Our guest columnist knows first hand that some men with a dark side are incredibly adept at putting their best face forward.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

When a wife stands by a man accused of sexual misconduct, be it adultery on one end of the continuum or rape on the extreme other, the public response is usually laced with a whole lot of “How could she?”

I can tell you how.

When I was college age, I was part of a ragtag group of artists—illustrators, musicians, dancers, writers, the whole megillah. We lived within blocks of one another in adjacent crappy San Francisco neighborhoods, and we shared an open-door policy—if you needed studio space, a place to crash, something to eat, someone to talk to, there was always somewhere to go. Most often, we headed to Tommy’s.

Tommy’s studio loft was sort of our homing ground and Tommy*, hair in a bandanna, paint brush or hammer in hand, was the Gladwellian connector through whom we all met and stayed close. His spare futon was the don’t-think-twice-about-it temporary home for out-of-town visitors and people in between apartments, and he never asked for anything in return. He wasn’t much of a cook, but we often used his kitchen for experiments that we plated on mismatched thrift-store china and passed around. He was always light on his feet, an accomplished long-distance runner, and he rarely slept. I’ll never forget him patiently disassembling my toilet at four in the morning and taking hours to dislodge a monster clog after some genius tried to flush a full pan of kitty litter. He dated one of my closest friends, and he came over all the time, often overnight. He wasn’t controlling or domineering or mean or even occasionally pushy. I’d never heard him mansplain anything. It’s not too much of a stretch to say I loved him as a friend, and I trusted him without a second’s hesitation.

I am always cautious around men, always on the lookout for any lack of respect for boundaries, for sexual opportunism. Safe to say my creeper-radar is pretty well attuned. So when I tell you that Tommy was the last person I ever would have expected to be a sexual assailant, I mean it.

Then, a decade or so later, came the phone call …

My friend who had dated Tommy sounded strange, her voice quiet and shaky. “You know that guy that we’d been hearing about who was secretly filming those women in the changing room at xxxxxxxxx?”

I shifted in my seat. “Yeah?”

“It’s Tommy.”

There was a very minor ripple of news media about the discovery. A woman who had suspected Tommy set a trap to catch him in the act and photographic evidence was produced. His face was plainly visible in the photos. There was no denying it was him.

“Lily, be honest with me,” my friend pleaded. “The whole time you knew him, when we were going out, did you ever suspect…?”

“No,” I said. And I meant it.

I wish I’d never had to learn how much inner strength it takes to accept that someone isn’t at all who you thought he is. That he is frightening, capable of violating women. Over and over. Inside of someone you know, a monster lurks. To keep those two people separate is impossible, but merging them together, knowing that they’re one man, your friend, felt impossible, too. The feeling wasn’t like the clawing, blown-apart “I need to know everything” pain of discovering a lover’s infidelity, or the collective can’t-look-away shock and horror of 9/11, or even the blood-freezing “the terror is unfolding before me” fright of Jack Nicholson recoiling from the rotting bathtub lady in The Shining. Instead, I felt a loopy, lightheaded, stoned-on-cold-medicine remove. The world seemed almost funny in its unknowability. The feeling I literally could not believe it was happening. The air felt thinner, everything shimmering as if it were a mirage. What I knew to be safe and reliable wasn’t. This wasn’t the guy that I knew. This wasn’t my world anymore. Adrienne Rich said it best in her classic book, “On Lies, Secrets, and Silence: “When we discover that someone we trusted can be trusted no longer, it forces us to reexamine the universe, to question the whole instinct and concept of trust. For a while, we are thrust back onto some bleak, jutting ledge, in a dark pierced by sheets of fire, swept by sheets of rain, in a world before kinship, or naming, or tenderness exist; we are brought close to formlessness.”

I walked around in a daze for about a week after I found out about Tommy, unable to integrate this new reality, the old reality fractured but still so very alive in my memories. Was it denial? Dissociation? Things felt elliptical and intimidating. Nothing made sense or felt real. I tried to land on a verdict about Tommy—he’s horrible. He’s my friend. He’s monstrous. He treated me with kindness and respect and generosity. I carried the unnerving realization that someone who was so much a part of my life was now someone I would, almost certainly, never feel comfortable with again. And I couldn’t ever know a person completely. One of the nicest guys I knew was doing the awful things. Scumbag, scumbag, scumbag. My friend, my friend, my friend.

Reading the statements from Cosby’s 38-year-old daughter, Evin, I understood her steadfast affirmation of support for him. “He is the FATHER you thought you knew. The Cosby Show was my today’s TV reality show,” she wrote. “Thank you. That’s all I would like to say (she added a smiley emoticon).” The goodness of her father is real to her. I understand her impulse to showcase the sunny side of her father. That a darker side may very well exist doesn’t mean that his dedication and devotion to her do not.

“Do I contradict myself? Very well, then I contradict myself, I am large, I contain multitudes,” said Walt Whitman, a statement on human nature that can both console and terrify. As I learned with Tommy, and as Cosby’s wife and family may themselves have to accept, there are some scary-ass multitudes out there. Sex offenders are not all red Solo cup-toting frat boys or stubbly, knife-wielding thugs lurking in dark alleys or pasty guys in white vans slowly circling the block near the playground. They move among us, some hidden behind an image of guilelessness and, in Cosby’s case, boundless paternal bonhomie and wisdom.

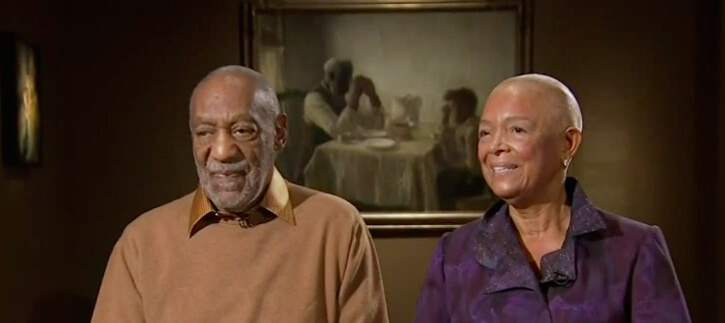

The statement by Cosby’s wife Camille is more elaborate than her daughter’s, yet similar in its buttressing of her husband’s character.

“I met my husband, Bill Cosby, in 1963, and we were married in 1964. The man I met, and fell in love with, and whom I continue to love, is the man you all knew through his work. He is a kind man, a generous man, a funny man, and a wonderful husband, father and friend. He is the man you thought you knew. “A different man has been portrayed in the media over the last two months. It is the portrait of a man I do not know…”

The duality of human nature seems a simple construct on the page or the screen, but when faced with it in your own life, heart and mind, the paradox is maddening. Impossible to hold. This person I love and trust, on whom I depend, is capable of despicable things? Does not compute.

As the Cosby story further unfolds, I keep thinking about Camille and Bill’s children, how they’re faring, what they’re thinking and feeling, how they shape their days. Inevitably, I find myself humming this song from the musical Showboat to myself: “Oh, I can’t explain/It’s surely not his brain/That makes me thrill./I love him because he’s, I don’t know,/Because he’s just my Bill.”

The truth is a razor, not an eraser. Truth slices things open and apart, cuts them down into pieces. It can wound deeply as well as liberate. Yet as it clarifies, it often complicates. The monster hidden from view may be revealed, yet you can’t forget the kindness or the good. I learned this with Tommy. I haven’t seen him in years. He’s done horrible, horrible things. But he’s still my friend.

*Certain identifying details have been changed.

Lily Burana is our guest columnist.