Nearly half the people killed at the hands of cops have a disability, including Alfred Olango and Deborah Danner. Imagine the statistics under a president who openly mocks the disabled.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

In late October, a 66-year-old Bronx woman named Deborah Danner was in the grips of a schizophrenic episode and needed to be hospitalized. A neighbor called 911 to report she was behaving erratically. The NYPD showed up—and shot her to death. This starkly illuminates a fear faced by I think most all parents of children with mental illness or other cognitive disabilities.

And why I haven’t wanted my son, J, to grow up. Literally.

On the outside, J is a handsome, even angelic-looking 16-year-old. But he has autism and other developmental delays that can make understanding the world—and vice versa—difficult. Although it was a lifetime ago, people still remember what a delightful, precocious baby he was. But two major emergency surgeries for spinal cord tumors when he was 18 months old left us somehow coincidentally with a severely cognitively disabled child with ongoing medical issues—and autism.

This might be why in my mind, he’s still a toddler, that toddler who loved to “read” books with me, the one who astounded friends by saying “thank you” to them when he was barely out of infancy. One of our last normal moments was on vacation on Cape Cod with extended family. J was trying to push a toy lawn mower, but he kept falling. That was our first hint that anything was wrong. That, and the way he looked at me, as if to say, “What’s happening? Why aren’t my legs working?”

It’s for this boy in my memory that I still haunt the children’s section of stores, futilely hoping to extend his childhood just a few more months by buying the “husky” XXL jeans in the children’s department, and not the men’s. Perhaps partly due to his condition, his voice is still sweet and reedy, despite the fact that he’s turning 17 in January. But, his face is thinning, he is growing muscles. His becoming an adult means no more automatic allowances and compassion we often give children. As he gets older, it also makes me more aware that my husband and I won’t be around to protect him forever. I am haunted not by the past, but by the future.

When J turned 16, my husband and I joked that J should start driving us around. The joke in some ways exists only because in the last couple years, J’s made enough progress that instead kicking the car windows or disturbing the driver as he used to, now we actually can take car trips with him. We put up with the expense of keeping a car in the city because J enjoys car rides—most of the time—and it is one of the primary ways we can go on vacation as a family.

But he may never drive, even though he is old enough to do so. He’s also reached an age where a meltdown in public that leads to him hitting me or one of his young female aides no longer appears to others as autism—people see him committing criminal assault.

In her six-page essay “Living with Schizophrenia,” Deborah Danner described the nightmare of being an intelligent, lucid person who finds herself dangerously out of control during her crises. Citing a 1984 case of Eleanor Bumpurs—another black woman in her 60s who was shot to death by police in New York while in the throes of a mental health episode—Danner described the woman’s senseless death hanging over her life like a Sword of Damocles.

Danner wrote the essay four years ago. She went on to stress the necessity of training the police to deal with people in neurological and mental health crises. Perhaps, had that been done, she might be alive today. So might, for example, Alfred Olango, a mentally disturbed man who was walking in traffic. His sister called 911 for help, making sure to identify him as mentally ill, and the police who arrived fatally shot him. There seems no clearer example of the criminalization of cognitive issues, often compounded by race, than this summer’s attempted shooting of an adult autistic Latino patient man who was sitting in the street playing with a toy truck—the bullet missed him and hit his black therapist who had been clearly and loudly identifying his client’s disability to the police the entire time.

People with mental illness and cognitive disabilities, the signs of which are not always readily visually apparent, are legion. The Center for Disease Control estimates one in 68 schoolchildren currently have autism, a building tsunami of adults who don’t understand social cues, have barriers to communication, and can be violent. But as Dr. Jeremy Kidd, chief resident in psychiatry of Columbia University Medical Center points out, “While popular culture and political discourse often link mental illness with the perpetuation of violence, the reality is that people with mental illness are more likely to be victims of violent crime.” A 15-year-old African-American autistic boy running a cross-country meet in Rochester became lost on the course and was assaulted by a white man, who took the trouble to leave his car, approach him and attack him, because, he claimed, he was scared of the teen. Egregiously, a judge agreed and did not allow the autistic teen’s mother to press charges (they are, however, reopening the case after the outcry over this decision). But it’s clear how the law criminalizes disabilities even in this situation where the autistic teen was clearly the victim.

