Women are bombarded with ways WE can prevent sexual assault. But as Kate Harding shows us, in this exclusive excerpt from ‘Asking For It,’ there’s something inherently wrong with that.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

One summer night, while I was working on this book, my friend Molly, also an author, walked her greyhound over to my house for a writing date. Earlier that day, my husband had driven to Indianapolis on business, so Molly and I sat in my living room with our dogs and our laptops, drinking tea and clacking away for hours. It was lovely.

Around 11 p.m., Molly asked me for a lift home, per our usual routine when she visits my apartment, about a mile away from hers. But when I went to grab the car keys, they were missing. I checked all of my pockets and a couple of purses, to no avail.

Let’s cut straight to the Encyclopedia Brown reveal: Did you remember that my husband drove out of town? Because I sure hadn’t! And we only have one car.

So there Molly was, late at night, a 15-minute walk from home and saddled with a gangly, 65-pound dog who isn’t allowed to ride city buses (and who, it should be noted, would be utterly useless in the event of an attack). The mood in the room suddenly shifted from pleasant and companionable to “Oh, shit.”

I mean, we weren’t going to panic. Panicking would be stupid. Weak. An overreaction. You can’t live in fear! You must refuse to be a victim!

Molly was new to the neighborhood, but I’d lived there for eight years without incident. It was home, and I almost always felt comfortable walking around there. Still, during the month that this happened, 26 violent crimes were reported to police in the two-square mile area where she and I and about 55,000 other people lived. Two of those were criminal sexual assaults; one, a bona fide stranger-drags-a-woman-into-an-alley scenario. So if either one of us had remembered that my car was in another state before it got dark, there’s no question she would have left earlier. Who would plan to walk a mile through our neighborhood at 11 p.m.?

I mean, besides men.

“HELPFUL” TIPS

“Hi girls!” begins an email that made the rounds when forwarded safety tips from everybody’s credulous aunties were all the rage. More recently, the same information has spread on social media, with a link to a page claiming that what you’re about to read is the result of interviews with “a group of rapists and date rapists in prison.” Either way, the anonymous writer tells us she’s going to share some helpful rape avoidance tips.

From this document, we learn that women should avoid wearing their hair long, especially in grabbable ponytails (“The #1 thing men look for in a potential victim is hairstyle”). Clothing “that is easy to remove quickly” with scissors is also best avoided, so skip the overalls, gals! (Priceless advice if you were planning time travel to the early 1990s.) Also, no talking on your cell or rooting around in your purse in public—a distracted lady is just asking for some lurking criminal to crack her over the head and drag her off somewhere. You must be alert at all times!

Oh, and FYI:

The time of day men are most likely to attack and rape a woman is in the early morning, between 5 and 8:30 a.m.

The No. 1 place women are abducted from or attacked at is grocery store parking lots.

No. 2 is office parking lots and garages.

No. 3 is public restrooms.

If you’re thinking, Gosh, I never knew any of that before!, don’t feel bad: I’ve been reading about rape for 20 years, and I had never heard those things before the first time someone passed along the email. Probably because none of them is true.

Barbara Mikkelson, of the invaluable urban-legend–debunking website Snopes.com, researched every claim in that chain email and pronounced the whole thing “codswallop.” Noting that the message originated in 2000 with a St. Louis woman, who said it was her takeaway from a recent self-defense class, Mikkelson painstakingly punctures each assertion: No, long hair isn’t a risk factor for rape. No, rapists do not typically carry scissors. Most rapes occur between evening and dawn, actually. Parking lots and garages are only more likely to be the site of rapes or abductions if they’re empty and poorly lit; you can still go grocery shopping without fear of being attacked. Et cetera, et cetera.

“So, to sum up,” she writes, “is avoiding rape a matter of wearing your hair short and eschewing overalls? Hardly. And anyone who attempts to characterize it as such ought to be whomped over someone’s knee.”

My sentiments exactly.

