I stopped going to the cemetery every day, baby girl. I realized that your mother was in my heart where she’s always been; I didn’t have to go stand at a stone. But before then, I raged at God. ‘How dare you take my Jackie from me?’ I’ve been a good person, how dare you take my wife, my girls’ mother, from me? Why me? Why me?!’

And I heard a voice, baby girl, and it said, ‘Why not you? You work in the funeral business and you see death and grief every day. You see mothers burying daughters, fathers burying sons, sisters burying brothers. Why not you? What makes you so special?’”

Three years after his death, as the murders of countless sons have ripped open the post-racial façade of a nation, as mother after mother, father after father, are forced to bury their babies after they’ve been gunned down by monsters with badges, I remember his words and I ask myself, “Why not you, Kirsten?”

Grief is the price one pays for love. And I am fortunate to have known my father’s love so completely and so intensely, to have him there to walk me down the aisle at my wedding and to see his face at the hospital when I gave birth to my two older sons. I am grateful that he was there to wipe my tears and hold my hand until I was 31 years old.

About a month before my father died, during one of our nightly calls, he told me to move home, back to Mississippi, and I laughed. I had called him from our tiny apartment in downtown Los Angeles and the tears just fell.

“Daddy, it’s so hard. I love to write, but there’s just no money in this. I’m stressed out. I never get to spend time with the boys …”

“Come home, baby girl.”

“Ha! You want me to leave L.A. and bring my entire family back to Mississippi and do what exactly? I can’t do that, Daddy. And you know it. I have to make this happen. I can’t afford to leave.”

About a month later, I would be seeing my father for the first time in nearly two years, laying on the table in a freezing cold mortuary. And it felt like coming home. I held him and didn’t want to let go. I rubbed his hair and traced his face.

“I’m here, Daddy. I’m here, Daddy. I’m here, Daddy. I’m here.”

The guilt was immense. All I could think about were the days when I was preparing to move. He cried as if his heart was breaking and said, “I’ll never see you again.”

I looked at him like he had grown three heads. “Of course you will, Daddy! What are you talking about?”

“I won’t. I won’t.”

It wasn’t until after he died and I spoke with one of his doctors that I discovered he was suffering with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). That is what he was covering up when he wouldn’t allow his doctors to give me information and I was furious.

“Why would he keep that from me?” I cried to one of my uncles. “Why?”

“And what would you have done?” my uncle responded.

“What do you mean, what would I have done?! I would have come home. I would have taken care of him. I would have made sure that he got everything he needed to still be here.”

“And now you know why he didn’t tell you,” my uncle said. “He never wanted to be the cause of you not following your dreams.”

“But it’s still not fair. He shouldn’t have made that choice for me.”

“He didn’t make it for you; he made it for him. He did it his way, as he always has.”

And when the soloist sang Frank Sinatra’s “My Way,” at my father’s funeral, one of his favorite songs, it brought the house down because his energy moved through that place like lightning.

I shouldn’t be surprised that he died in fall, the season that I feel most alive. His last gift was allowing me to feel him in the breeze, to see him in the burnt oranges and burgundies and golds of autumn leaves and hear his voice in the stillness just when I need it the most.

The last three years were spent learning to live without him. The next three will be spent learning to live for both us. Just as he would have wanted.

*I love you, Daddy. I’ll always be your girl.*

Click here to learn more about COPD.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.