It may be romantic to tie outsize creativity to mental illness and mythologize the suicides of artists like Kurt Cobain and Robin Williams. But is it causing more harm than we realize?

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

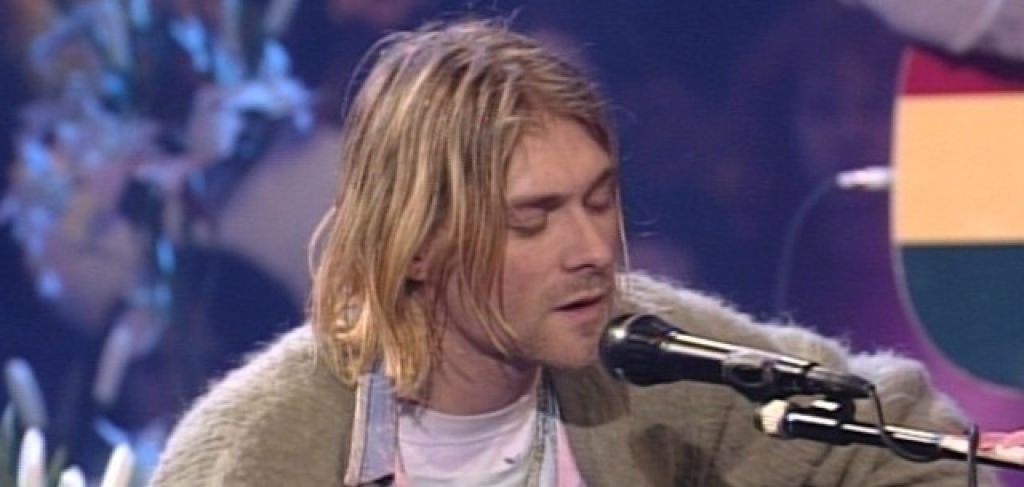

I can’t believe it’s been more than 20 years since the suicide of Kurt Cobain, the charismatic front man of Nirvana. Images of his 27-year-old face—those piercing blue eyes, his stringy blond chin-length hair, framing the sharp contours of his unshaven face—seem ubiquitous right now, because this month marks yet another anniversary of his death, and with it comes a documentary, Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck, opening on Friday (and airing on HBO on May 4), and innumerable features in both print and online magazines everywhere (not least of which, the cover story in the April 23 issue of Rolling Stone), all of which are making me feel wistful and heartbroken all over again. Because all of it is catapulting me back to one magical November night during my senior year in high school, when my girlfriends and I risked serious punishment by staying out well past curfew to see Nirvana on their “In Utero” tour.

It was well worth it: We had the rare opportunity to see them in a small venue, the Armory in Philadelphia, and be among 3,000 members of our “slacker” generation. It would be the last time we’d see them. Because a few short months later, Cobain would be gone.

Like so many others, I was shocked when I heard about his suicide—I was listening to the radio when the news broke regular programming. Not only because of the news itself, but because he wasn’t much older than me, and his death felt all too real and uncomfortably accessible. I had just seen him, up close. He’d been singing to me, my friends, and a few-thousand other kids of our generation, not that long ago—and now he was … dead? I was 17 at the time, trying to wrap my mind around it. Kurt Cobain was the first famous person to whom I related who had done something so tragic. He had committed suicide.

My friends and I struggled to make sense of this unthinkable act. If Kurt Cobain could end it all, when he had a wife and new baby, when he seemed to have, what appeared to us like the perfect life, we needed to figure out the logic of his violent act.

And we came up with one: We had decided that it was his genius that killed him. That being brilliant and talented was too much to bear.

Now you can debate whether Cobain was a genius, but there is little doubt that he changed the entire landscape of popular music in the early 1990s. As Sarah Larson wrote in The New Yorker, “My generation talks about hearing Nevermind for the first time, and seeing ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ on MTV, the way our parents talk about seeing the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show.”

There was something romantic to our young, naïve minds about the idea of a tormented, suicidal genius: it’s tragic; it’s even beautiful. Our belief in death-by-genius allowed my friends and I say good-bye to our hero with respect.

The problem is that the suicidal genius, the tormented artist—and all such similar stereotypes—they are a sleight-of-hand, a sideshow, and not respectful of the dead, or the living, at all.

