Getting tucks, fillers, and Botox has practically become a rite of passage, and yet none of us seems to know the etiquette. Do we say something? Or pretend not to notice?

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

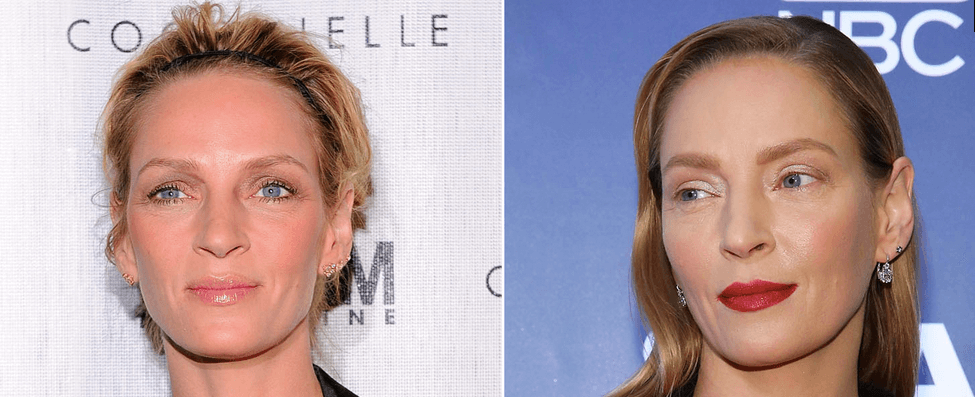

Somewhere between the “Uma Thurman Pulls a Renee Zellweger” and the “Uma Thurman … Wears Minimal Makeup on Red Carpet” headlines is a conversation worth having, one grounded in decency and perhaps old-fashioned protocol.

It’s a conversation I began to think about more than a year ago when I got eyelash extensions. I loved them—they made my short straight lashes a bit more Kardashian—but I felt self-conscious. So when a week after the procedure I ran into my Über-environmentalist friend and she blurted out “Are those lash extensions?,” I stifled a gasp. She’s not allowed to ask that, I thought. “No,” I lied, trying for a mix of amusement and indignation, and adding something about a “really good mascara.”

By the time I got home, my shame was so great that I called my friend and confessed. But I wondered which of us had committed the greater sin: Me for lying about my lash extensions? Or her for asking about them?

Cosmetic enhancement has gone from the domain of celebrities and socialites to, well, the rest of us. The American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery reports that more than 11 million cosmetic procedures, both minimally invasive and surgical, were performed in the United States in 2013. Botox tops the list of non-invasive procedures (up a whopping 700 percent since 2000) while liposuction has edged out breast implants as the most popular surgery. And those figures don’t include such enhancements as lash extensions and teeth whitening, which have become as commonplace as a mani-pedi.

These statistics surprise exactly no-one. Who among us doesn’t indulge, or know friends who do? And yet, despite the ubiquity of the procedures, we remain unsure how to respond when someone calls us out, even with a compliment; or what to say – if anything – when we bump into a friend whose body is no longer quite the same. It might be easy to let fly our opinions about someone as public as Renée Zellweger or Uma Thurman, but when it’s our office mate, our sister-in-law, an acquaintance, or, gulp, ourself, the rules are lot less clear.

Part of the problem is that it’s uncharted territory. Extreme Makeover arrived in our living rooms in 2002, making clear that “normal people could have plastic surgery,” says Beverly Hills–based plastic surgeon Dr. Brent Moelleken. In the years since, procedures have become more advanced, less invasive and more affordable, making it as likely that your waitress is indulging as your lawyer.

Just because more of us are doing it, however, doesn’t mean we’ve become blasé. How—and whether—we enhance our looks is a polarizing issue and navigating the topic has become a minefield. When Hollywood stars such as Kate Winslet establish the Anti-Cosmetic Surgery League and resolve to “never give in,” it can contribute to a cultural sense that there’s something weak about it. Was it any wonder then, that I, who’d cheered every word of Naomi Wolf’s The Beauty Myth, felt conflicted about spending two hours under a bright light while a stranger used surgical glue to give me the lashes of Jessica Rabbit?

But if we’re going to publicly alter our looks, does that mean it’s fair game to call us out? Should polite society look the other way or is it rude not to comment?

Vivian Diller, a psychologist in New York’s Upper East Side, former dancer and model, and author of Face It: What Women Really Feel As Their Looks Change, compares what’s happening now to the era of “does she…or doesn’t she?”, the iconic 1962 Clairol hair dye ad campaign. While Diller’s middle-aged clients feel conflicted about their own—and their friends’—enhancements, the 20-somethings are far more comfortable and open. The day will come, she says, when we treat cosmetic enhancements the same way we currently respond to a friend’s great new highlights.

