The writer's Rush Limbaugh-loving dad made her promise never to become a "feminazi." Even as he raised her to be smart, outspoken, independent—and to feel entitled to equal rights.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

On family road trips—in between listening to a soundtrack that would include Fleetwood Mac, Jerry Jeff Walker, the Moody Blues, and the Beatles on the car stereo—my mom would read to my dad. Or I would. Or one of my sisters. Sometimes it was from unread copies of The El Paso Times that had been collecting dust in our living room. Or from a book one of us was reading for school. Sometimes it was select passages from The Book of Virtues, William J. Bennett’s anthology aimed at teaching children to develop character. Every once in a while, if the most recent copy was still unread, it was Rush Limbaugh’s eponymous print newsletter, “The Limbaugh Letter.”

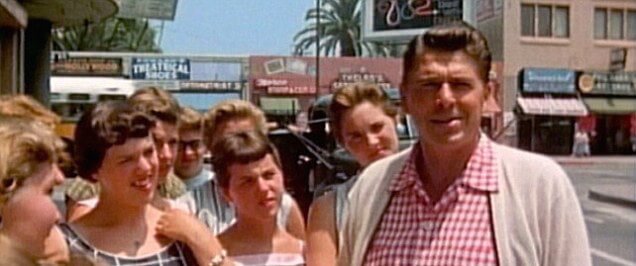

Twenty-five years earlier, Jimi Hendrix and Joan Baez and Bob Dylan had guided my father to dissent; as a hippie he once got into a fistfight with his own father over the length of his hair. But my father was born again, politically, during the Reagan administration. Years after the Gipper left the White House, Dad was still a dissenter, but now one to the right of the political divide. His construction business was thriving, and Clinton-era tax reforms were seen as a threat to our family’s finances. Limbaugh’s writings and radio presence showed my father that he was not alone in his ire toward the administration, and provided him the vocabulary of the opposition.

It was during these first few years of the Clinton administration when Rush Limbaugh first popularized, and I first heard, the term “feminazi.” Still too young to have a full grasp of what feminism was, but old enough to have learned about the atrocities of the Holocaust in my Jewish Sunday School classes, I came to believe that the women Dad and Limbaugh railed against, chief among them the new First Lady, were the worst of the worst: pantsuit-wearing man-eaters who were determined to kill babies and emasculate men. Dad made it clear that no daughter of his—and there were three of us—should ever identify as a feminist.

And yet …

Maybe because my father never had a son, or maybe because he had three sisters, or maybe—just maybe—equality and fairness mattered more to him than gender roles, my father brought us up in a way that pointed me, quite organically, down a feminist path.

“Boy toys” and “girl toys” didn’t matter. I had Barbies and Hot Wheels. I held my Cabbage Patch doll in my lap as I sat in Dad’s, watching Grand Prix racing and every so often sneaking a sip of his beer. Dad encouraged us to be athletic, sometimes to my chagrin, organizing family rollerblading outings when I would have much rather been curled up with a book. Over weekends and holidays, he would bring us to his job sites and have us sweep sawdust and help him with punch lists, holding a level or the end of a tape measure and yelling our findings to him. We would help him wash and service the vintage Jeep that sat in our driveway for years. Though a Barbie released when I was a child proclaimed “Math is tough!”, he never tolerated poor performance in math or science classes, because, to him, those were important lifelong skills.

My outspokenness was encouraged, my independence cultivated. I was precocious, inquisitive, and furiously smart. If anyone told me I couldn’t do something, my dad would say I could. If anyone told me I couldn’t do something because I was a girl, or if, God forbid, I said that myself, my dad would call it a lie. I wanted to be the first woman president, so Dad had helped me calculate that I would be eligible for the 2020 election. He even would say I didn’t need to focus on the “woman” part when people asked what I wanted to be when I grew up, because emphasizing gender made it sound like a handicap. I wanted to be president. Simple as that. And I could be, too.

Then I got older. Old enough to vote. Our political ideologies began to diverge. I realized that voting like my father meant voting against the best interests of people I loved. I remained a registered Republican. I continued to deplore the idea of feminism, as I’d come to understand it, but I also became increasingly aware of the realities of being a woman in a man’s world. I began to embrace the ideals of feminism without even realizing it. I finally “came out” to myself as a feminist halfway through college. I registered as a Democrat.

About every man I dated in college, a question from my father: Was I being treated well? He wasn’t asking because he wanted me to be taken care of, but because he wanted me to be respected. As I sobbed into the phone with the news that my long-term boyfriend and I had parted before senior year, Dad reminded me that I should never rely on a man so wholly that I lose the wherewithal to rely on myself.

From my first “grown-up job” on, Dad would ask about my salary. He didn’t care about the number, but the parity. Was I making as much as my peers? My male peers? Was I getting the same benefits and the same time off? Did I try to negotiate for more? And his questions went beyond salary: Was I being respected at work? Were my opinions being valued? Was I appreciated? If the answer to any of those questions was “no,” and the situation did not seem like it would improve, my father made it clear that I could, and should, find a better position elsewhere. Stasis was not an option if it meant continuing to flounder.

But if asked about the existence of a glass ceiling for women, or if an Equal Pay Amendment were necessary, my father would most definitely say “no.” In his mind, my successes are attributable more to my personal intelligence than to his insistence or mine to buck the status quo And the challenges I’ve faced, of course, are never simply because I’m a woman, but because of personal failure. What I identify as feminism, my father would identify as rugged individualism.

Growing up across the border from Juarez, Mexico, my father taught me how to negotiate—in English and Spanish—on frequent trips to the Mercado. The stall vendors were frequently bemused to find themselves haggling with the confident, underage gringa. Dad taught me to never trust a man who softened his handshake because a woman was on the other end of it, and the value of steady eye contact with any person who was trying to make you feel like less than you are.

This all came in handy when, earlier this year, I found myself in need of a new car. After the manager at a local dealership tried to size me up and greet me with a weak handshake and a hard sale, I decided that no matter how much I liked the car I drove there (and I did like it), I was not kind of woman who would fall for a weak attempt at a hard sell, nor did my father raise me as such. I left the lot and went straight to one we’d visited earlier, where I was able to negotiate great terms on the car that I wanted, not the car that a man told me I should be driving. (That this salesperson was a woman was a bonus.) It was one of the most tangibly feminist things I’d ever done—something I did rather than something I debated. As I drove off the car lot after a strong congratulatory handshake, I said a silent “thank you” to my father for giving me the tools to be the woman I am today, and smiled with the knowledge that he’d be proud of me—even if that woman is now one more likely to read Roxane Gay than Rush Limbaugh, or The Feminine Mystique than The Book of Virtues.

Even if that woman is a feminazi.