Black America, unlike White America, needs to televise the funerals of our tragic victims to elicit sympathy and to compel outrage and action from the rest of the nation.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

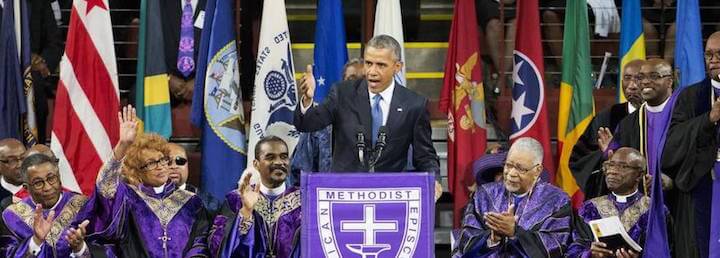

Um, so, I want to talk about the swoons and raves over the 37-minute performance that President Obama, a.k.a. “Reverend President” and “Eulogizer-in-Chief,” gave last Friday at Reverend Clementa Pinckney’s funeral service, with many people saying that his blackness was on fuller display than it has been throughout his time in office.

Unless you’ve been under a rock or in a coma, Pinckney, who was also a state senator, was killed with eight others during a prayer meeting at the Emanuel AME Church, on June 17. Their killer, a young White racist terrorist now in police custody, sat in the sanctuary with his victims for an hour before shooting them. (After the cops caught that degenerate-looking, throwback, peckerwood bastard and treated him like a king deserving of a burger and a red carpet, he had the audacity to say, “I almost didn’t go through with it.” Oh how I would love to get some straight medieval justice on his ass: bury him to his neck in the dark brown South Carolina dirt, in the hot fucking sun, with no water. Then let Django whip him into oblivion with a wet Confederate flag while the Harlem Boys Choir sings Negro spirituals.) Let CNN air that instead of the daily processionals of dead Black bodies flanked by destroyed Black families and communities.

I watched the president deliver his eulogy through a live stream. As he stood behind the pulpit, flanked by AME ministers, he appeared like a preacher, playing off the energetic, mostly Black audience with the organ backing up his words. Near the end of his eulogy, he looked down at the podium and took a long pause. And then suddenly, he broke out into a rendition of “Amazing Grace” in a baritone that was, as one of my friends put it, not nearly as soulful as his falsetto rendering of Al Green’s “Let’s Stay Together.”

The crowd loved it. They stood to their feet, clapped, cheered, and recorded the moment with their cell phones. The interwebs loved it. #AmazingGrace surely trended on Twitter. And the media ate it up.

Writing for The Atlantic, James Fallow said: “I think Barack Obama’s eulogy yesterday at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston was his most fully successful performance as an orator.” Fallows also said, “His singing was the aspect of the speech that will be easiest to remember. That is in part because it was so unusual and in part because it was so brave: Obama sang well, but not perfectly.”

Yes, the first Black president can sing and dance. Yet, the disturbances run deep during these spectacles.

Obama’s performance, and the televising of another Black funeral, is yet another reminder that White America loves Black suffering. And, all too often, televised Black funerals offer ministers and political figures media exposure and a chance to score political points. They provide traumatized Black communities a stage to perform respectability for White America. And televised Black funerals also give White America the desired pleasure and catharsis necessary for the preservation of a racist status quo. Over and over again, Black funerals have been co-opted and disseminated as a way to affirm White America.

“It created the illusion, for that one moment, that we were finally coming together as a nation to heal our racial wounds when we are avoiding all the hard choices that need to be made to actually do that,” said Mark Naison, a professor of African-American studies and history at Fordham University.

On a Facebook status update, Khadijah Costley White, an assistant journalism professor at Rutgers University wrote: “Black president raised by White folks sings a song written by a slave trader in a Black church with an organ playing in the background while eulogizing Black folks killed by a White supremacist on the same day same-sex marriage becomes the law of the land. I’m so confused.”

Gazi Kodzo, an activist with nearly 80,000 followers on social media told me in a chat conversation that Obama is “playing African people just like White people play us. It’s extremely insulting. Even worse than the time Bill Clinton horribly played the saxophone on Arsenio Hall. Obama did that preacher performance to create a narrative to African people: ‘The president is on your side so calm down that Black rage.’”

Kodzo added, “I suggest Barack Obama select less problematic songs when trying to sedate Black rage. ‘Amazing Grace’ was written by a White slave-ship owner. Next time pick from the many Negro spirituals that were written and composed by Black slaves, or maybe that’s too Black for him. Black people need an answer from the most powerful Black person in the world. Not a sermon from a tone-deaf preacher. We have enough of those, thank you.”

The televised funeral does offer Black people and those who are emotionally impacted by the tragedies a sense of community. These moments allow for us to collectively grieve these victims, many whose names were not known publicly until their horrific deaths.

When racial killings happen, the Black funeral provides a space and time for the grief and loss of the living—the family and the community—to be soothed as the living say good-bye to the deceased. As scholars of Black funeral tradition have noted, these services are about ritualistically expediting the journey of the dead to the next world and restoring the social and emotional equilibrium of the family, friends, and community. It’s about context, closure, and providing a collective catharsis.

The Black church has long been a site of redress and reconciliation. After living lives ravaged by prejudice and discrimination, funerals are a posthumous attempt to praise the deceased for “fighting the good fight.” The music, eulogy, the open casket, and the practice of uninhibited emotion—crying, shouting—help to generate a positive sense of self-identity for the deceased and the mourners alike in a nation where Black lives don’t matter.

