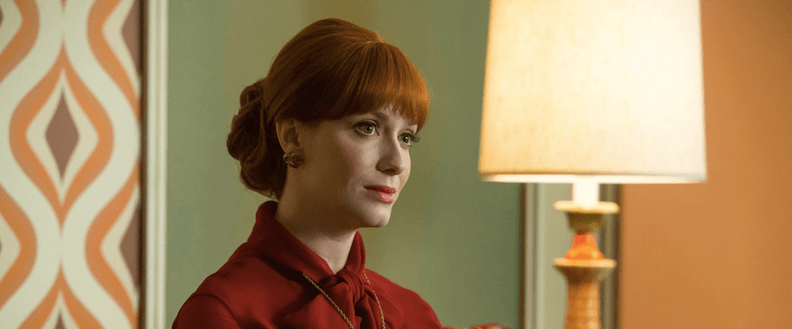

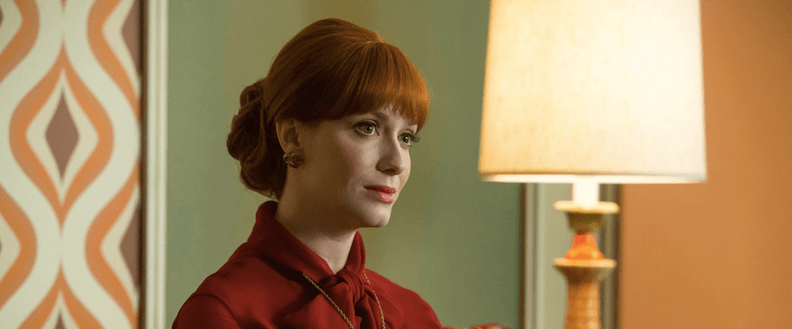

AMC

Joan and Ken Are a Perfect Study of “Mad Men’s” Sexism

They’ve devoted their lives to Sterling Cooper, but another merger results in their humiliation. Both can afford to leave. But only one of them has a place to go.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

As we head into the second episode of Mad Men’s final six, I wanted to take one last look at Sunday’s episode, where Ted literally brings Don a binder full of women. If anyone doubted the show’s ongoing commitment to portraying sexism in the workplace, that ought to take care of it.

And Joan, once again, is at the forefront. In the first season, Roger gave Joan a bird in a gilded cage, an unsubtle symbol of how he thought of her. As the series draws to a close, Joan has an executive office and a life-changing pile of cash in her bank account, but she’s as trapped as ever.

It’s natural to compare Joan with Peggy—and they do so with each other, in the elevator scene in which they take out their frustrations on each other after enduring a nauseating display of misogyny from their male colleagues. But let’s look at another parallel that no one, including the characters themselves, seems to have noticed: Joan and Ken Cosgrove. Both Joan and Ken have had their bodies used as playthings by clients. Joan prostituted herself to land the Jaguar account (and her partnership); Ken was shot in the face by hard-partying Chevy executives. All their colleagues know. Their very bodies serve as constant reminders of their sacrifices.

Why don’t either of them ever acknowledge it? Why don’t they see each other as natural allies?

Ken and Joan both chafe against gender norms. Ken has no interest in examining his privilege—he accepts the existence of homosexuals and the Irish but would prefer not to work with them—but little interest in playing the alpha-male game, either. He wants a work-life balance and time with his family. He values his fiction writing and the bond it creates with his bookish wife. As a man, Ken doesn’t put his professional credibility at risk by talking about his son in the workplace. Joan doesn’t have that luxury—but let’s face it, she doesn’t seem to want it, either. Has Joan ever seemed more gloriously, triumphantly herself than in her Topaz strategy scene with Don, stealing his cigarettes and commiserating with him over the cluelessness of others? Profit-minded, workaholic Joan is, frankly, a far better fit for macho business culture than the nature-loving, tap-dancing Ken.

The executives of McCann Erikson, the firm that bought Sterling Cooper at the end of first half of season seven, force Roger to fire Ken and humiliate Joan and Peggy during a business meeting. In the aftermath, Ken and Joan both have it pointed out to that they have enough money to leave Sterling Cooper—and any necessity of paid employment—behind for good. (Yet another ironic gender-bend: Joan’s original life plan was to marry someone who could support her in luxury for the rest of her life. Ken actually did.) So why don’t they leave?

For much the same reason they don’t recognize each other as allies: Pride. A desire to protect the ego at all costs, to prove that what we endured was worth it. Identification with the aggressor. These are universal human tendencies that, paradoxically, prevent us in the moment from seeing what we have in common. Tendencies that narrow our vision until we can only see who is above us and who is below, and cannot see the legions standing next to us.

WASP Ken humiliates Irish Ferguson McCann who humiliates sexy Joan who humiliates plain Peggy who humiliates her veal-eating date who breaks the cycle of abuse and gives her a whopping ego boost so she turns on her hilariously inept Peggy Olson equivalent of charm and gives him her cannelloni (it’s complicated).

Ken, shot in the face by a client, joins an actual weapons manufacturer on the client side. By the end of the episode he is almost literally holding the hydrogen bomb over the heads of Roger and Pete. Joan is more constrained in her ability to lash out. Shamed, she shames Peggy in an elevator scene meant to tie back to season four’s “The Summer Man.” In that episode, Peggy fires one of her underlings for drawing obscene cartoons of Joan, only to be attacked by Joan for her overt feminism. In “Severance,” Peggy is the one with the more pragmatic, accommodationist view: “Would you have rather had a friendly ‘no’?” she points out—but Joan attacks her anyway. Like most real people, the Mad Men characters are motivated more by instinct than by consistent ideology. (The real mystery is why Peggy even gets into elevators with Joan anymore.)

Ken and Joan, both wounded, lash out. But Ken has more options than Joan and always will. The horrifying bodily sacrifice he made to keep a client didn’t come with a side of shame. Her prostitution will haunt and discredit her entire professional future. Ken’s injury, by contrast, would make him look even more compelling and intriguing on a book jacket, as Pete helpfully points out.

“Well aren’t you lucky, to have decisions,” Peggy spat at Ted in season 6. The same theme carries through this year. Over and over again, “Mad Men” shows us, the end result of sexism is that men have more freedom to navigate the world, more ports in which to land. As I’ve written before, Joan is trapped at Sterling Cooper. She has financial security, but no freedom.

Contrast that with Ken. Going to Dow isn’t the road-less-taken that he claimed to dream of—but as Don’s waitress-prostitute pointed out, we often lie to ourselves about our dreams. It’s possible that deep down Ken wants fiction writing to be his mistress, not his wife, professionally speaking. But even if the Dow move betrayed his deepest desires, it doesn’t foreclose any options for him. He can quit them tomorrow, if he wants, and go write that novel. Ken may not be comfortable leaving the world of office politics behind, but isn’t he lucky to have decisions? Joan, by contrast, has nowhere else to go.

Joan is left with the incandescent rage to “burn this place down.” But Ken’s the one who’s got the napalm.

Robin Abrahams writes the Miss Conduct advice column in the Boston Globe. Follow her at robinabrahams.com or on Twitter @robinabrahams.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.