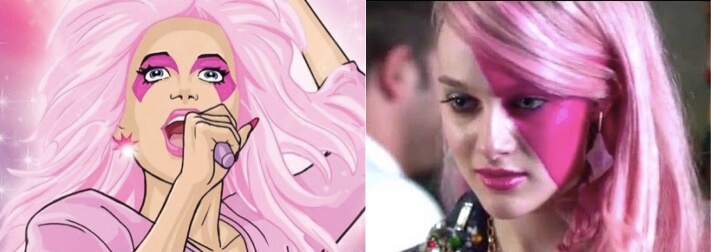

The inspiration for the '80s cartoon glam-pop pink-haired heroine—and now a movie 'Jem and the Holograms'—Jemi is everything you'd ever want her to be. Except a Jem fan.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

The Saturday morning cartoons of my childhood—one of the few times I had unrestricted access to the family TV—were composed of a landscape of rainbow bears, pastel ponies, perky blue elves, and singing chipmunks. As gloriously psychedelic as that all sounds, these shows didn’t feature a lot of actual girls. At least, not ones that I could idolize. Smurfette was a drippy bore. Strawberry Shortcake was a treacly goody-two-shoes in bonnets that a Laura Ingalls Wilder fetishist would’ve rejected as dowdy.

And then came the show Jem and the Holograms.

Everything about Jem, the alter-ego of orphan Jerrica Benton, rocked: The waves of pink hair spilling down to her waist. The KISS-inspired slashes of pink eyeshadow. The fashions that veered from Jessica McClintock prom dresses to fluorescent Cyndi Lauper fishnets to Sgt. Pepper-style military jackets—sometimes in a single outfit. Jem didn’t just dress the part, but actually fronted a glam-pop band with her three sisters (two foster, one bio) called—yes, the Holograms—while running the record label that her father founded. Although Starlight Music was in perpetual danger of being snatched away by conniving dudes, Jem always outfoxed them. Just like she outsmarted rival girl group The Misfits (a whole other story). And drove in the Indy 500, met Mozart, and hung out with the Yeti. Kinda makes running a foster home seem tame, but Jem found time to do that too. One more thing: She wore magic, star-shaped earrings that allowed her to access Synergy, a super-computer capable of instantaneously creating ultrarealistic holograms to fulfill any need: cars, castles, landscapes, people, you name it. Like so many literary heroes, Jem was an orphan, but instead of pickpocket gangs or wizarding schools, she lived a truly outrageous teenage dream of glamour, glitter, fashion, and fame.

Jem and the Holograms ran for three seasons, from 1985 to 1988. The cartoon was middling stuff but it drew a devoted following. Hollywood’s unceasing attempts to strip-mine 1980s nostalgia means there’s a live-action version of Jem and the Holograms, which hits theaters on Friday, October 23. To be honest, the movie itself looks … bad, but the story of how the original cartoon came to the screen does not.

Because it has given me an occasion to be sitting across from a woman named Jemi Armstrong in a Starbucks in Venice, California. Admittedly, she seems nervous. I am trying to mask my excitement—I’ve been unreasonably ecstatic since learning, a couple months earlier, that there is a “real Jem,” a living woman who was the inspiration for the fictional rock star.

“I’ve got to be honest with you,” she says, “I was really hesitant to meet you because I thought this is just weird.”

She doesn’t pull up in a hot pink Bentley while playing a keytar. Jemi has walked over from the home she shares with her husband and their two rescue dogs, a Maltese and a Chihuahua-Jack Russell mix. Jemi, now 57, is a fashion illustrator, a professor who teaches at Santa Monica College, and an author of seven books, mostly about the fashion industry. She is petite and perky, and still loves pink, so much so that the inside of her house is painted a shade of deep fuchsia known as Schiaparelli Pink. She still has long, blonde hair that she has been dying pink streaks in, on and off, for decades. “Now I think I’m going to stay away from that. I don’t want to exploit that,” she says. By that, she means the mild hoopla that occasionally crops up around Jem.

In the 1980s, Jemi—that’s her given name—was something of a Hollywood wild child. “I think anybody who was in Hollywood in the ’80s was probably doing stuff they shouldn’t have been doing. That’s just the way it is. If you were hanging out in Hollywood or New York in the ’80s, there were a lot of places for a young kid to get into trouble, let’s just put it that way. Fortunately we all grow up and get wise.” She won’t reveal more about it than that. “I’d like to keep the Professor Armstrong patina of respectability while I can.”

The child of two old-school garmentos, Jemi grew up mostly in Los Angeles but spent time in New York and Europe with her parents. “When I was 17, my mom basically told me that if you’re going to be interesting, you better go somewhere,” Jemi says. She was shipped off to Europe with $600 and a backpack. “I was there for about a year, just hitchhiking all over with a girlfriend. My mom told me it was going to make me a lot more interesting person. When I came home, she was absolutely right. I felt a curiosity toward things that my peers didn’t, let’s put it that way.”

