You aren't slapping "sense" into your kids: Brain scans reveal the devastating, enduring effect corporal punishment has on young adults.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

“Whore.”

“High-end coon.”

“Racist!”

“Liberal.”

“You need a spanking.”

“You’re a moron who purchased her Ph.D. from Walmart.”

These are just a few of the comments that followed my recent piece about why Baltimore mother Toya Graham was not a hero for beating her 16-year-old son Michael Singleton upside the head. My inbox and Twitter feed blew up with nasty comments from Black and White people who crowned her “Mother of the Year” for trying to “knock some sense into her son’s head” during a Baltimore riot last month. It is ironic that people who see hitting as the best parenting strategy to produce well-behaved children have a moral compass that is clearly broken and unable to have a conversation without using language that would make Archie Bunker blush.

Rather than logically arguing why they disagreed, I was cursed out and dismissed as stupid. A Black megachurch pastor said that my mama, who is deceased, needed to whoop me. A Black Christian news site criticized me for not giving my “good adoptive mother” credit for the beatings that scarred my face and sent me into foster care.

In addition to citing the usual Old Testament scriptures to promote hitting kids and calling physical discipline an act of “love,” others deviated from the ad hominem playbook to make their points with anecdotes:

“I was spanked and I turned out fine.”

“There’s a thin line between spanking and abuse.”

“That wasn’t a beating that Toya Graham gave her son. She didn’t hurt him.”

Many said they’re not on drugs, in jail, or prematurely dead because they were whooped as kids.

These recycled and parroted comments reflect the power of personal bias and our society’s continued aversion to science. While frustrating, forgive them for they cannot control what they say. Given the scientific research about how being spanked impacts the developing brain, one has to wonder: Is there a correlation between the justifications, defensive reactions, anger, name calling, lack of impulse control, hostility, incivility, and the inability or unwillingness to have healthy exchanges over this issue, and the structural damages that spanking has on a child’s developing brain? We’ve all heard the cultural mythology surrounding how corporal punishment primes people to become better adults, but what does the science say?

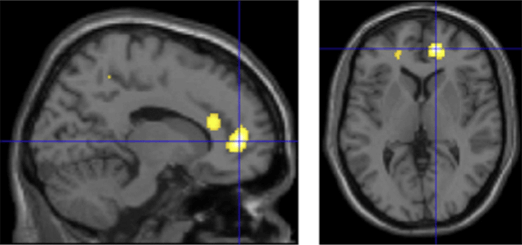

Rather than relying on America’s stand-by source for all knowledge—Google—I sought an expert in the field: Dr. Martin Teicher, a neuroscientist at McLean Hospital and Harvard Medical School who has over 30 years research on child maltreatment that shows the consequences of corporal punishment on brain scans. [See brain scans below]

Dr. Teicher has studied the impact of maltreatment—sexual and verbal abuse, witnessing domestic violence, and corporal punishment—on the development of a child’s brain. During his residency training in psychiatry, he observed in brain scans of a few patients suffering from borderline personality disorder, suicide attempts, and symptoms suggesting of temporal lobe epilepsy. Many of these patients have noticeable shrinkage of the hippocampus—that part of the brain used to form memories, organize and store information and is responsible for emotional management, logic and reasoning skills, self control, and communication. He noted that all of these patients had one thing in common—severe childhood maltreatment.

For the last decade, Dr. Teicher and his team at Harvard Medical School scanned the brains of hundreds of subjects who experienced regular corporal punishment, those who were severely abused, and those that had no exposure to corporal punishment.

In 2008, he and his team completed a five-year neuroimaging study of the impact of corporal punishment on the brain. He scanned the brains of 46 mainly middle-class, well-educated subjects, half who had been corporally punished and half who had not. “All the subjects that we looked at were hit at least once a month, through several years of childhood,” he said.

The consequences are not abstract or only visible on the brain scan. His work and that of other researchers shows that spanking is associated with aggression, delinquency, low IQ, mental-health problems, and drug and alcohol abuse. A recent study from The Journal of Adolescent Health found that almost 50 percent of youth 16 to 18 years had a traumatic brain injury prior to their incarceration.

Many people say there’s a thin line between spanking and abuse. Crossing that line is often defined by the visible injuries: The sight of a bruised child, broken bones or blood streaming from a child’s body, and charred skin is where we draw the line. If medical intervention or Child Protective Services is needed, it fits the definition of abuse. While none of the participants in Dr. Teicher’s study fit this category, their brains still told a story of trauma and injury that will last a lifetime.

Gray matter volume in portions of the prefrontal cortex was reduced by 19 percent in the maltreated youths compared with those who were not hit. MRI scans distinguish gray matter, which consist of the nerve cell bodies and connections, and white matter, which constitute the fiber tracts interconnecting gray matter regions of the brain.

