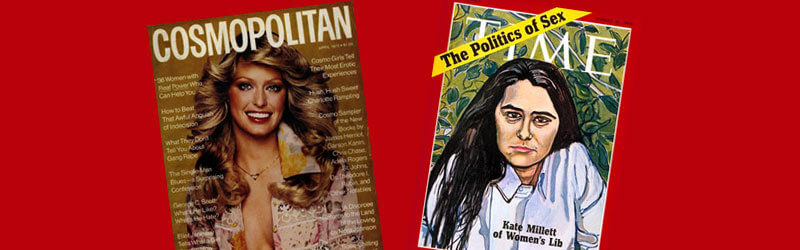

Helen Gurley Brown encouraged women to sleep their way to the top. Feminist Kate Millett warned that sex wasn't necessarily a weapon. Guess which message endured?

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

It was the fall of 1964, and petite and scrappy Helen Gurley Brown, the founding editor of Cosmopolitan magazine, was doing the rounds of talk shows to promote her book Sex and the Office. The book was a follow-up to her wildly successful Sex and the Single Girl, which had been published a few years earlier and catapulted Brown to fame and notoriety. By the time she walked onto The Mike Douglas Show in Cleveland, Ohio, Brown was a pro at the dishing out “between us girls” chit-chat, laced with the titillating innuendo that had catapulted her first book to such heights. That day, however, she walked into a trap. The audience of mostly housewives had been whipped into a self-righteous frenzy before she walked in, the task set before them, a taking down of the woman who thought sleeping with bosses (who inevitably had wives at home) was simply part and parcel of the professional woman’s arsenal.

Gurley Brown’s ambush-by-audience that September day had been set up by the show’s producer—a man named Roger Ailes. Ever the polite temptress, Gurley Brown did not take him to task when she returned to the green room. She presented no defense and no recrimination; there was no taking to task a man who had orchestrated her shredding by the crowd in the interest of producing talk-show theater. Taking men to task was not Gurley Brown’s style; after all, the book she was promoting was all about how the use of feminine sexual power could be deployed as a professional asset. Instead, Gurley Brown sent Ailes a note of appreciation for “putting her on the map in Cleveland.”

Ailes’s penchant for humiliating women in far worse ways has been just one of the grim revelations of an election season filled with tawdry and dispiriting expositions. For decades, many of them, like Gurley Brown, believed making it in a man’s world required putting up with sexual harassment and humiliation. Now speaking up, their accounts are harrowing, not least because Roger Ailes, who had to resign from his position at the head of the Fox News network because of them, is a dear friend and unofficial adviser to Donald Trump, the Republican nominee for president. Trump’s own position on “pussy grabbing” (“You can do anything”) has in the last few weeks of the presidential campaign, led to an even greater public discussion of the groping, harassment, and assaults that women continue to face.

The rise of predatory men, be they Ailes or Trump, may have contributed to an essential and crucial conversation among feminists about what men do and expect from women and the fraught and fragile position women continue to occupy even as one of them stands to become the next president of the United States. Within this outward-focused discussion, however, is an absence of how mainstreaming of one kind of feminism, the marketable, sex-positive Cosmopolitan brand peddled by Gurley Brown, may well have provided the arguments for women inhabiting the role of the office sex object. In the narrative of the Ailes-led Fox News, this meant being a pretty young thing that sat in the anchor’s chair, wore short dresses, endured gropes of powerful men until an expiration date came around and installed another woman in it.

There were, of course, other kinds of feminism. Gurley Brown’s book came out not long before Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, which the former eagerly reviewed for the column she had just launched. She agreed with Friedan’s arguments, she said, presented a flip and flaky synthesis of them and spelled Friedan’s name wrong the entire time. But Friedan’s book did not deal directly with sex, or the Gurley Brown (and then Cosmopolitan) prescription that women should embrace their role as sex objects (chapter six was titled “How to Be Sexy”) and hunt, catch and land men. Like the magazine that would carry on the book’s chatty how-to-be-better-at-sex prescriptive, there was a small dose of revolution within it, the freeing proclamation that women could (and should) enjoy sex outside of marriage. This, Gurley Brown’s single act of moral rebellion, earned her deafening applause and a vehicle (Cosmopolitan) through which it could be marketed into the future. With a marketing prescription attached to it, sex-positive feminism, where women uncritically embraced sex and set about to figure out each and every possible way to be sexy, was set to conquer and dominate all other sorts of feminisms.

