'80s

I’m the Other Amanda P.

The writer shared only a name with Amanda Peterson when they attended the same high school. But the actress’s untimely death has inspired a new reflection on that dark and desperate year.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

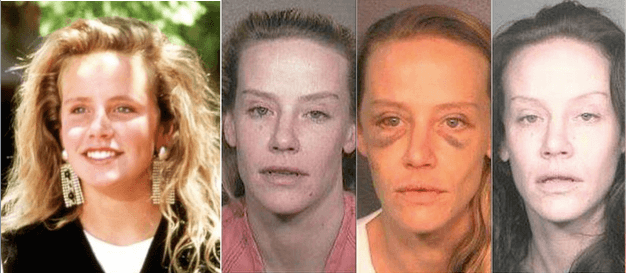

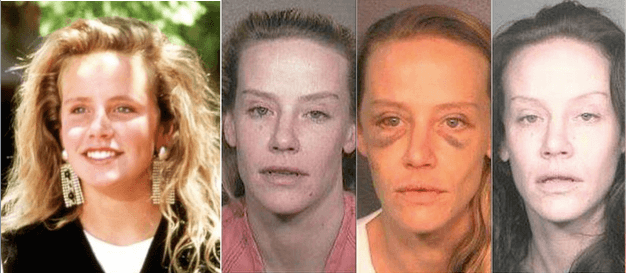

I never really knew Amanda Peterson—once a young Hollywood actress, who died unexpectedly on Sunday at the age of 43—but we did go to the same high school. In fall 1988, she was a senior, fresh off filming her award-winning television show, A Year in the Life. A year earlier, her lead role in Can’t Buy Me Love made her a star. I was a freshman just liberated from nine years at a tiny Christian school. As a newbie at this K-12 school where it seemed everyone knew everyone else, I was utterly obscure. The only thing she and I had in common was our names, and apparently our initials. At the time, my name was Amanda Polly. Later, I learned Amanda Peterson’s first name was really Phyllis, but that was not common knowledge at University High School.

What was common knowledge: Amanda Peterson’s dad was a renowned doctor in our town of 60,000. No one knew that my dad was a truck driver. When she was 9, Amanda Peterson had a role in my favorite childhood film, Annie. When I was 9, my mom sewed me a dress from a McCalls “Annie” pattern. When Amanda Peterson sang, her parents brought her to auditions; when Amanda Polly sang, her parents told her to stop. “Tomorrow” was my generation’s equivalent to “Let It Go.”

Amanda Peterson was the youngest. Whereas, I shared an unusual name with my older brother who had a bad reputation at my high school before I arrived. Amanda Peterson was famous for that white leather outfit/plot device in her film. By high school all of my clothes came from Kmart and garage sales.

During the nine months we were schoolmates, I never approached or spoke to the movie star. I saw her around the school, though, hobbling on crutches following a ski accident; laughing in the blue lobby with the other seniors; cheering with the crowd at a pep assembly. I saw Amanda Peterson shine, while I shrank into corners. For months, every day during my free period, I hid in the elementary-school girls’ room and cried until I could breathe again. My freshman year found me spiraling into a depression so deep I was planning my suicide and writing out my letters in pastel pens on notebook paper. That was the year I began to harm myself and become a serious binge-eater. It was also the year I discovered the stairwell behind the library that high-school kids never used and my little ledge where I ate lunch alone nearly every day.

For the first few weeks of school, before I discovered the stairwell, I had my lunch in the smaller lobby near the flagpole and the principal’s office. But the student-body president, a sweet guy named Ross, did his daily constitutional around the school and always stopped to say hello. Insecure and self-loathing, I fled his kindness like larvae flee the light. Our high school had a senior pantheon including Ross, state gymnastics champion Shannon, star athlete Jake whose dad married our young German teacher, and of course, starlet Amanda Peterson.

Ross and Shannon were both inexplicably kind to me. Jake was hilarious, the only senior in my freshmen German class. Perhaps he was there to get to know his future stepmom. I never met Amanda Peterson until the day she stepped behind me in the lunch line. Trapped as people filled in behind us, I wanted to flee. I refused to look at her face so I twitched and twirled the way nervous 14-year-old girls do as we faced the plastic trays and started down the food-serving area.

In spite of my efforts to hide in plain sight, I caught her brilliant smile in my peripheral vision and couldn’t help but turn toward her. “I really like your hair,” she said while looking straight at me. In that state of mind, I often struggled to accept any compliment without seeking some backhanded sarcasm encoded in the delivery. But Amanda was sincere, and as much as I hated my face, my body, my clothes, and almost everything else about myself, I did have nice hair.

“Thank you,” I whispered, and I think I smiled, which was something I rarely did then.

No, I did not know Amanda Peterson. I didn’t know she moved back to our hometown the year I got married and changed my last name. I did not know we lived in the same town for eight more years before I moved closer to work and graduate school. I had no idea she was living in the same apartment complex where my sister-in-law got her first place. It isn’t a bad place, but it is the kind of place where young people start out in life—not the kind of place movie stars go to die. Or maybe it is.

Maybe Amanda Peterson was never really a movie star. Maybe she was just a girl from Greeley, Colorado, like I was. Maybe she saw me in that lunch line and recognized my piercing loneliness because she was harboring loneliness of her own, but hid it better than I could. Maybe she went all over the world and just wanted to find “home.” Maybe she ached for that sense of belonging and constantly questioned herself without letting outsiders see.

Or maybe not. But if she did, if she nursed an aching soul, shattered by the confusion of life, then we had more in common than I ever knew. The one thing I do know about Amanda Peterson is that one day in 1989, when I was in my darkest place, she smiled at me and was kind.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.