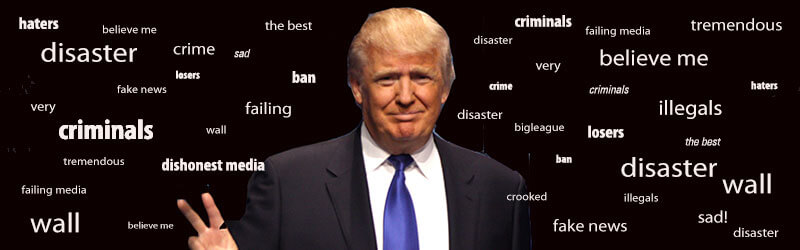

Like elections, language has consequences. And Trump’s “best words” are as terrifying as his executive orders.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Three weeks into the Trump administration, and it’s no exaggeration to say that we find ourselves confronting a new world order. There’s the constantly lengthening list of rights that have already been restricted or are under threat, nearly all of them informed by a racist, sexist, isolationist, and punitive worldview. There’s our loose cannon Commander in Chief, flapping his gums—and his Twitter fingers—indiscriminately when talking to or about world leaders, putting both strong and fragile relationships in peril, as well as (inter)national security. There’s the alarming frequency with which the administration lies (and the more alarming fact that they are utterly unrepentant about this), and the ever-expanding registry of conflicts of interest: the increase in the Mar-a-Lago membership fee and the fact that the sum still isn’t high enough to keep out an immature braggart who posts pictures of the nuclear “football” on Facebook; the failure to fully transition Trump’s business interests into a blind trust; at least one violation of the “no new foreign deals” promise he made while campaigning; a Cabinet chockablock with secretaries who haven’t divested themselves of businesses that overlap with their new positions; a counselor who brazenly promoted the president’s daughter’s fashion line during a press conference, saying “I’m going to give a free commercial here”; and a flagrant disregard for long-held standards and policies, expressed most chillingly in Trump’s executive order that gave white supremacist Steve Bannon a seat on the National Security Council.

That’s a lot to cause worry—and it’s hardly an exhaustive list. Just as troubling, however, is the speed with which these assaults and slights are registering and reflecting themselves in the language we’re hearing, reading, and speaking. We find ourselves trying to understand what it means to go from a president who is an avowed bibliophile and accomplished scholar–writer himself, to one who seems rather proud that he doesn’t read regularly (he’s too busy, he says), who frequently uses words incorrectly, whose inauguration portrait contained a typo, and whose books were penned by a ghostwriter who has admitted, in his own words, that his work was “put[ting] lipstick on a pig,” a lucrative but not so illustrious gig he now regrets. We have Kellyanne Conway trying to convince us that lies are “alternative facts” and a Department of Education headed by a billionaire who can’t seem to find someone to run the DoE’s Twitter account without tweeting an egregious typo (spelling “W.E.B. Du Bois” as “W.E.B. DeBois”) followed by an apology containing yet another typo—in the word “apologies,” no less.

For those of us who love words and make our living with them, the casual yet sinister manner in which Trump and his cadre handle language is as terrifying as his executive orders. But make no mistake, says Ebonye Gussine Wilkins, a social-justice writer and editor who specializes in inclusive editorial standards; the administration’s seeming linguistic clumsiness is, she says, “an unsettling combination of careless language usage and calculating language framing.” Our job as citizens and witnesses is to be on high alert when it comes to the administration’s messaging. “As we hear these terms and framing over and over,” she warns, “we begin to internalize them and keep them in motion. While it is very important to unpack the language being used in order to counteract it, we must not mistake what is being said for clever, carefully crafted responses—they are not. What this language usage is doing is altering our perception of reality and laying the groundwork for more of the same.”

As a writer and journalist, I’ve been taking Gussine Wilkins’s wisdom to heart. We’re less than 30 days into this administration (I KNOW), and already, we’re all exhausted, writers and journalists included. But there are certain categories of folks—lawyers, activists, and, yes, journalists among them—who simply can’t capitulate to fatigue. We have a particular responsibility to remain vigilant. For journalists, that means staying watchful, not only to Trump & Co.’s language, but to our own and to that of our colleagues. This means having challenging conversations about our professional ethics and personal moral values, and talking about how these two intersect. For some media outlets, it means profound policy-oriented growing pains, as has been the case at both The New York Times, which has embraced the use of the word “lie” to talk about, well, lies, and NPR, where the same word in the current political context remains verboten for now, and where at least one reporter has actually been fired for “exploring what it means to do truthful, ethical journalism with a moral compass in this very complex time.” And finally, this watchfulness also encompasses the work of educating readers—especially people in our immediate circles—about how to consume media in a more critical, thoughtful way.

