Discovering the work of Mary Gaitskill was like a revelation for the writer. Which is what makes her disappointment with Gaitskill's new novel, 'The Mare,' so hard for her to fathom.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

I came to Mary Gaitskill in my early twenties after a teacher recommended her debut short story collection Bad Behavior, for its “dark potency.” In those pages, I found power, but not in darkness: The work was like streetlight winking through shards of broken glass, illuminating the casual brutality and bruised tenderness of life as I’d known it. Her characters, like me and so many of my friends, wandered that liminal terrain between late adolescence and early adulthood; a landscape that can feel lonesome and arid, yet simultaneously waterlogged with choices: the kind of choices that we’re told, by friends, parents, ex-lovers, are essential and transformative—what we’ll do for a living (a “respectable,” boast-worthy living, that is) and who we’ll become—but still feel as tedious as choosing between whole-grain and multi-grain bread.

I would read passages from those stories aloud to my friends, and we would marvel at how she had translated the tattoos of our pulses onto the page. In “Trying to Be,” a woman who has moved to New York City to impress a status-obsessed ex searches for something approaching authenticity in a scene full of fashionable schemers: “Stephanie wandered from conversation to conversation, having an almost panicky feeling that although there were nice, interesting people in the room, the situation, for all its seeming friendliness and ease, precluded her from connecting with the nice and interesting parts of them. She tried to figure out why this was and could not, beyond the sense that the conversations around her were opening and closing according to subtle but definite rules that no one had told her about.” Gaitskill didn’t just articulate a kind of loneliness rooted in a kind of awkwardness that would’ve been rendered as cutesy or endearing in a film (as the cinematic adaptation of her short story “Secretary” proves), but in real life felt awful and irredeemable—she gave it dignity.

Her second short-story collection, and third book, Because They Wanted To, carried me during the listless tilt into my thirties; this collection made poetry of regret, featuring characters who have made their choices and found their places—only to kick and flail inside the cellophane jail cells of day jobs and lousy lays and aging bodies: “Her thin shoulder in its T-shirt was exposed; it looked both winsome and pathetic … This would be cute, he thought, if they were anywhere between eighteen and twenty-five. But they were both over thirty; they had lines under their eyes, stains under their teeth, faces that more and more showed their essential confused mildness.” Because They Wanted To is a burn and a balm; it is peopled with the broken-hearted and the disheartened, and yet, some of these characters possess a fortitude that, given their circumstances, feels poignant, even inspiring: “It was still difficult for Margot to sit down to eat by herself. Still, she was determined to do it … it made her feel like a tenacious animal, burrowing a home in hard, dry soil.” There have been many nights where, as my Facebook feed fills with wedding pictures and I prepare my nightly meals for one, I hold the words “like a tenacious animal” in my head like a talisman.

There is no writer alive, in my opinion, who can quite match Gaitskill’s prose at its peak: Her sentences are like slow molasses, rich and dense and demanding to be chewed and tongued and savored in a visceral, tactile way. But the prose is not just beautiful, it creates a profound interiority that is, perhaps, the true hallmark of Gaitskill’s best work. This interiority propels what is arguably her greatest book, the book that crystallized my desire to become a writer, because if I could even approach the threshold of everything she’d accomplished in that book—the characters that haunt you, the immaculate language moving the story and establishing the scope—I would still have achieved something great, the National Book Award–nominated Veronica. A young model’s gradual heartbreak and maturation, and her complicated friendship with the titular character, a brass, kitschy middle-aged office worker, becomes an excavation of the female body as a many-chambered cave of pleasure and pain: “Then he jumped on me. I say ‘jumped’ because he was quick, but he wasn’t rough. He was strong and excessive, like certain sweet tastes—like grocery pie. But he was also precise. It was so good that when it was over, I felt torn open. Being torn open felt like love to me; I thought it must have felt the same to him.”

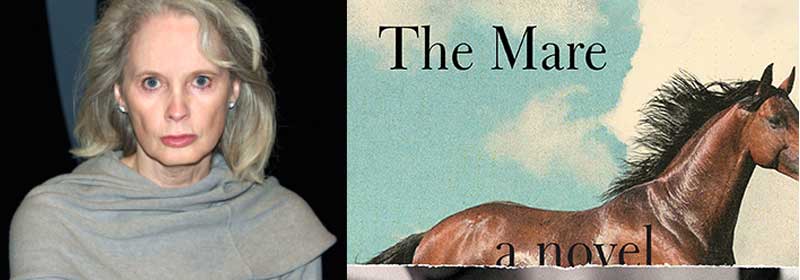

When I’d learned that Gaitskill’s new novel, The Mare, would focus on motherhood, I was intrigued; though I’ve long decided that parenting is not for me, I’ll be turning 34 next year, and, at times, I am unexpectedly curious, even wistful, about the ghost ship that did not carry me. I was excited to see Gaitskill apply her diamond-sharp, diamond-bright powers of observation to a new kind of longing. There is, of course, great peril in weighing the merit of any book against one’s original hopes for it. And perhaps it’s unfair, or even flat-out wrong, to expect any artist—but especially an artist whose work has nourished us—to keep adding the same old eye-of-newt into her cauldron, to keep incanting the same words. And yet, The Mare is so confounding to me: Parts of it spin that familiar spell of intimacy, but, by and large, it lacks the depth and complexity of character and language that breathe fire into the earlier works.

