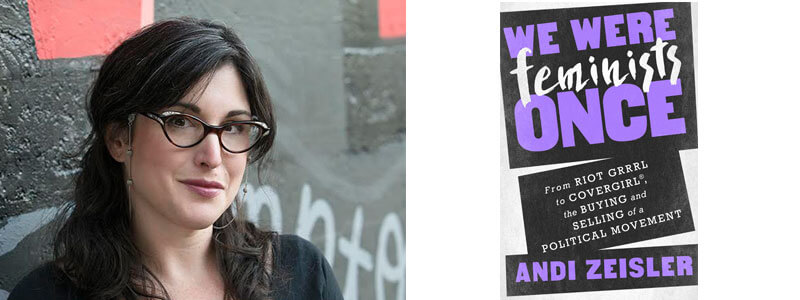

In this brilliant exclusive excerpt from WE WERE FEMINISTS ONCE, author Andi Zeisler describes the cynical cultural climate of the 1990s that set the stage for so-called “post-feminism."

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Chronologically speaking, American third-wave feminists (I include myself in this group) were the symbolic children—if not the actual children—of a generation that in large part was politicized during the 1960s and 70s. Between national water and oil shortages, an overseas hostage crisis, “stagflation,” drug epidemics, an ever-looming threat of nuclear war, Son of Sam, and a vogue in unnatural fibers, the world in which we grew up was not exactly utopia. But pop culture with a social conscience: that we had. We were the beneficiaries of Title IX who watched Billie Jean King thump Bobby Riggs in the “Battle of the Sexes.” We knew every word of Free to Be You and Me, the soundtrack of a liberal-leaning childhood on which burly football star-needlepoint enthusiast Rosey Grier assured us that “It’s Alright To Cry” and Carol Channing’s “Housework” dismantled the advertising industry. We had the TV empire of Norman Lear, whose slate of topical, race- and class-conscious sitcoms lobbed issues like abortion, racism, white flight, and rape directly toward the nation’s Barcaloungers. Even toys were sort of enlightened: Elizabeth Sweet, a doctoral candidate at University of California–Davis, recently studied changes in Sears-catalog toy ads, and found that 1975 was the peak of gender-neutral toy marketing, with 70 percent of such ads making no overtures to gender at all and a good number of them consciously “def[ying] gender stereotypes by showing girls building and playing airplane captain, and boys cooking in the kitchen.”

We didn’t talk about social-justice movements in elementary school, but almost every part of our lives was shaped in some way by feminist and civil-rights activism, and plenty of us were lucky enough not to know just how lucky we were. Regardless of whether the mothers, fathers, grandparents, and guardians of America aligned themselves with women’s liberation as a political movement, a social consciousness had been established in the mainstream, solidified with legislation, and disseminated by media and pop culture. But as we grew, so did a creeping sense that maybe this equality stuff had been overpromised. The elementary-school teachers who scolded girls for playing “too rough” with boys in schoolyard kickball or tag became the high-school counselors who expressed doubt that girls could “really understand” physics. And all the while, the double standards for dating and sex remained unyielding.

Susan Sturm, a professor at Columbia University’s law school, uses the term “second-generation bias” to describe the sexism and racism tucked unassumingly away in schools, corporations, and other institutions that have supposedly been “fixed” by the gains of women’s and civil-rights movements. If “first-generation” bias took the form of explicit barriers to autonomy and achievement—college departments that refused to admit women and racial minorities, illegal contraception, gender- and race-segregated want ads—the second-generation form was far more subtle and likely to be explained and internalized as an individual matter. The insidiousness of second-generation gender bias—informal exclusion, lack of mentors and role models, fear of conforming to stereotypes—colluded with the ideological spread of neoliberalism recast institutional inequity as mere personal challenges.

If women now had the right to do most everything a man could do, went the logic, then any obstacles or failures weren’t systemic, they were individual and could be remedied by simply being better, faster, stronger, wealthier. This was the fertile environment in which a new iteration of post-feminism—call it “I’m-not-a-feminist but” feminism—was taking root in opposition to the third wave, and, not coincidentally, catching the attention of mainstream media and pop culture.

By the early 1990s, the political landscape was pocked with a bitter conventional wisdom that feminism had, if not outlived its usefulness, then certainly aided the creation of a culture of victimhood that infantilized girls and women, demonized men, and made sexual dynamics a minefield. Neoliberalism was curdling into an I’ve-got-mine-so-fuck-you attitude toward social responsibility, and there was a whole new corner of American media intent on mourning a time when nobody was forced to acknowledge things like inequality, institutional bias, or offensive language. “Political correctness” was referenced with barely hidden derision, as though it was just too exhausting for people to have to think about what they said or how they said it. “THOUGHT POLICE” boomed a 1990 cover story in Newsweek, adding in its subtitle, “There’s a ‘politically correct’ way to talk about race, sex, and ideas. Is this the New Enlightenment—or the New McCarthyism?” (Cue the portentous music.)