“The prefrontal cortex is the last maturing part of the brain and it is associated with impulse control, executive function, the ability to make right decisions, judgment, learning, being productive in life, being able to correct and modify behavior, being able to infer what others are thinking and feeling. This is what we rely on for higher cognitive function. Harsh corporal punishment appears to compromises this,” he said.

The brain scans of corporally punished young adults showed nearly 20 percent reduction in the volume of gray matter in certain areas of the prefrontal cortex of their brains, compared with those who were not hit. Gray matter is associated with intelligence and intellect, Dr. Teicher said, and harm to that region is linked to depression, addiction and other mental health disorders.

Dr. Teicher’s research reveals that stress hormones associated with child maltreatment can damage the hippocampus, which may in turn affect the ability to cope with stress later in life. These children are at risk for mental illness, but because of the way trauma affects the stress system, they are also more vulnerable to developing chronic diseases like diabetes, high blood pressure, heart attack, and stroke. No wonder America is last in many categories of health and wellness throughout the industrialized world. Access to health care is one issue; a culture that imagines abuse as love and good parenting is another cause.

Corporal punishment is also linked to increased risk for depression and substance abuse, Dr. Teicher said. “Physical maltreatment is a causal factor in drug addiction. A potential impairment in the parts of the brain that receive the neurotransmitter dopamine puts a person at risk for addiction.”

Exposure to corporal punishment or high levels of parental verbal abuse, or witnessing domestic or sexual abuse affects the sensory system and determines how individuals will respond emotionally or remember the trauma. “When you’re exposed to something very stressful, seeing or hearing something horrible—a parent cursing at you, calling you stupid, or getting hit really hard—your sensory system gets modified,” Dr. Teicher said.

He was shocked when he discovered that 60 percent of the subjects in his study admitted that corporal punishment was the best thing that happened to them. Not surprisingly, they said would do the same thing to their children. This was likely a consequence of only including subjects who received corporal punishment for discipline and whose parents were in emotional control at the time.

“Individuals who have witnessed domestic violence or experienced verbal abuse didn’t talk about it fondly. But even though being hit is, on a neurobiological level equally traumatic, they reframed and rationalized it in a positive way,” Dr. Teicher said. “They saw corporal punishment as an effective form of discipline. Their parents were trying to help them become a better person. They say, ‘It made me who I am and it is something I want to repeat with my kids.’”

The defense of corporal punishment, the dismissal of the science, and the vigor and violence evidenced in their argumentation is not surprising. People defend what happened to them “because if I say it was a bad thing that hurt me, set me back and challenges me as an adult, that will truly be upsetting and will cause me to reframe how I view my parents, my childhood, my religion. It will call into question a number of things I don’t want to question,” says Dr. Teicher. “But the science tells us that corporal punishment is a failed experiment for producing a beneficial protective effect against antisocial behaviors or incarceration.”

The next empirical phase of his research will be to compare the brain scans of people who received traditional corporal punishment and those who were severely abused. His hypothesis is that there’ll likely be little or no significant differences in the consequences.

Dr. Teicher’s research challenges the popular mythology that corporal punishment turns naughty kids into productive adults, that it makes for a healthier society.

If you are a person that continues to believe that spanking is a good thing, you didn’t turn out fine. Perhaps it is a sign that your brain has been so altered that you turned out to be someone who thinks it is okay to assault children.

BRAIN SCAN 1: This scan shows a statistical analysis of the prefrontal cortex region of the brain where there was a significant reduction of gray matter density in young adults age 18 to 25 with histories of harsh corporal punishment as compared to those with no history of being hit. These subjects had no history of head trauma, substance abuse, fetal drug exposure, exposure to physical, sexual, or emotional abuse that might have influenced brain development. This is a region of the brain involved in regulating emotion, aggression, attention, and cognition.

BRAIN SCAN 2: This scan shows a statistical analysis of areas of the brain where there is reduced brain activity in young adults with histories of harsh corporal punishment. Highlighting regions of the brain with less activity in young adults with history of harsh corporal punishment.

NOTE: The American Academy of Pediatrics has defined corporal punishment as the striking of a child with an open hand on the buttocks or extremities with the intention of modifying behavior without causing physical injury, as an acceptable but less effective strategy than time-out or the removal of privileges for reducing undesirable behavior. However, striking a child with an object, such as a paddle, strap or brush, for the same purpose in considered by the AAP to be an excessive, inappropriate and unacceptable means of discipline. That said, Dr. Teicher and his team define “harsh corporal punishment” as the chronic, relatively frequent use of physical punishment—like what Toya Graham did to her son—but did not result in physical injury.