Beauty

Relax, Minister, It’s Just Mascara!

The cosmetics-loving writer reminisces about her feminist awakening after a humiliating day in church, as she reveals the true story of Jezebel, the Bible’s most famous "harlot."

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

I was home from college one weekend, 35 years ago, attending church with my family in southern Indiana when our minister launched into a tirade. Not even a “Good morning, congregation” did he offer before he started in: “Brethren, Satan has been allowed a foothold in this church, and it’s women who are leading the church away from God with their makeup!”

What provoked this? I was stunned.

“Women, it’s because of YOU that Jesus cannot return! Your makeup … is-an-abomination! Throw it out!” he screamed, as if my Bonne Bell lip gloss were a bomb ready to detonate.

Amid the complete and total silence a woman quietly cried.

The minister cited verses in the Bible that forbade the use of makeup. Most notably was the story of King Ahab’s wife, Jezebel, who painted her eyes, had God’s prophets murdered, and was accused of “harlotry.” For her sins, Jezebel came to a very unpleasant end. Both King Ahab and their heir apparent were dead, and the incumbent king Jehu was approaching. So Jezebel styled her hair, painted her eyes, sat at the window of the royal palace, and contemptuously asked Jehu if he came in peace. Jehu ordered Jezebel’s eunuchs to throw her out the window, and Jezebel’s corpse was eaten by wild dogs.

According to the Fundamentalist church I was raised in, Jezebel was the epitome of everything a good, compliant, modest, obedient Christian girl should not be: She was a harlot, and she wore makeup. It seemed as if those two qualities were interchangeable.

“And why,” the minister concluded, “do you women think you can improve on God’s work?”

I knew I could. I had pale skin and eyelashes and eyebrows so blond they were almost white. Makeup wasn’t a luxury. It was a necessity. Without mascara, eyebrow pencil, eyeliner, lipstick, and a little blush, I resembled a white mouse with blue eyes. Not the kind of look with which a woman wanted to face a judgmental world. What right did the church have to put its paws on my body? I was fuming. I could feel stirrings of feminism within me for the first time, and with it, a quest for the truth, and not the truth that the male leaders of the church were passing off as gospel.

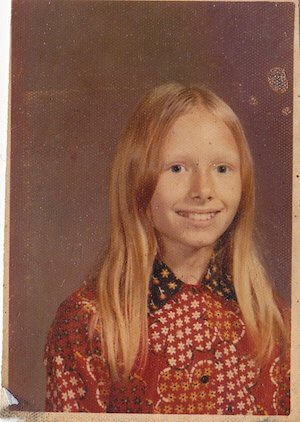

The author as a young girl.

I left Indiana 34 years ago, and now live in New York City where I possess a formidable stash of mascara. I was reminded of Jezebel’s story when I went to the Metropolitan Museum to see the “Assyria to Iberia at the Dawn of the Classical Age” exhibit (which runs through January 4) and saw a small, square ivory carving of a woman’s face peering out the window. Her plucked brows arch over almond-shaped eyes that are rimmed in kohl. Her hair is curly and thick, falling to right below her chin. Who was she intended to represent? Perhaps Astharoth or another one of the goddesses that were worshipped by the Phoenicians or other people who lived in the Levant, in modern day Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq.

The woman’s face in the ivory reminds me of proud, defiant Jezebel, hair arranged and eyes made up, sitting at her window and awaiting her fate.

Jezebel ruled for 30 years with King Ahab during the 9th century BCE, and theirs was a formidable political alliance, allying her father the King of Tyre (modern-day Lebanon), with Ahab, king of the Northern Kingdom of Israel. During their reign, the northern kingdom was at the height of its power. According to the Bible, King Ahab’s palace was adorned in ivory, no doubt courtesy of his Phoenician-born princess wife, Jezebel, and ivories discovered in the Israelite royal compound in the capital city of Samaria (perhaps King Ahab’s palace itself), are included in the exhibit.

An ornate 9th-century BCE seal discovered in 1964 bears the name “Jezebel.” Decorated with the goddess Hathor’s crown and a crouching winged sphinx, similar to the sphinxes on the Samarian ivories on exhibit, it’s clear that although she’s been slut-shamed from Samaria to southern Indiana, Jezebel was a woman of status, and was anything but a harlot. Her “harlotry” was idolatry, whoring after other gods, and as Jehu approached, Jezebel’s final action—arranging her hair, making up her eyes, and sitting at the window—might have been meant to signify that she was aligning herself with the goddess, and publicly renouncing Israel’s male god.

Reframing Jezebel, this powerful Phoenician woman, as a prostitute, effectively trivializes her, reducing her to a woman whose only value is sexual. Jezebel was ruthless, yes, but her story has been re-appropriated to serve as a cautionary tale to women who might yearn for power.

I am far removed from Jezebel in time and place, and in temperament. Tempted though I often am, you won’t catch me persecuting today’s religious “prophets.” However, I left my church long ago, and in that small sense, I understand Jezebel’s final message: No man has any business taking away something that is mine, not even in the name of God.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.