We’re not there yet, however. After all, “does she or doesn’t she?” has practically become a parlor game, and the gleeful tabloid outing of celebrities’ surgery contributes to an atmosphere of disgrace. Fear of being judged, or appearing judgmental, keeps many of us pretending that a 40-year-old friend’s pillowy lips are the result of a great new gloss. Or that a neighbor’s seamless brow is the consequence of a dedication to juice cleanses and yoga. Or, for instance, that my long lashes were created by a fabulous mascara.

While the issue itself is fraught, the protocol around it doesn’t need to be, says Jodi R.R. Smith, author of The Etiquette Book: A Complete Guide to Modern Manners and president of Mannersmith.com. Smith is adamant that my friend should not have asked. However, if I had brought it up, “then she’d be free to cross-examine.”

Moelleken prepares his patients to expect no response from those who aren’t privy to their procedures. Good surgery, he says, should be undetectable. While most of his patients “want to be under the radar,” there are a few who want to share that they’ve had work done. “They’re un-embarrassable,” he says.

Hope Potter Chavez, a 43-year-old from Albuquerque, New Mexico, “wasn’t embarrassed” about her tummy tuck, posting plans for her surgery on Facebook. A C-section had left her a lumpy scar and she “was doing something positive” to get her body back. She embraced others’ curiosity. “People wanted to know how I was, how it went and how I was recovering.”

A Facebook posting might be a bit too public for many of us. Wynne Dubovoy told only a few close friends about the breast reduction surgery she had around her 50th birthday. When others complimented her – “they kept asking if I’d lost weight”—she responded with a simple thanks.

That’s entirely appropriate, says Smith. “Unless it’s your mother or a police officer, you are not obliged to answer any question you’re asked,” she says.

What about those who don’t subscribe to this etiquette? Who demand to know just what we’ve done and even what it cost? “There is a segment of the population who delights in making people squirm,” says Moelleken. “It’s probably best to admit to a small thing.” Lying, he says, can lead to getting busted.

Ashlie Hawkins disagrees. It’s nobody’s business, says the 32-year-old, who nonetheless blogged about her breast reduction surgery. “Women have to take control over their own bodies,” she says. “That should include not only what they do with their bodies but also what they choose to share about their bodies.” Hawkins’ surgery did “significantly” alter her appearance because, along with the reduction, she essentially got a breast lift, she says, so she anticipated comments…and others’ discomfort. She was happy to put others at ease. “People phrase things in very strange ways when they’re trying to tell you that you look good, and they’re happy for you but what they actually mean is “Hey, your boobs look great.””

Suzanne Hughes, a marriage and family therapist in San Carlos, California, treated herself to Botox after raising her kids. “I wasn’t going to wear a sign saying ‘I got Botox,’” she says, “but I’m not going to pretend I don’t get Botox.” That attitude helped her deal with one friend who, she says, rolled her eyes at Hughes’s enhancements. “She alluded to the self-indulgence of [it] and mocked the “cat people” who overdo plastic surgery.” Hughes was unfazed. “Own it. You’ve only got one life,” she says, noting that her judgmental friend recently returned from the dermatologist with a $100 bottle of eyelash lengthener. “So we know who won that battle.”

I eventually took my cue from my hairdresser who’d inspired me to get lash extensions by looking so fabulous with her own. “Yeah, they’re fake,” I would say when I noticed someone looking intently at my eyes. It felt liberating to come clean.

Not long ago, however, I bumped into a woman I hadn’t seen in a few years. She also had lash extensions and a whole lot of other work about which I couldn’t honestly offer a compliment. I opted for small talk about our kids and mutual friends.

Good call, says Smith. It used to be that “not saying something was a major statement. Today, no comment doesn’t have the same sting.” What’s more, “most of us are not very convincing liars.”

When we witness someone who’s had bad or too much work, says Diller, “we’re witnessing someone who’s been pulled into the current. They’re trying to hold on to something they can’t. Your heart breaks…” She recommends we “look past those changes,” offering up that it’s “so great to see you.”

Moelleken agrees. “Badly done plastic surgery is a deformity,” he says. “Treat it the same way you would a deformity. It’s not polite to call attention to it.”

It’s a sentiment that sums up how we should respond to any cosmetic enhancement, says Smith. Whether or not people want to talk about what they’ve done is up to them. If it is brought up, “tread lightly,” she says. “I believe in honesty but I don’t believe in hurtfulness.

Image: Getty