Back in my living room at eleven p.m., I was furious at myself for having a mental lapse that put my friend in a shitty situation.

“I’ll call you a cab, tell them to send someone who doesn’t mind dogs, and I’ll pay,” I offered—but even as I said it, I was thinking of other possible scenarios: Molly could leave her dog overnight with me and grab any old cab home. She and the dog could both spend the night. She could go home in a cab, get her own car, and come back to pick up the dog. Or maybe one of my neighbors was still up and would let me borrow their car …

Running through this index of alternatives seemed completely normal to both of us. This is the stuff women are thinking about all the time, even as we brazenly strut through grocery store parking lots at eight in the morning, wearing overalls, with our hair in ponytails. How can I go about my life without risking my safety?

MARCHING INTO BATTLE

In a January 2013 op-ed for the Dallas Morning News, Robert Jensen, a University of Texas journalism professor and anti-violence activist, writes of talking with two freshman sorority pledges about the specter of sexual assault in the campus Greek system. The young women impatiently explain to him that they have a strategy to ensure it won’t be an issue for them: “We always go to those parties as a group, and we never leave anyone behind.”

Jensen points out to them that “leave no one behind” is the language of soldiers going into battle, not teenagers going to a party.

“I do not enjoy saying that, they do not enjoy hearing it, and we are all quiet for a moment,” he writes. “It is important, but not always easy, to recognize what is ‘normal’ in our culture.”

Ultimately, Molly insisted that she would be fine walking home—taking the most populated, best-lit route—and she was. That wasn’t a surprise to either of us. We both knew the whole time that she had a very good chance of making it home alive and unmolested. The problem wasn’t that we thought an assault was likely, but that as women, we’ve been taught never to rule out the possibility. We’ve been taught that it’s never safe to assume we’ll be perfectly fine, walking around our own neighborhoods after dark, like normal people.

This is why I have no patience for anyone who insists that women must learn self-defense moves and memorize lists of specious advice to prevent our own victimization. We’re already calculating risks and taking reasonable precautions every day. We don’t often talk about that in public, though, lest we be accused of letting fear control our lives, of being completely irrational about the relatively minor statistical risk of being attacked by a stranger.

It’s a maddening catch-22. If we get assaulted while walking alone in the dark, we’re told we should have used our heads and anticipated the danger. But if we’re honest about the amount of mental real estate we devote to anticipating danger, then we’re told we’re acting like crazy man-haters, jumping at shadows and tarring an entire gender with the brush that rightly belongs to a relatively small number of criminals.

No one will ever specify exactly how much worry is the right amount, the amount that will allow women to enjoy all of the freedoms typically afforded to North American adults in the 21st century, while reassuring judgmental strangers that we aren’t stupid and weren’t asking to be raped.

“BETTER SAFE THAN SORRY!”

Think back to that list of “don’t get raped” tips—and really think this time. Grocery-store parking lots are the number one place women get attacked? Are you kidding me? How did that ever sound logical to so many concerned relatives? It’s patently ridiculous.

But when you ask someone who’s just shared that list on Facebook, or suggested a self-defense class to a woman concerned about rapes in her neighborhood, they’re likely to respond with something like “Better safe than sorry!” Translation: “Even if what I’m telling you to remember is a pile of stinking horseshit, you should still engage in this ritualized expression of anxiety with me, because it makes me feel slightly better about things I can’t control. What’s so wrong with that?”

Well, nothing, if you’re just recommending simple, reasonable measures like locking doors, looking both ways before crossing the street, and carrying cash in purses or pockets, as opposed to walking around, waving it in the air, screaming, “I’m rich! I’m rich!” But there is something very wrong when you’re telling women (and only women) to keep their hair short, only dress in ways that no one could consider “provocative,” only dress in clothing that is difficult to cut off with scissors (so, Kevlar jeans, I guess?), and never use their phones or search through their purses in public.