Historically, the visibility of Black funerals highlights Black respectability and über-Christian ethic to prove Black Americans’ worthiness to be accepted into the national fabric. Televised Black funerals are also a means of “shaming” America. The message is, “If only, White racists had a conscious, had the ability to see our humanity, and to feel our pain.”

African Americans have used funerals, from Emmett Till to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.; from Trayvon Martin to Senator Clementa Pinckney to compel action. The sight of Black death has been elevated in hopes of forcing White America to stand at the crossroads of moral outrage and their acceptance of racial degradation and violence. The hope has always been that when confronted with the death and consequences of anti-Black racism, when brought face-to-face with the suffering, pain, and humanity of Black America, White America would choose the path toward justice. We know all too well this has not happened. White supremacy denies Black humanity in life and death.

But there has also been historical ambivalence in Black communities about the deliberate use of funerals as activist theater. During the Civil Rights Movement, some faith leaders fought against media intrusion into the sacred space of their church congregations. One of the families of one of the four girls who died in the 16th Street Baptist church bombing in 1963 refused Dr. King’s efforts to make her funeral into a spectacle.

And of course there was Mamie Till’s decision to allow JET Magazine to publish that graphic photo of her son’s swollen, mutilated face. But let us remember the Black press published that image; its impact would be seen with northern Blacks and with leverage it provided Black civil-rights organizations the ability to bring global attention to the United States in the midst of the Cold War. In that context, any example of anti-Black violence was used as propaganda by the Soviets to embarrass the United States, especially with emerging nations. These days the U.S. doesn’t really have that same kind of powerful enemy and so open season on Black folks can continue without any repercussions.

As such, highly visible, audible, and palatable Black suffering doesn’t compel action to address or change the circumstances behind the victim’s tragic death. Instead, the broadcasting of these Black funerals are a source of entertainment and the ultimate injustice porn.

The sights and sounds of Black mourning, suffering and pain are a source of pleasure for White racists and those who benefit from White privilege. They are a reminder that Whites are insulated and immune to the injustices, terror, and violence that define the Black experience. These funerals underscore the vast differences between the Black and White experience of daily life, and tragic death.

The fact that we have to die under the right conditions to elicit sympathy is revealing. The fact that we publicly mourn in “respectable” ways to compel action is White supremacy itself. White America doesn’t need to televise the funerals of their tragic victims, because their murders compel outrage, underscoring that White lives and White deaths always matter. The mourning of the victims of 9/11, the Newtown shootings, and the Boston marathon bombings for example, were about mourning, memorializing, and preserving collective memory. The funerals of Black victims over the past few years have been about forgetting the roots and antecedents of racism.

Historical research shows that part of the emotional and performative nature of the Black funeral contains an element of racial tourism, with Black people and their rituals framed as “exotic” and “foreign,” thus rendering us as “other.” Watching televised funerals is a kind of voyeurism that enables non-Blacks to participate in Black culture without having to interact with Black people.

What Obama did last Friday was offer a safe vehicle in the performance of Blackness—as president, as a Christian, as forgiver-in-chief. Why can we celebrate him for singing but not for pointing out racism, even as White America gets outraged because he said “the N-word” in the course and context of an interview that touched on recent racist attacks? Even Obama participated in portraying Blackness as a cultural performance, as opposed to honoring and continuing its history of civil disobedience, fueled by the community rage at living under the conditions of racist violence

While his words importantly soothed the wounds of Black America, his place as “Eulogizer-in-Chief” and the funeral itself was ultimately about reassuring White America that the status quo remains firmly intact. This betrays the history of all-too many Black funerals, which have been catalysts for focused action and progressive change. Burying the dead uplifted our people, but only when we refused to wallow in grief and take decisive action to fight for those who gave their life for the cause.

We need Black churches to reclaim the roots in the struggle for Black freedom, to embrace these televised funerals as touchstones of emotional outpouring scattered along the long, winding road towards a just and truly equal society. Rather than reaffirming White privilege and Black respectability politics. These funerals must also hold White America accountable, demanding penance in the form of action in the dismantling of White supremacy.

In 1964, at the public memorial for three slain Freedom Riders, James Chaney, Mickey Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman, the Reverend Dave Dennis gave an angry eulogy at the public memorial: “The best thing we can do for Mr. Chaney, for Mickey Schwerner, for Andrew Goodman is stand up and demand our rights … Don’t just look at me and the people here and go back and say that you’ve been to a nice service, a lot of people came … anything like that … your work is just beginning … If you do go back home and sit down and take it, God damn your souls!”

Reverend Dennis’s words were a clarion call to action, accountability, and redemption; this was not about unconditional forgiveness. It is striking that the United States, the only industrialized Western nation that practices the death penalty, demands forgiveness from Black America without much less an apology or White America working to gain forgiveness. In the same week that a Boston judged sentenced the Boston bomber to death, amid widespread refusals of his apology, the nation has sat in awe of Black forgiveness instead of talking about how to turn these latest heinous murders into fuel for a radical movement.

The mourning we witnessed in Charleston should not only move Black people to develop strategies to protect our communities and preserve our lives, it should also inspire a rebirth of White activism in the tradition of John Brown, and Goodman and Schwerner and inspire White sacrifice and martyrdom for justice.

Because if Black people and our allies don’t start practicing legitimate forms of self-preservation and demanding justice, the revolution might not be televised—but the Black funeral sure as hell will.