How is today's America betraying Dr. King's dream?

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

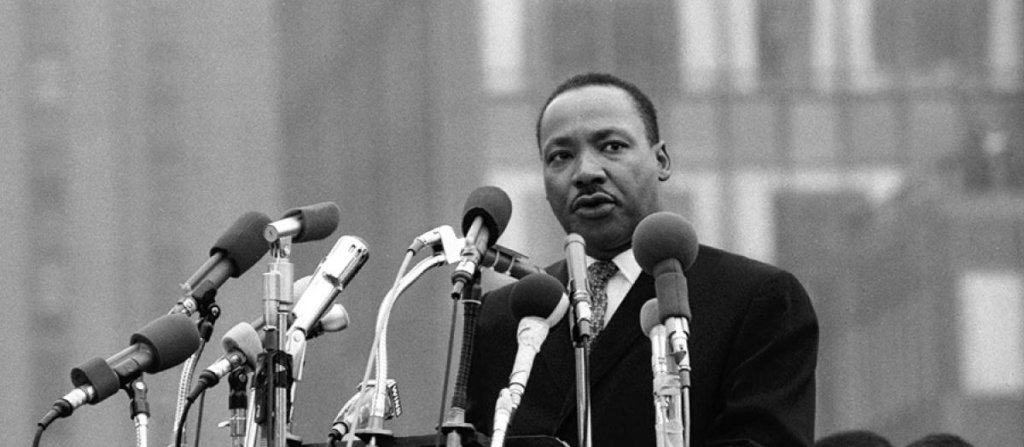

It’s been over 50 years since Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech, and as we’ve been reminded over and over again, that dream is far from being realized.

From Michael Brown to Eric Garner—and too many names to recount that came before and have since followed—we are continually reminded that the nightmares of American racism have never gone away. And that Dr. King’s words resonate even louder today, especially those words that will be forgotten as our nation pauses to commemorate his legacy:

“I am convinced that if we are to get on the right side of the world revolution, we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society,” King said in a 1967 speech. “When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.”

This past summer we saw what happened when we failed to heed Dr. King’s warnings, to make the necessary changes, with tanks and military-grade weaponry, the continued building of prisons across the nation—which are more common than job-training programs and educational opportunities for all children—to the entrenched realities of America’s war on terror.

Here, in America, the mainstream media focused its attention, and therefore ours, on the shooting victims at Charlie Hebdo in Paris—and Americans channeled all of their outrage and grief there. And yet there was no media attention or public outcry against two types of terrorism targeting Black people: the bombing of an NAACP office in Colorado Springs, Colorado, on January 6, and the ongoing attacks of the Boko Haram group in Nigeria, that burned more than 3,700 buildings and brutally slaughtered some 2,000 civilians, mostly women, children, and elderly people. Our news is curated for us, and the terrorism story America was going to get on the front page was Charlie Hebdo—if ever you needed further proof that this country socializes its citizens to care more about White lives than Black lives.

The American media, the government, and as a result, most of us ignored the other two atrocities to declare solidarity, “#JeSuisCharlie”—or, as I call it, the French version of #WhiteLivesMatter—in response to the murders of a dozen staffers and several other bystanders at the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, whose stock in trade was making fun of different religions, and in particular, mocking the Prophet Muhammad on its cover. The attacks on Charlie Hebdo for disrespecting the Prophet Muhammad were met by righteous indignation from the American and European mainstream media. Please don’t misconstrue what I am about to say, because I, in no way, condone the taking of lives, but it seems as if the defenders of the Charlie Hebdo cartoonists expected the extremists to sit down over a falafel and discuss the finer points of satire to settle things. The killings escalated the frenzied examination of whose speech is free, the limits and impact of so-called satirical comedy, and the fact that dozens of world leaders put their leadership duties on hold (much like New York City did when the Brooklyn cops were killed) to march in Paris to decry attacks on free speech. And this demonstrates the power of the narrative and how it plays out for people of different colors and cultures in real life.

The language of satire and “free speech” provides a cover for racism and it allows powerful and ordinary White people to enjoy the dehumanization of people of color. This enjoyment, expressed in various forms, attempts to obfuscate the genocidal potential of White supremacy. We saw this during Jim Crow when the U.S produced racist films, songs, lynching, and comical postcards, and other consumer goods making fun of Black people. These items circulated in the context of segregation and lynching and they drew from a deep well of racist ideas about Black people’s bodies, brains, sexuality, and character to argue that they were unfit for modernity and full citizenship rights.