The article itself detailed efforts on college campuses around the U.S. to broaden curriculums and increase tolerance, but the ostentatious quotation marks around terms like “diversity” and “multiculturalism” made clear that the magazine saw those things as pointless, oversensitive claptrap. It was here that the terms of post-feminism began to shift a bit, from exaggerated reports of feminism’s demise to the realm of what Ariel Levy would describe in her 2005 book Female Chauvinist Pigs as “loophole women”—those who believed themselves so evolved they had no need for the feminist fun police and their starchy, sexless ideology. Their ideological leader was the grandstanding theorist Camille Paglia, whose early-’90s trio of books—Sexual Personae; Sex, Art, and American Culture; and Vamps and Tramps—needled movement feminist gospel with all the glee of a teenage boy mooning a church picnic.

For Paglia, the feminist movement’s fatal misstep was that it wanted to block off the male vitality that she claimed was naturally expressed in rape: “Feminism with its solemn Carrie Nation repressiveness cannot see what is for men the eroticism or fun element in rage, especially the wild, infectious delirium of gang rape.” (Yes, well, our bad, I guess.) She found women in general to be lacking, in part because they just don’t pee with as much élan as men: “Male urination really is kind of an accomplishment, an arc of transcendence. A woman merely waters the ground she stands on.”

Though Paglia proclaimed herself, along with Madonna, to be culture’s staunchest feminist, she discredited any feminism other than her own as out-of-date victimology, sneering that the movement “has become a catch-all vegetable drawer where bunches of clingy sob sisters can store their moldy neuroses.” As the decade went on, the Paglia school grew to include a handful of fellow loophole women who made the mainstream media’s job of trash-talking feminism a lot easier. Katie Roiphe, daughter of second-wave feminist author Anne Roiphe, made a media splash in 1993, when The Morning After: Sex, Fear, and Feminism on Campus was published. Roiphe had been covering what she skeptically called “date rape hysteria” for a year or so before the book was published; in it, she asserted that the rise of acquaintance-rape cases were the result of women primed by feminism to see themselves as victims. (Rather than, say, the outcome of no longer referring to a sexual assault as a “bad date,” as mothers like hers and mine did.) Though her thesis was little more than “I don’t know anyone who’s been raped, so it’s probably not a thing,” the 25-year-old Roiphe, like Paglia, fancied herself to be offering a brave corrective to doctrinaire second-wave ideas of women as perpetual prey.

Elsewhere in 1993, Naomi Wolf ’s Fire With Fire: The New Female Power and How It Will Define the 21st Century defined hard-charging “power feminism” as an alternative to—you guessed it—“victim feminism.” And though Rene Denfield’s 1995 book The New Victorians: A Young Woman’s Challenge to the Old Feminist Order contained some important challenges to liberal feminism’s erasure of nonwhite, non–middle-class women, it mostly focused on caricaturing feminists as man-hating, goddess-worshipping wing nuts. What all these authors had in common, both with each other and with the cultural climate, was the belief that no value remained in collective action, that having the ability to transcend gender inequality was a project not of feminism, but of individual women who simply willed themselves to do so. As with post-feminism, glomming onto the irresistible image of the new guard flipping off the old allowed mainstream media to sidestep the challenge of actually understanding what third-wave feminism was doing, and instead reduce it to a catfight between fusty second-wavers and headstrong upstarts. The Morning After, Fire With Fire, and The New Victorians weren’t, for the most part, engaging with the flesh-and-blood young activists and thinkers who penned essays in foundational third-wave anthologies like Listen Up and To Be Real. They didn’t acknowledge the hip-hop feminism defined by Lisa Jones and Joan Morgan in Bulletproof Diva and When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost, or the transnational feminisms of Chandra Mohanty and Gayatri Spivak. It was more accurate to describe the trio of books, as Astrid Henry did in Not My Mother’s Sister: Generational Conflict and Third-Wave Feminism, as the work of women who simply “create[d] a monolithic, irrelevant, and misguided second wave against which to posit their own brand of feminism.”

This wasn’t just intergenerational slap fight: It was also a narrowing of the lens through which media and pop culture would consequently view complicated social realities and changes. In the case of The Morning After and date rape, hugely influential media outlets like the New York Times took what Roiphe herself had termed an “impressionistic” survey of elite campus life and served it up as fact. In making her a spokesperson for feminism, it used pushback against the book’s central failure of logic (date rape doesn’t exist, but if it happens it’s the fault of the victim) to buttress Roiphe’s caricature of whinging feminist indignation. And what Jennifer Gonnerman wrote in the 1994 Baffler article “The Selling of Katie Roiphe”— “Ultimately, Roiphe’s personal impressions defined the terms—and, more significantly, the limits—of the date rape debate”—has turned out to be all too true. More than 20 years later, there’s undoubtedly a far more sophisticated dialogue about campus sexual assault (for starters, we don’t call it “date rape” as much), and a wealth of writing, advocacy, and policy to address it. And yet there remain a substantial number of people with large media megaphones who blame rape on everything but rapists; and debates about how best to address and combat campus rape are still stymied by the belief that women are either outright liars or simply unreliable witnesses to their own experiences.

Excerpted from We Were Feminists Once: From Riot Grrrl to CoverGirl®, the Buying and Selling of a Political Movement by Andi Zeisler. Copyright © 2016. Available from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, a division of PBG Publishing, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.