The honeymoon may be over for this writer and her husband. But, inspired by the resiliency of her parents’ union, they rediscover their love for each other in unexpected places.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

“Every marriage is pregnant with divorce.” —Brian Doyle, “Irreconcilable Dissonance”

I like to imagine my parents during their newlywed days, my mind a grainy filmstrip, navigating their new partnership. My father used to hide my mother’s cigarettes before he went to work in the morning. He’d leave a note: “Where are your cigarettes? Are they in the freezer?” Mom, showered and ready with coffee, would look in the freezer and find a second note: “Could they be in the bedroom somewhere?”

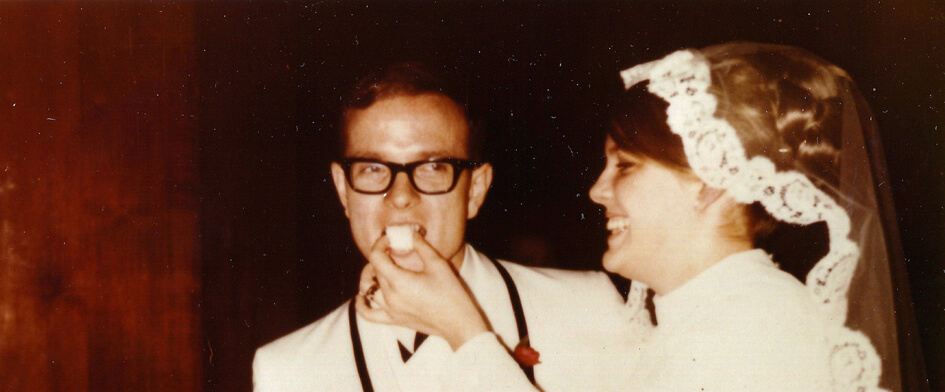

And I love to look at photographs in leather-bound albums. Mom with her young updo, Dad with his brown 1970s slacks and perpetual moustache. Hair vibrant. Eyes unlined. Their smiles infectious. They’ve been together for over 40 years. As we age, as time tricks our faces with such imperceptible changes; we are forever further from who we once were, and yet so little seems to be changing.

Surrounded by cardboard boxes, I’m unpacking. I find a box of photographs and rescue the stained-glass mosaic frame—our wedding picture. Instead of a traditional image of bride and groom at the altar, the picture is dark. We’re almost silhouetted against a wall of neon lights. In the forefront, David is smiling. He’s wearing his class-A uniform with a paratrooper’s maroon beret, and his eyes are closed. My lips kiss his left cheek. My dress is hidden beneath a ratty cardigan, my hair is in ringlets, a sprig of baby’s breath behind my ear, and like his, my eyes are closed. We eloped to Vegas during a dreary February. On short notice, our closest friends and family flew out to celebrate with us. My father, a thrifty man who’d been telling me to elope my whole life, was elated when we made the spontaneous decision. My brother took this picture. It was meant to be joke, a family laugh at one particularly ridiculous wedding announcement photograph we’d received the previous summer. But I love it.

This is our eighth apartment in our fourth city in our seventh year of marriage. With each move, David champions frugality and weightlessness. Some old part of his former Army self beckons and he advocates the liberation of living out of a footlocker. Although we don’t own much, we love books. And we can’t seem to part with any of them. Each move is exhausting. This time, I’m unpacking the bulk of our belongings by myself while David stays in Michigan where there is work for paramedics.

My mom once told me about the time she and Dad broke up. He’d bailed, and their courtship was over. Then, months later, Dad got sick. Mom heard about it through the grapevine and visited him. After his moment of fragility, they rediscovered a stronger union. She always ends the story with a nod in my direction, or my brother’s, “It’s a good thing, huh?”

When they’d just started dating, Mom had a “one-too-many” moment. She’d come home from work and set her hair in curlers while her roommate made cocktails. “There was probably this much Coke,” Mom tells the story, holding her thumb and index finger a centimeter apart, “and this much whiskey,” thumb and finger stretched as far apart as possible. She’d danced around the apartment with her headphones on, travelling through the rooms singing full-voiced into a hairbrush: a graceless, music-less karaoke. Before their date even started, she ended up on her knees in front of the toilet, stringy vomit dangling from her lips, while my dad held her hair back for her, shouting, “Spit! Spit! Don’t you know how to spit?”

He’s full of good advice. Mom tells me that whenever they’d get down about money or work, he’d pull her in and say, “We got the world by its ass, honey.” And he meant it. They had everything they needed.

Another of the countless boxes. I find my journals and stack them neatly on bookshelves. I rediscover our old journal, a hand-bound notebook I bought in Chicago, during our dating days when we lived 800 miles apart. The pages are filled with letters to each other. In it, there are confessions we’d made after arguments, promises and poems. It’s a collage of our courtship and early marriage. My favorite entry is one of David’s, written long before we were engaged: I share your bed and lay awake for hours. The light from the window is blue—I decide that heaven must be blue.

When we were dating, David lived in North Carolina, stationed at Fort Bragg, and I lived in a converted attic apartment on Chicago’s northwest side. The long distance was a challenge. We were young, both 22. I had just finished my bachelor’s degree and was free to fly down to visit him with the tips I earned at a lucrative cocktail waitress job. But still, after six months, at that point when you’re supposed to be so inseparably in love, so consumed by the need to be close, I started to feel doubt—distance and absence stronger than conviction. Then during one shift, somewhere between Friday and Saturday, the cold of January whipping at the windows, the jukebox quiet and the staff in cleaning mode, the phone at the bar rang and someone called out for me.