There’s something wrong with expecting women to remember that they should always go for the groin, or the eyes, or the armpit, or the upper thigh, or the first two fingers (I am not making any of these up), and that it only takes five pounds of pressure to rip off a human ear, and if you hit someone’s nose with the palm of your hand and push up just right, you can drive the bone into their brain and kill them.

There’s something wrong with acting as though it’s perfectly reasonable to tell women never to drink to excess—and, when drinking to nonexcess, never to let their drinks out of their sight—and not to walk alone at night and definitely not to travel alone, and not to jog with earphones, and not to approach a stoplight without locking the car doors, and not to respond to the sound of a crying baby, and not to get into their cars without checking both the backseat and underneath the car first, and not to get in on the driver’s side if there’s a van parked next to it, and not to pull over for unmarked police cars until they’re in well-lit areas, and, and, and.

I just did that off the top of my head, by the way. A bunch of those recommendations are manifestly useless, but they are all in my brain, a full catalog of two and a half decades’ worth of “helpful tips.” Even the ones that are based in some sort of recognizable reality still ultimately send the same message: As a woman, you must live in fear and behave impeccably. If you fail at either charge, you will most likely be raped—maybe even murdered—and it will be at least partly your fault.

“Please forward this to any woman you know,” says the end of that email. “It’s simple stuff that could save her life.”

Actually, there’s nothing simple about it.

KANGAROO SIGNALS

In The Gift of Fear, his popular 1997 book on violent crime, security expert Gavin de Becker tells of an exercise he once did during a presentation at the Central Intelligence Agency. He informed his audience that a small but significant number of people per year are killed by angry kangaroos and then listed the three unmistakable signals a kangaroo will give before it attacks: a wide “smile,” compulsive pouch-checking, and a glance over its shoulder.

Only after audience members demonstrated that they’d memorized all three signals did he reveal that he’d made them all up—and in fact, he knows zilch about kangaroo behavior. Nevertheless, he predicted, everyone who witnessed that presentation would remember the fake indicators of an imminent kangaroo attack forever.

“In our lives,” writes de Becker, “we are constantly bombarded with kangaroo signals masquerading as knowledge.” The whole point of The Gift of Fear is that inaccurate information—along with denial about who’s most likely to be the perpetrator or victim of a crime—can interfere with our natural ability to intuit and react usefully to danger. Those handy “don’t get raped tips” that keep turning up on the internet like bad bitcoin are just more kangaroo turds for the pile that Western women are expected to carry around in our heads all the time.

By the time we finish high school, our brains are already filled with such rape-proofing basics as the appropriate skirt length for discouraging violent attacks (long); the number of alcohol units that can be consumed before one is thought to have invited sexual assault (one, tops); a list of acceptable neighborhoods to visit alone in daylight; another of acceptable neighborhoods to visit alone after dark (just kidding—there are none); and a set of rudimentary self-defense moves (“Solar plexus! Solar plexus!”).

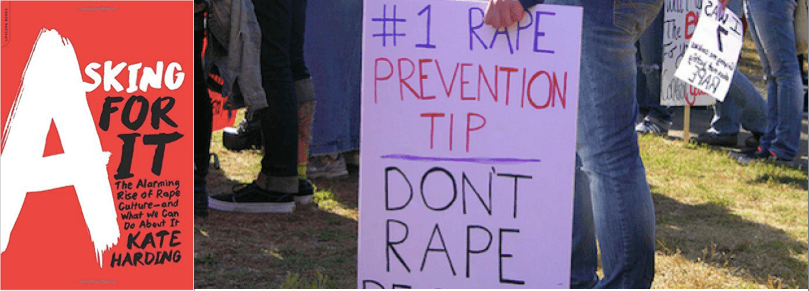

Excerpted from ASKING FOR IT: The Alarming Rise of Rape Culture—And What We Can Do About It, by Kate Harding (Da Capo Lifelong Books). Click to buy it here.

Photo by Flickr user Alan