It didn’t have to be so. In 1969, seven years after Sex and the Single Girl was released, a young woman from Minnesota penned a dissertation that would be published under the title Sexual Politics. Unlike the chirpy, eager-to-please Gurley Brown, Kate Millett cast a skeptical eye at the sex act itself, arguing that sexual relations were themselves imbued by the inequalities of patriarchy. The first chapter of Sexual Politics (which was reissued this year) quotes passages from D.H. Lawrence, Normal Mailer, and Henry Miller. Demeaning and degrading in their descriptions of women and their body parts, the passages and works are nevertheless considered explications of the authors’ literary genius. In deconstructing them, Millett revealed not simply that sexist depictions of women are permissible but that they receive great admiration and adulation as expressions of art. In later chapters, Millet presented the works of authors like Jean Genet, which are not concerned with the establishment of male dominance of women.

Sexual Politics was embraced when it was released, both by the feminist movement and general public. It sold over 15,000 copies and went into a fourth printing, an estimable effort by a book that was considered feminist literary criticism. On August 31, 1970, TIME magazine featured her on their cover with the words “Kate Millet of Women’s Lib.” For a few years, Millet’s thesis remained a crucial part of the public debate: Women should embrace their sexuality but recognize the sex act and the construction of women as a sex object as a product of patriarchy, meant to demean and render inferior. If Gurley Brown’s feminism was fun and flirty, egging women on to have affairs and not feel remorse for it, Millett exposed the sexism within sex, its potential to keep women imprisoned in constricted roles that, for all their apparent moral radicalism, were just another way of having women service men.

Sexual Politics and its cautionary thesis could not endure. Millett, writing in 2001 (Mother Millet), described its gradual fading: “There was much noise with Sexual Politics in 1970 and for a few years after and then, a silence.” The silence lasted a long time; while Millett continued to write, authoring several books and essay collections, Sexual Politics itself even went out of print, not reprinted until this year when its launch garnered some small attentions. Unlike Gurley Brown, who by the end of her life in 2012 had amassed a large fortune, the author of Sexual Politics was, in 2001, worried about being able to cobble together the $12,000 from checks and royalties that she needed to sustain her.

The uncomplicated sex-positive feminism of Sex and the Single Girl has endured because of its early wedding with a consumer market that danced at the opportunity of selling to women, With being a sex object now constructed as an act of feminist choice, a whole array of products could be sold to women engaged in the quest of becoming sexier, lipstick and lingerie, sex toys and shape wear. The pages of Cosmopolitan burst with advertising and the ad revenues bolstered the position of the fun and flirty feminists who were choosing to be sexy.

And so it was that sex-positive feminism won the day. Helen Gurley Brown’s acquisitive definition of success, her diamonds and her millions, was compatible with the capitalist society in which she sold it. Women were in the workplace and there to stay; that Gurley Brown’s permission for single girls to have sex equaled workplaces where men expected single girls to have sex, was not an objection that gave anyone much pause. Nor was any serious thought given to the idea that while women should be free to choose to have sex, existing arrangements of power and patriarchy made them less powerful within the act itself, more likely to domination and humiliation, to be abused at the hands of men who continued to wield power, benefit from a male defined status quo.

It is the fallout from this uncritical embrace of sex-positive feminism that undergirds the silent and dark realities of what women continue to face today. In books and magazines and products, the market agenda of sex positive feminism leaves little room for a critique of existing structures. With everything defined in the language of choice, there is little time or effort allotted to considering how the nature of choices themselves are not equal, and that a woman who “chooses” to sleep with herni boss is less free to decide or deny than he may be. Young women enter college campuses and then workplaces schooled in the cool sex-positive feminism that has been adopted by popular culture but without the safe spaces and resources to discuss and report campus rapes and assaults.

Helen Gurley Brown died in 2012, but the magazine she left behind continues to peddle her prescriptions. Cosmopolitan’s November cover features actress Zooey Deschanel, against whose face are the words “Hot Moves No Man Can Resist: Caution Extreme Pleasure Ahead.” Pleasure and pandering are thus mixed up, serving up a dish in which women will not be able to tell them apart, where pandering to “Him” is pleasure. On the other side of the fence, Kate Millett, who was recently inducted in the National Women’s Hall of Fame, is remembered only in Women’s Studies courses, the sort of required reading that seems clunky and irrelevant to new generations raised under the supremacy of sex-positive feminism. They know that saying “no” is their right, but cannot dissect the complexities that lie behind saying “yes.”