Every time a famous actor, writer, or other artist commits suicide, arguments come pouring in about the supposed connections between creativity, genius, and the tormented artist. The suicide of Robin Williams last year once again brought these supposed connections to the fore.

But how does the stereotype of the “mad genius” affect actual people living with psychiatric disabilities?

Psychiatrist Nancy Andreasen, who claims “dual identities as a scientist and a literary scholar,” is one of three leading scientists interested in drawing connections between mental illness and creative genius (along with Arnold Ludwig and Kay Redfield Jamison). Just last summer, Andreasen reported on her ongoing work searching for the “Secrets of the Creative Brain.” In her feature, which was published in The Atlantic, she wrote about how she analyzed cutting-edge MRI scans of creative people’s brains, looking for, as she puts it, “a little genie that doesn’t exist inside other people’s heads.”

Some scientists—but few journalists—speak against this “mad genius” research, despite a lack of strong scientific evidence to support what is essentially a Romantic stereotype. And that’s big-R “Romantic.” For example, as evidence of creative genius, Andreasen recounts an old tale wherein Samuel Taylor Coleridge composed his epic poem Kubla Khan “while in an opiate-induced, dreamlike state, and began writing it down when he awoke.” But, alas, he “lost most of it when he got interrupted and called away on an errand.” Errands, it seems, are not romantic.

Andreasen’s work gets a lot of airplay because we as a society are fascinated by the notion of the mad genius. But this fascination has negative consequences for people with psychiatric disabilities. The issue here is whether the mad genius stereotype—the stereotype that psychiatric disability and creativity are somehow linked—gets in the way of saving people’s lives or making their lives more livable.

And there is real evidence that it does.

The mad genius stereotype limits how people with psychiatric disabilities are allowed to exist in the world. As psychologist Judith Schlesinger notes, focusing on the mad genius treats people with “exceptional gifts” as psychologically abnormal. If you are a genius with a mental illness, then you are at risk of being pathologized by doctors eager to scan your brain looking for “little genies.”

If you have a psychiatric disability and you are not a creative genius, then all you have left is a broken brain.

Either way, research and clinical experience shows that the mad genius stereotype affects how people with disabilities seek and receive treatment, whether we work in creative fields or not.

For example, the mad genius stereotype hurts because it creates yet another stereotype that people with psychiatric disabilities have to fight against—and we have enough of those. We already have to deal with various kinds of stigma—the stigma of irrationality, for example, and the stigma of dangerousness. Because of stigma, those of us with invisible disabilities often opt to pass as non-disabled to avoid being mistreated by neurotypical (i.e., non-disabled) colleagues, friends, and family.

The mad-genius stereotype creates even more stigma.

Here’s an example. Say you work in a field that prizes calmness, rationality, reason, and predictability—qualities that are opposite of those possessed by the stereotypical mad genius. Say you are a lawyer, even a genius lawyer—a law professor. You would likely be terrified that anyone might find out about your mental illness, like law professor Lisa T. McElroy used to be before she decided to break the silence of her mental illness in Slate.

Why wouldn’t you be afraid? After all, people believe that mad geniuses are mercurial and unpredictable. They put their heads in ovens (like Sylvia Plath), walk into rivers (like Virginia Woolf), and cut off their ears (like Vincent van Gogh).

If your legal employer were to discover your psychiatric disability and believe the stereotype of the mad genius, your employer might believe that you were unfit for your job. You are a mad genius, and therefore not lawyerly; you are not calm, rational, reasonable, or predictable. (Never mind that recent studies show that law students and lawyers have some of the highest rates of mental illness of any population in the United States—approaching 40 percent.)

The mad genius stereotype attacks from two angles: No creative person can live up to the immense psycho-biographies attributed to Sylvia Plath or David Foster Wallace. And no law professor can provide enough reassurance to her dean, when her dean is afraid that she will deliver her lectures in opiate-induced dream-like states.

But the mad genius stereotype affects more than just the way that neurotypical people view people with psychiatric disabilities. It affects how people with psychiatric disabilities view ourselves and the decisions we make about our treatment.