I started thinking more about all this late last week, as rumors about Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raids were substantiated and reported by news outlets. A February 10 article in The Wall Street Journal did a solid job of summarizing the scope of the raids, but included this innocuous sounding sentence: “The agency said 160 foreigners were arrested in six Los Angeles-area counties this week, and said about 150 of them had criminal histories.”

Criminal histories.

It was a phrase whose coding was easy to miss. After all, we’ve been hearing it for so long, and always without nuance or further explanation. We knew as early as November 2016 that Donald Trump would pursue the deportation of immigrants with “criminal histories.” He said it more than once, but most pointedly during an interview with “60 Minutes”: “What we are going to do is get the people that are criminal and have criminal records, gang members, drug dealers, where a lot of these people, probably 2 million, it could be even 3 million, we are getting them out of our country or we are going to incarcerate [them] …”

It was a sound bite that played perfectly to Trump’s base, white folks who are terrified of immigrants with criminal histories or “criminal records” (though, curiously, never seem to be as terrified of homegrown, white, U.S.-born gun-wielders who, like Dylann Roof, have perpetrated heinous violence on American soil under a banner of white supremacy).

Unfortunately, what many of them failed to understand or acknowledge—and what many people who didn’t vote for or support Trump probably missed, too—is that “criminal histories” and “criminal records” are interchangeable phrases that are all but meaningless. “Criminal” sounds scary and appealing at the same time: Who wouldn’t want to root out the criminals in our midst? And yet, “criminal record” or “criminal histories” can mean almost anything, and standing outside with an open container of beer, for instance, isn’t the same order of magnitude as, say, raping or killing someone. Yet being charged for having an open container—and a host of other “quality of life” infractions, including littering, public urination, and tagging a building with graffiti—can all set the wheels of the criminal justice system grinding into motion, and can result in a criminal record in the process. A rap sheet can easily grow longer if, say, you don’t keep a court date because your car broke down on the way to the courthouse or your childcare fell through at the last minute. Now, you’ve “failed to appear” and a bench warrant can be issued for your arrest. You are officially a criminal. From here on out, it won’t get easier and is likely to get harder. You might lose your job because there’s no boss understanding enough to give you the days off that you’ll need for your remaining court appearances. You might lose your kids because your court appearance keeps you from picking your kids up at school, and the school might call Children’s Services, whose caseworker is now questioning your ability to parent. The vortex of criminality can suck you in and pull you down quickly.

If you’re fortunate enough to have never had contact with the criminal justice system, then you probably don’t know this, and so the use of “criminal record” or “criminal histories” does exactly what Trump hopes it will do: scare you. Better still if it scares you to the point that you take up his anti-immigrant banner, adding your voice to the “Boot them out and build a wall” chorus. And best of all if that fear beats you into social and mental submission, if it makes you so afraid of others that you’re not willing to hear their stories and if you refuse to even try to understand the structural, systemic problems that push people with minor criminal offenses ever deeper into the “justice” system, a system in which, no doubt, you have invested your complete trust.

But this shorthand of “criminal histories”, and many examples like it, obscures ideas and ideologies, dogma and dynamics, that are important to pay attention to, now more than ever. The imprecision of language, our careless use of words and phrases that are so familiar that we’re not even sure we know what they mean anymore (if we ever did), has consequences. “Our words are not without meaning,” as Black feminist scholar bell hooks reminds us. We know this … and yet, the temptation is to stop paying attention. Constant vigilance is wearying. Stay awake. By failing to write and read critically, to think hard about meanings, we fail to keep ourselves and others accountable for holding words up to the light to see if they are correct and true. We hand Trump the primer he needs to establish the new reality and new perceptions about which Guissine Wilkins warns us.

And that’s not a reality in which we want to live.