By the early ’80s, Jemi had either graduated from FIDM or was about to. She was considering a move to London but her father, who was momentarily flush, set her up in a “really nice” apartment in Hollywood, near the Magic Castle. She was hanging out with animators and commercial artists, hustling sketching and painting work. Designing T-shirts for rock bands, painting roller skates for people who skated down Sunset Boulevard.

Jemi also dabbled in jewelry design. “I was in New York with a friend and I got an idea for these earrings. We found a pair of these tin stars, drilled some holes in them, and somebody managed to put a little tiny battery in the back so they blinked. You’ve got to remember we lived in a very low-tech era. Anything that was battery operated was cool.”

Her clothes were de rigueur for the era: “I remember the fishnets. I remember pink pumps. I looked like Cyndi Lauper. We all did.”

As for her hair, it was down to her waist and streaked with pink. “People probably can’t grasp this today because everybody has pink hair but nobody had pink hair then. Absolutely nobody had pink hair. My parents thought it was the end of the world. I would have been better off coming home pregnant. I probably looked like a freak to some people, but the animators I hung out with at the time thought, oh, this is really cool. I’m assuming that’s why Paul thought it was an inspiration for a cartoon.”

Jemi can’t remember where she met Paul, possibly at an art supply store or at a party thrown by a friend who worked for Heavy Metal magazine. “It’s all blurry. It was the ‘80s,” she says. They hung out a handful of times, maybe even went on a few dates. “The thing that I remember is that he was blonde. He was short and stubby. I wasn’t really attracted to him. He had an office at Universal. He was here, he said, doing character development on a freelance job for Hasbro, Hanna-Barbera. I went up to his office and hung out with him and some other animators. This went on over a couple of months and then he went back to Australia.” Jemi never saw him again.

Months later, the Jem doll hit stores. “When I saw the doll with the pink hair and the flashing stars, I knew it was me,” Jemi says. “The doll came out before the actual TV show. I remember because I ran to the Sears Roebuck on Laurel Canyon and I saw like five of them in the store. I was horrified. I brought them home and threw them in the closet and hid them.”

Developed by Marvel Productions, Hasbro, and Sunbow Productions, an animation studio spawned by an ad agency, Jem and the Holograms was, at its most basic, a way to sell toys. (Same deal with the G.I. Joe and The Transformers cartoons, which this trio of companies also produced.) Jem’s creator was Christy Marx, a celebrated writer of animation, video games, comic books, and more. Before the cartoon (or the doll) debuted, Jem went through several iterations. Paul was just one unnamed “freelance character development storyboard animator guy” brought on to help flesh out the character. “He was here, I guess, troubleshooting because in the beginning it went through a lot of phases,” Jemi says. According to her, in one of the early stages, Jem was a fashion designer named M.

“I knew it was me because one thing I remember Paul asked me was, ‘Why don’t you spell your name with a G?’ It’s because my mom spelled it with a J. Nobody believed me but that was my real name,” Jemi says.

Jem mostly ignored the cartoon when it first came out. “I know I was the inspiration for it, but I have never, and I never will, try to make a fuss or profit from it in any way. It’s always been more of this weird sort of thing that I didn’t think anybody cared about,” she says. Occasionally her husband jokes about it or one of her students makes the connection and hums the Jem theme song to tease her. A few years ago, while leading two dozen students on a tour of France, a friend brought up the subject. “And these little girls in French start going, “Jem, Jem!” and pointing at me. And I’m thinking, ‘Do I know you?’ It became a big deal in this little store in the middle of the Loire Valley.”

For a long time, Jemi saw Jem as silly and frivolous. To be fair, she’s not wrong. Jem and the Holograms was a trifling cartoon targeted at tween girls. But Jem (Jerrica if you prefer) was cooler than almost any other cartoon heroine. (Looking at you, Josie.) In addition to being a rock star, an entrepreneur, and a do-gooder, she ran her own show and never settled for being anyone’s arm candy. She was a relentlessly positive teen prodigy who ignored and outsmarted the older, more experienced music industry Svengalis (read: men) who tried to exploit her. Picture Jem as a proto-Taylor Swift. I explain my take on the show to Jemi and when we chat for our formal interview a couple months later, she tells me she’s thought about what I said. “I really did a 180,” Jemi says. “It went from being this stupid thing from this guy I dated to being, like, maybe some young girl is somewhat empowered by it in some small little way. And that completely changed my mind.”

Jemi asks what I think of the trailer for the new Jem movie. I make a face, I say. I don’t have high expectations for it because, as I tell her, it lacks the charm and kick-ass sensibility of the original cartoon. Besides, how do you not cast TayTay as Jem?

“Thank you,” Jemi says. “Me too. It’s kind of gross. I mean, it has nothing to do with the original characters. Maybe we’ll both be proved wrong.”

The Jem dolls that she shoved away in her closet have long since been lost or given away, something Jemi now regrets. But for the longest time, until maybe a decade ago, she hung onto the earrings. Alas, they had no special powers. “They were just really cheap looking little silver stars with those flat LED batteries,” Jemi says. The magic lay elsewhere, in an improbable cartoon heroine who continues to sparkle with her assertive rose-tinted charm.