For example, as a way of battling self-stigma, people with psychiatric disabilities sometimes deliberately request certain diagnoses from their doctors—in particular, bipolar disorder. Patients associate this diagnosis with, among other positive attributes, being creative. Indeed, psychiatric researchers Diana Chan and Lester Sireling observed that “self-diagnosis of bipolar disorder” reflects the patient’s “aspirations for higher social status, as illustrated by the implicit association of bipolar disorder with celebrity status and creativity.” In short, patients want to be bipolar because news coverage of the mad genius stereotype depicts bipolar disorder as cool.

Dr. Kenan Penaskovic, Medical Director and Associate Clerkship Director of the Department of Psychiatric at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, has found in his practice that “some patients gravitate toward illnesses that may be perceived as more socially acceptable or that carry better prognoses.” Bipolar disorder is certainly one of those “better” illnesses. Schizophrenia and borderline personality disorder are examples of illnesses that patients gravitate away from, he notes. Patients with schizophrenia and borderline “may strongly prefer to be classified as bipolar” both because bipolar disorder has “a better prognosis” and because it is “more socially acceptable” than either schizophrenia or borderline personality disorder.

But why is bipolar disorder becoming more socially acceptable? Dr. Penaskovic recognizes that it is “in part due to celebrities.” And although he is glad that the stigma against bipolar disorder seems to be lessening, he notes that “it is important to remember that most individuals with bipolar disorder are not extraordinarily creative.” Rather, they “more commonly suffer from devastating depression and debilitating manic episodes.”

The fact that bipolar disorder tends to be a disease with terrible symptoms has not stopped the rise in its diagnosis. Dr. Penaskovic pointed out that the editors of the DSM-5, the latest edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders put out by the American Psychiatric Association (released in 2013), “recognized bipolar was being more commonly—and potentially overly—diagnosed,” and the editors have altered the diagnostic criteria to account for this rise in diagnoses.

In addition to causing “diagnosis shopping,” the mad-genius stereotype also affects how patients respond to their doctors. Researchers find that patients are citing creativity as a reason for refusing to take their medications or ceasing all treatment for their psychiatric disabilities. Doctors report that their patients believe—often without evidence—that their treatments will cause them to lose their creative genius. There is ample scientific evidence, however, that their treatments will prevent psychosis, depression, and death, without affecting creative output at all.

Much has been written in the popular press on both sides of this treatment/creativity debate. Gila Lyons asked rhetorically (in The Millions), “What if the touch of the madness had been medicated out of van Gogh, Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Faulkner, Sexton, Plath, and [David Foster] Wallace?” in her essay debating whether she herself should take psychiatric medication. Her words imply belief in the mad genius stereotype, which holds that, first, creativity is necessarily tied to madness, and, second, that creativity is a thing that can be “medicated out” of a person.

In direct response to Lyons’s piece, Tasha Golden wrote (in the Ploughshares blog) that “the fear of control feeds the myth that creativity is some kind of Mysterious, Mad Magic. It’s not.” She points out that an over-reliance on “Magical-Muse thinking” actually disempowers creative workers. She suggests setting aside belief in such thinking to “empower ourselves and each other to make more and better work. And to be healthy while we’re at it.”

Lyons’s and Golden’s words reveal in a public fashion the struggle that many patients have faced privately. Because of the mad genius stereotype, patients in creative fields (and even those who aren’t) make treatment decisions that they believe will make them more creative. These decisions often come at the detriment of their health, as Nancy Andreasen herself has observed. In particular, for patients with bipolar disorder, Andreasen has noted, “Some feel that the high energy levels and euphoria associated with manic or hypomanic states enhance creativity”—and her patients are afraid to lose that perceived enhanced creativity.

In response to this belief, and perpetuated by the mad-genius stereotype, patients often choose to forego psychiatric treatment, whether medication or therapy. But, as Andreasen’s and others’ research has shown, scaling back medication is usually the wrong course of treatment, even for creative people with bipolar disorder. Andreasen advocates instead for a normal course of treatment for bipolar patients, observing “it is likely that reducing severe manic episodes may actually enhance creativity in many individuals.”

Tasha Golden wrote, in her own polemic against the mad-genius stereotype, “I’ve written far more post-depression than I ever did before.” Indeed, as Kay Redfield Jamison observed in a report on her mad-genius research for Scientific American, “No one is creative when severely depressed, psychotic or dead.”