That’s what comes to my mind when I see Charlie Hebdo’s satirical magazine covers, one of which features the young girls kidnapped by Boko Haram, hands on their pregnant bellies, crying for their right to welfare benefits. A similar racist image, a postcard produced in the early 20th century in the United States, also shows a pregnant black girl child with her dress strap suggestively dropping from her shoulder. Though produced at different times and worlds apart, these mass-produced pictures play on racial ideas about black children and sexuality. France and the United States have a long heritage of trafficking this kind of racist smut under the guise of humor.

Defenders of Charlie Hebdo claim that this brand of satire is a way of poking fun at the privileged and the powerful. But I ask: How do you make fun of the powerful by using racist images of the marginalized and oppressed?

And we see the consequences of how racial dehumanization is central to the project of White supremacy. As millions marched silently in France to mourn the victims of the horrific terrorist attack, Nigeria was burning and many wondered where the public outcry and gathering of leaders was over 2,000 massacred Black bodies, as well as reports of two 10-year-old Nigerian girls being used as suicide bombers in attacks on Nigerian markets.

The issue is not only about whose speech is free, and whose voices are heard, but when Black lives matter. Do Black lives matter when jokes are told and the diversity boxes are being checked, but not when lives are on the line, when voices are shouting pain and rage? Do the voice and words of King matter when they are used to reaffirm the fantasy of post-racialism and not when his piercing critiques slay White supremacy from sea to shining sea?

Whether in hard news or entertainment, the common theme and message of these global incidents is the popular notion that people of color have no agency and cannot be empowered to take control over their own destiny, speak for themselves or speak up for their rights. The shared message is that White lives matter, that White voices matter, and that White humanity is the only humanity worth protecting and respecting. The efforts from White America’s historical gatekeepers and the White benefactors of the Academy to silence Ava DuVernay have made this all too clear.

There was a backlash against the film Selma, because director Ava DuVernay recounted the story of the very real struggle for Black folks to vote from a Black perspective, and chose not to portray President Lyndon Baines Johnson as the prototypical White savior. Some White critics have slammed the film’s depiction of LBJ as inaccurate, which may be why DuVernay was overlooked for a best director Oscar nomination.

The criticism directed at Selma encapsulates the idea that people of color have no agency and cannot be empowered to speak for or on behalf of themselves, or empowered to take control over the telling of their histories. How dare DuVernay, a Black woman, create a film about America’s shameful racial past, de-center White folks, and produce no White heroes to save the day?

When DuVernay took the radical step of placing the actions and perspectives of Black people at the forefront of the civil-rights movement that changed our nation’s laws, White historians not only criticized the portrayal of LBJ as “inaccurate,” but The Jewish Daily Forward, for example, argued that Selma disfigured the historical civil-rights movement by “airbrushing” Jewish allies from the film even though in reality Selma was driven largely Black activists. The daughter of the famed rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, who marched alongside King, said she was “shocked and upset” by the exclusion of her father from the movie. While a handful of people spoke out against Selma, there were many more bloggers and people on social media who have been supportive of the film. Unfortunately, the critics were effective. I am not equating the White historians’ criticisms of the portrayal of LBJ with Jewish allies and rabbis not being included in the film. There were, in fact, many strong alliances and collaborations with Jewish individuals and organizations, most prominently in the NAACP and the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. This is an important point because it speaks to the much larger issue of diversity in all Hollywood movies and television and how far we have to go to be truly representative and inclusive. I must note, however, that its seems that it is mostly Black people are criticized for this by other groups.

There has never been a time where we’ve needed a movie like Selma more, especially during the emergence of the #BlackLivesMatter movement, as we continue to grieve and be outraged over the non-indictments of cops who have been killing unarmed Black people on a near weekly basis; the ensuing debacle and controversies over the killed Brooklyn cops, and the atrocious and damaging antics of the NYPD publicly disrespecting Mayor Bill de Blasio and his interracial family.

I was in tears watching Selma. I cried because we are still on that bridge, being beaten, bloodied, disrespected, and disregarded in our quest for our rights in this nation.