David was in West Virginia.

“Can you get your shift covered tonight? I should be there in another ten hours,” he sounded eager, breathless. He was AWOL, and he was on his way to see me.

Something like that gives a girl goosebumps.

When we had been married for about three years, we fell into a funk. After the Army, we moved back to Michigan because we didn’t think much about what else we could do. Somewhere between me finding a job in a cubicle and David cooking at a Coney Island, the excitement of marriage ebbed away and we were left with a sharp boredom.

The framework of a marriage can only sustain a young couple for so long. Neither of us felt compelled to have children, like so many couples turning their attention to babies, so we were just idle, plenty of time and no real direction. Because we were both lost individually—no ideas about our future goals—together, that sense of disorientation was amplified. David declares his own propensity to be dysfunctional. He’s not adept at planning, he’s impulsive, driven, but what is that worth when you don’t know where to go. On the other hand, I’m highly functional—compulsively functional, addicted to functionality.

Many nights, we went walking around the dull suburbia where our apartment complex nestled against countless others. We’d walk away from the stacked housing toward houses. Across the park, up and down dimly lit side streets, peeking in windows. We’d see televisions, casting their flickering glow onto the sidewalks. Cozy, lamp-lit living rooms. Many houses had manicured lawns with landscape lighting. The smells were intoxicating, a blend of whatever was in bloom, cut grass, and food wafting from the late dinners of strangers.

We walked because we didn’t know where we were going. My hospital job was a drain. David had tried on school at the local community college, but he dropped out. The assignments felt artificial, there was no real discourse. He was bored. Eventually, he started painting again. He built a studio in our spare bedroom, amassing oils, Sumi ink, an easel. Then he moved into that studio. He started buying six-packs, then twelve-packs. We were like roommates. I discovered the thrill of video poker, an empty pastime. We co-existed.

But we still walked, and I always liked passing older couples. I imagined that they were retired, that they’d spent a lifetime together. They’d walk slowly, with matching white hair. And even though life felt unbearable to us then, we knew we wanted to get old together.

Because our marriage ceremony was in a Vegas chapel, because we planned the whole thing two weeks before we flew out, we suspended any expectations. Our officiant was provided by the venue, A Chapel by the Courthouse. We didn’t write vows, but we were pleasantly surprised by the words we were invited to speak at the ceremony: I promise to remember what we have left to discover in each other.

That’s the important part, really. Remembering, despite apparent familiarity, that time happens to us all, that change is constant and our lives are forever in a state of flux—even when we can’t perceive those subtle lines and wrinkles.

How does divorce happen? How do two people who’ve committed themselves to each other, their present and their future, give up? Our response to the consequences of life can be fueled by either choices or reactions—mindful consideration or simple fight-flight. I imagine that sometimes divorce is born from reactions, from people changing without discovery, without the patience to explore each other’s newness, without choice.

Eventually, David would earn his paramedic licensure, and I would enroll in a graduate program. We’d move to a university town and go to school together. With some direction, our differing levels of functionality finally started to work together again. Like David always says about his experience in the Army: You remember the good things. Yes, you know that parts of it were terrible, but the memories that stick out are the ones that glow. In our marriage we have lived through tendencies toward depression, through selfishness, but we remember frivolity. We remember spontaneous wrestling matches. Needing to touch toes during a conversation in the garage of new friends and being teased for this behavior. We remember our trips: to Savannah, to the Outer Banks of North Carolina, travels around Michigan. We remember evenings on the deck at my parents’ house—Mom teaching David how to polka, Dad telling stories. We remember all the steps we’ve taken to become a family.

When David was in the Army, an enlisted infantry paratrooper, he had a good rapport with one of his commanding officers. During a lunchtime conversation, David learned that this lieutenant and his wife had never passed gas in front of each other. When David came home from work that night, he told me immediately; we were consumed by the seeming impracticality of this situation. How, after over ten years of marriage, had they avoided this?

Growing up, whenever my dad farted, he’d stomp his foot on the ground, as if killing the culprit that caused the noise. Mom would laugh. My brother and I would laugh, stomping our own awkward kid feet in mimicry and praise of the gesture. Now, when we visit my parents for holidays, or stay with them between our perpetual moves, whenever anyone farts we all stomp our feet. We laugh: Mom, Dad, my brother, David. It’s not so funny anymore, but to stop would be the end of a ritual.

Repacking and unpacking our belongings has become our ritual. The folded tapestries, David’s unframed oil paintings, the expired toiletries tossed into another shoebox. But it’s a joy to rediscover the symbols of our years together. Our combined music collection, a box of incense, a gift from a friend, with just one stick left that we can’t burn away, the hideous potholders Grandma and Aunt Marilyn sent to North Carolina in their post-nuptial “wedding shower in a box.”

We’re a long-distance couple again, but this time I feel no doubt. When I look at photographs, I can see the changes in our faces, but I have to study the images to find evidence of time. And in less than four months, David will be in Minnesota. To situate all the books he’s keeping in Michigan while he works this semester, as well as his guitars and clothes, we’ll relive this ritual together. People will ask us, “How do you do it? How can you live apart like this?” Just like they asked the same questions when we were so young. But when we dive into our ceremony of cardboard boxes and packaging tape, we’ll steal secret moments and touch toes.