It is all too easy to roll your eyes at the lawsuit between two entities whom many would characterize as “sleazy”—an ostentatious professional wrestler–TV personality who was unwittingly filmed shtupping a married woman (not his wife) and a clickbait-starved online gossip site who posted the video. But there’s a reason, beyond prurient curiosity, that we should be paying attention.

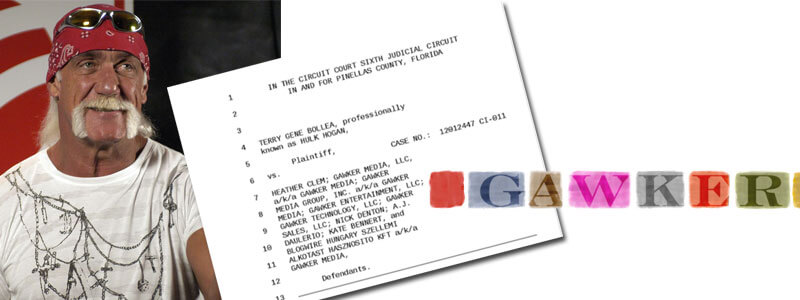

Some readers may be familiar with this story, but to bring those who aren’t up to speed: In 2012, Gawker posted a video of Hulk Hogan (real name Terry Bollea) having sex with a woman who was married to another man. Hogan is suing parent company Gawker Media—an online media group that includes Deadspin, Jezebel, Lifehacker, and Gawker itself—for invasion of privacy.

Hogan says that he didn’t know he was being filmed, nor did he release the video to the public. Gawker concedes that they received the video from an anonymous source. Indeed, the husband of the woman Hogan was having sex with agrees that the video had been in his possession before it was, as he claims, “stolen.” Hogan is seeking $100 million in damages from Gawker.

One of our major modern-day press freedoms came around with the U.S. Supreme Court case

New York Times v. Sullivan (1964), which arose during the height of the civil-rights movement. It protected the New York Times against a libel suit brought by the Montgomery, Alabama, Public Safety commissioner, L. B. Sullivan. Sullivan sued over an advertisement the Times published in support of Martin Luther King Jr. Sullivan quibbled with small details in the advertisement, for example, the number of times King had been arrested by Alabama police.

In a 9-0 opinion in favor of the newspaper, the Supreme Court established that “the First Amendment protects the publication of all statements, even false ones, about the conduct of public officials except when statements are made with actual malice.” “Actual malice” is a high standard to meet, and so most plaintiffs’ cases fail when the plaintiffs are public figures.

But #HulkvsGawk is hardly a case of such high moral questions as Sullivan.

Or is it?

Gawker would like us to think that Hogan’s case doesn’t have a leg to stand on because he’s a public figure. Under the law since Sullivan, public figures like Hogan have a really hard time winning lawsuits against the press for invasion of privacy because, just like they do for defamation, public figures must show actual malice. And, as anyone who watches television knows, Hogan has done all he can, through reality TV shows such as “Hogan Knows Best,” to thrust himself in the public eye over the past few decades. Without question, he is a public figure.

And no matter how you may feel about the quality of the news Gawker publishes, they are, in fact, a news organization. But today’s new-media landscape makes it difficult to discern what is and isn’t news. A website that today might seem like a troll basement blog might tomorrow be a

Breitbart,

The Drudge Report, or

TMZ. Whatever you might think of these particular sites, they have a degree of legitimacy and should therefore be protected by the First Amendment’s freedom of the press.

Then there’s the issue of posting the sex tape itself.

This isn’t an issue of being for or against pornography or sex or sex work. I’m not anti-pornography. I’m super-duper pro-sex-worker. I’m not anti-sex-tape. If a couple wants to post their sex-tape on the internet, fantastic. This is about consent. Consenting to be filmed. Consenting to release that footage to the public.

I can only glean here from what has been revealed in Hogan’s case that the sex-tape was likely filmed by a jealous husband without Hogan’s knowledge. And I would guess it was also likely released by the jealous husband to one of the biggest celebrity gossip sites on the internet. And so here we have two victims of what arguably qualifies as “revenge porn”—the woman who was having an extramarital affair, and Hogan, the man with whom she was engaged in the affair.

What is

revenge porn? Google, in a

public statement about how it is voluntarily removing revenge porn from its search engine, defined it this way: “an ex-partner seeking to publicly humiliate a person by posting private images of them.” Revenge porn sites are the post-apocalyptic garbage of the internet. It can be incredibly harmful to its victims, yet only about half of U.S. states have anti-revenge porn laws.

As the

New York Times,

Vox, and others have mentioned, this case would appear to reek of revenge porn—and that’s what most concerns the lawyer in me.

Gawker, in its arguments, sounds like the purveyor of revenge porn. They want the right to publish non-consensually recorded sex acts simply because a person is a public figure. If Gawker wins, it might set dangerous precedent in the revenge porn arena.

Gawker has argued that Hogan, by discussing his sex life and the existence of this sex-tape in public, he has forfeited his right to sue Gawker for publishing the sex-tape itself. According to Vox, “Gawker plans to argue in return that as a celebrity who frequently raises details of his own sex life—including the video’s existence—Hogan has created sufficient public interest around the topic to merit the video’s publication.”

Gawker’s defense is basically this: because Hogan discussed his sex life in public, he deserved what happened. He “created interest.” He made the public want to see the sex-tape.

Gawker sounds an awful lot like any other victim-blamer.

That Hogan is a public figure only means that his revenge porn was published on Gawker, rather than on a revenge porn site that Google refuses to index.

Yes, Hulk Hogan’s public stature makes it difficult to view him as a “victim.” The tendency is to see that he brought this on himself. But substitute nearly any other human, and Gawker looks really, really bad here. If that video were published on a revenge porn site it would already be de-indexed by Google or taken down completely.

If Hogan wins, media organizations that trade in news about public figures may have to dramatically change their practices. Hogan is, after all, a public figure. Had Gawker only published a verbal description of the sex-tape in question, it is highly likely this suit would have been dismissed a long time ago. That’s the legal standard that media organizations count on: They can question public figures and push boundaries because it’s their job to do so—even when treading the line of accuracy—so long as they’re not acting maliciously.

But Gawker published footage of a person doing something incredibly private—footage recorded without his knowledge—and released that footage to the public without his permission. And the footage was likely sent to Gawker by a husband bent on revenge. If this is a revenge porn situation, should it be treated differently than a typical public figure invasion of privacy or defamation case? Should it be treated as a revenge porn case?

I think it should be.

There is a way to slice a ruling in Hogan’s favor thinly enough that it can protect both revenge porn victims and media entities. How’s this for a rule: Media organizations cannot publish non-consensual sexual footage—revenge porn—just the same as anyone else. The law is capable of working with a scalpel, and it should in this case.

Gawker got it wrong when it decided to publish revenge porn. But the public figure rule needs to stay in place. We need to protect the right of media organizations to question public figures.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.

Support Dame Today