We are still fighting the Republican-led state legislatures’ sustained assault on voting rights with voter ID requirements, voter list purges, voter registration restrictions, and other rules that are creating barriers for people of color, the young, the elderly, and the poor to exercise a constitutionally protected freedom: the right to vote. In Selma, Black people fought and died for the right to vote. Decades later, racists are trying to take it away again. The sense of frustration and futility is enough to lay a people low with trauma fatigue and the last faint flickers of hope because White supremacy is a beast that keeps changing form, as the complexion of this nation rapidly turns brown.

Seeing Selma gave me an even greater appreciation for the blood, sweat, and sacrifices made by my people so that I could enjoy a fundamental right of American citizenship – the right to vote. As Black people were on the Edmund Pettus Bridge on “Bloody Sunday,” March 7, 1965, getting brutalized, I couldn’t help but think back to all the tear gas and tanks unleashed on Black folks in Ferguson. You have to keep asking: How much progress have we really made?

As I watched the film, I was so emotionally raw that I felt like I wasn’t wearing skin. I saw Black people in the theater turning their heads away from the opening scene, as four girls were blown up inside the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963. They turned away from other scenes of ruthless White violence against Black people. I cried. They cried.

I wondered what the White people sitting in the theater were thinking and feeling. At the end of the film all the Black people rushed out while Whites stayed glued to their seats in silence. Were those Whites in the audience genuinely interested in facing this shameful history? Were they too in agreement with the critics of the film, or were they aghast, in shock, devastated?

The criticisms of Selma, from the theater box-office sales to the Oscar ballot, tell us is that we are still fighting over MLK’s legacy and who gets to tell the story of pivotal moments in American history. We’re still battling over whose voice gets heard, whose speech qualifies as hate speech, whose voice get attacked or silenced altogether, and who gets to die with sanctuary.

We have to give major props to the power of social media, which has been a major force in elevating the voices of Black intellectuals and exposing White supremacy in new ways. It has been used to put pressure on mainstream media to give prominent coverage of the Boko Haram kidnapping of the school girls, to the shooting of Mike Brown. Most recently, activists Twitter-shamed mainstream media to cover the NAACP bombing coverage. And Facebook and Twitter has been used to galvanize and mobilize people in this day and age to strive for basic civil rights and other forms of social justice.

I can’t help but wonder what King would think and say about recent events that make it torturously clear that the truths and lives of people of color in America and elsewhere don’t matter. I can’t help but wonder how he would be responding to a culture of violence and erasure. Would he be demanding media attention for the violence in Nigeria, questioning the role of U.S. militarism in the ongoing destruction of Black lives there?

Can you imagine King tweeting #BlackLivesMatter, #JeSuisCharlie, #NAACPBomb, or #IAmNigeria? Or would he, along with Ella Baker and Fannie Lou Hamer, protesting the lack of diversity within Hollywood, onscreen and during the awards show—tweet with hashtags “#OscarsSoWhite”?

Surely, he would be at the forefront of movements challenging the unfulfilled dream that #BlackLivesMatter. He would surely ask the nation what does it mean if Black lives have no value other than to serve as sources of humor and to legitimize White supremacy, which is especially painful and ironic as our nation pauses to celebrate Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

Whether on the Edmund Pettis Bridge, a forgotten village in Nigeria, or the streets of Paris, the message is resoundingly clear and consistent. White supremacy is alive and well and it is expressing itself through militarized policing and the killings of unarmed Black people, divestment in communities of color, foreign policies and military campaigns, and standing in solidarity with its European sister which is audaciously and defiantly fighting to preserve its right to dehumanize and engage in cultural terrorism against Muslims under the cover of satire.

No amount of historic revision or reciting of King speeches changes that reality. Yet, the struggle continues—on the streets of Ferguson and New York City, on highways and in malls. No amount criticism of tactics or tones will stop the wave of agitation, a tsunami building toward radical change. King’s wisdom remains; it can be seen in the work of organizations like the Dream Defenders, Millennial Activists and Black Youth 100; it can be seen in #BlackLivesMatter and protest signs. It can be seen on social media where hashtags provide a powerful tool for instantly raising awareness, galvanizing attention, focusing emotion, conveying outrage and standing up against that stubborn old harridan White supremacy.