The Mare begins as the twinned narrative of Velveteen “Velvet” Vargas, a young Dominican girl living New York City squalor with her volatile mother and little brother, and Ginger, a thwarted artist and ex-addict now living cozily upstate with her professor husband. Ginger, haunted by the death of her sister and her own chaotic youth, feels an earthquake of maternal urge; she and her husband, Paul, sign up for the Fresh Air Fund (which brings inner city youth upstate for bucolic country summers), to steady the ground and (hopefully) plant something lasting. Though Ginger desperately wants to be a surrogate mother to the lonely, abused girl, Velvet finds her heart in the horses at the barn near Ginger and Paul’s property—specifically in Fugly Girl, the mare with the scarred muzzle, the beast of burden who has also borne the brunt of someone else’s anger. Early chapters, and the early days of Velvet and Ginger, retain that immersive interiority—but as the novel, and the relationship, stretches on in years, it becomes hollower, shallower. Actions that should be motivated by a deep sense of character happen, at times, too randomly, clearly in service to a plot that strains to sustain itself.

At various points, Gaitskill opens the book to include the perspectives of other characters. However, the book’s most affecting arc belongs to Velvet, whose story feels universal and yet uniquely her own: She craves acceptance from a mother who is incapable of giving her what she needs; experiences the first stirrings of attraction with a charismatic older boy who loves her, then loves her not; and finds, in her bond with Fugly Girl (whom she renames Fiery Girl), that she is not the stupid, ugly girl her mother beats, but a talented young woman possessed of great power and spirit: “I felt her muscles, her blood. I felt her… This was my place. No one would ever be in this place but me and my horse. No man, not even children; they would never come here with me. This place was only for me and my mare.” Velvet’s story features moments of genuine transcendence and discovery—which makes the drag and stasis of Ginger’s plotline all the more glaringly apparent.

Ginger is more a collection of tics and traits than a woman in the flesh. In her first point-of-view chapters, we see her sifting through the embers of old grief and withered ambition, remembering her art as “a place of deep joy where, when I could get to it, was like tuning into a radio frequency that was sacred to me.” Ginger’s attachment to Velvet soon becomes that radio frequency, and that frequency picks up a dark static—what starts as a desire to nurture gradually becomes an obsession, and not just an obsession with Velvet herself, but with how the people around her—specifically Paul’s patrician ex-wife—view her. As this happens, Ginger’s voice is washed bare of all of Gaitskill’s painterly nuance; she begins to narrate her feelings at us with a hammering bluntness that turns a tin sculpture of a story into a flat sheet: “Judging me like I’m an ignorant racist or just a childless neurotic fool … Naturally her mother didn’t want her to compete [in the horse show] because of course it would be threatening to her to see her daughter do something she herself could never do, something only I could offer her.” This propensity for over-articulating actions and reactions is like treading water narratively—moving constantly without finding shore. I longed for the earlier, more contemplative Gaitskill, the author who would have made Ginger’s radio frequency crackle and sing, who would have coaxed out the true pathos of feeling called to create and being unable to.

I don’t have the right to insist that The Mare be Veronica, or the short-story collections that sustained me through the loneliest times of my life. And perhaps it’s unfair to judge the book as it is—broader, and more accessible—against what I wanted it to be—a deep plunge into the fiercely pumping valves of some dark heart with the letters M-O-M tattooed on it in tinsel. Gaitskill does seek to skewer the ideals of sainted motherhood through Ginger’s relapse and through Velvet’s mother, Silvia, who wields belt and shoe and the flat of her hand to beat the bitterness of her hardscrabble, hand-to-mouth life out upon her daughter’s body. She is the only character whose chapter headings don’t include her first name, but the more auspicious, and distancing “Mrs. Vargas,” and among the novel’s carousel of voices, hers is the farthest and the dimmest.

Many of Mrs. Vargas’s chapters are filled with a hallucinatory piling-on of images (most of these involving bodies crammed into a subway) that are deliciously lyrical, yet don’t truly orient us in the character’s history or headspace. Two direct flashbacks to her past—a moment from her girlhood in the Dominican Republic, and how she came upon Velveteen’s name—are so dream-like they become inscrutably opaque. Without greater clarity, Mrs. Vargas’s violence feels too random, and not at all organic to her as a person; it is the sudden flux in atmosphere that happens whenever a storm might serve the plot. Even within the context of being bitter and poor, Mrs. Vargas would appear to have no clear motivations (however upsetting they may be) for beating her daughter and refusing to let her ride, only to acquiesce (and then refuse again). Both Ginger and Paul refer to Mrs. Vargas as “a tank” and unfortunately, the novel affirms this detached, dehumanized view of her.

In a recent interview with The Millions, Gaitskill admitted that Silvia was the toughest character for her to portray. “At first I thought, I can’t do this. I can’t understand her well enough and I won’t do her justice … because she really was the character who I had the most difficulty … Not understanding her on a really basic level … I don’t know what it would be like to be her.” And so it bears out, because we meet in the pages of The Mare, less a fully realized woman who is painfully inflicting her own heartbreak on the child who reminds her of all her failings and all she hoped to be, and instead, more of a hot-headed, heart-hearted caricature. In that same interview, Gaitskill describes feeling compelled to share Mrs. Vargas’s story, and “[hoping] I did her justice.” I wish Gaitskill had done more than just hope—here is a writer who can find humanity and pathos in even the most troubling, repugnant characters (such as the gang rapist in her iconic story, “The Girl on the Plane”).

When the same friends I called to read passage after rapturous passage of Gaitskill’s prose ask me about her new novel, I say that I’m stunned—but not in the good way, the old way, the way that felt like unexpectedly spotting a cherished friend in the subway at rush hour. Gaitskill’s earlier books will always be those friends, embracing me with vigor and warmth as the world rumbles and groans on around us. But henever a favorite author disappoints us, it creates an inexplicable, perhaps unreasonable hurt. As readers, we have so many choices, and no particular writer truly owes us anything. And yet, I can’t help it; I feel a little stung with loss. But I will still come back for Gaitskill’s next book, hoping for a flash of magic.