One way our son reacts to overwhelming stimuli is by blindly lashing out, as he did on Halloween when a man in a costume leapt out from a doorway and tried to scare him as he walked home from school with an aide.

A few years ago, when J was still small, he had a meltdown in a supermarket and bit me. My husband and I managed to get him back to our car, where he could reorganize himself safely. In the meantime, someone had called the police (to this day, I’m not sure why, but perhaps they thought we were kidnapping him assuming why else would he bite and scream like that). The officer who appeared on the scene miraculously correctly sized up the situation (the lady who called 911 hastily drove off before I could question her). He didn’t demand we step away from the car, he didn’t get into J’s face. He spoke with us quietly, left J alone, as if knowing any intervention would have just escalated an already fraught situation.

It turned out the man had a nephew with autism. He didn’t even give us a citation, he just continued on with his day, and we did, too—shaken but grateful. Perhaps with more training, more exposure, more familiarity, police can similarly learn how to assess and handle these kinds of situations. If my son might harm someone, I would want officers to intervene to protect bystanders or his aide or me while also holding open the space to realize that, with his disabilities, J literally cannot have criminal intent.

In her essay, Danner eloquently wrote about her long nightmare of mental illness, living with its unpredictability, the loss of control, how it didn’t reflect the intelligent person she was. She often lamented about the stigma of mental illness, how those who do not suffer from it believe “the worst of those of us who do.” She was, like us parents who know we won’t be physically here for our children eventually, haunted by the future. She needed help, not harm. After three decades of suffering through what she called her “curse,” her life ended tragically in the way she most feared. She was also, like Eleanor Bumpurs before her, a person of color—part of not one but two groups particularly vulnerable to mistreatment and misunderstanding by police.

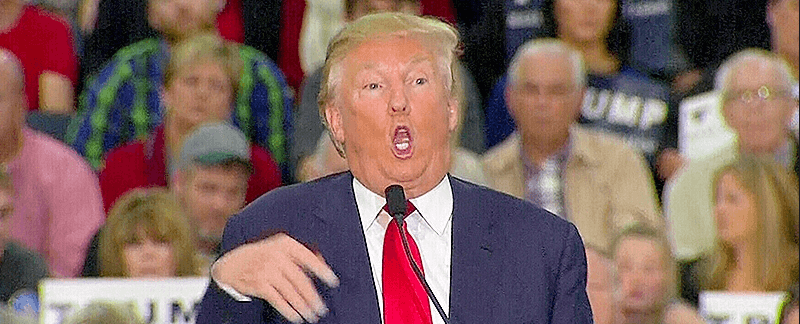

And for New Yorkers, the nightmarish quality of this presidential election includes the sudden reemergence of the sinister former mayor Rudy Giuliani as a sidekick to and henchman for the newly elected Donald Trump who famously mocked New York Times investigative reporter Serge F. Kovaleski. During Giuliani’s “law and order” tenure, there were a number of notorious police brutality cases, among them the fatal shooting of Amadou Diallo, an innocent man shot 41 times. Giuliani has doubled down on his “shoot first, ask questions later” rhetoric, telling MSNBC, “When a police officer tells you something, do what he says.” But what about people like my son, who can’t understand a cop’s instructions?

As a parent ever alert to changes that may affect my son, the election results adds another fold in the complex and fragile origami that holds our son’s life together. Can we count on the Americans with Disabilities Act as any kind of protection in a looming “law and order” Trumpian world?

This morning my son wanted me to chase him before he went to school. In our game, I “catch” him and tickle him, now profoundly grateful that he surfaces out of his autistic world to beckon me in, giving me a half-remembered glimpse of that happy pre-surgery 18-month-old. But when we stand up and measure ourselves back-to-back (exactly the same height, today), I realize I am also proud of the man he is becoming.

As we move on in such a climate of uncertainty, all I know for sure is that Deborah Danner should be alive today, but she is not. My son, who doctors once thought would be dead by 2, is alive and I will always protect him. But life is not infinite and we must all work for a world safe for people like Deborah and for J. Ill people don’t deserve a violent death at the hands of police. Let us not let her death be in vain.