From a very young age, girls are taught that being skinny is a virtue and consuming “too much” is sinful. Will women ever be able to eat and drink without guilt?

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

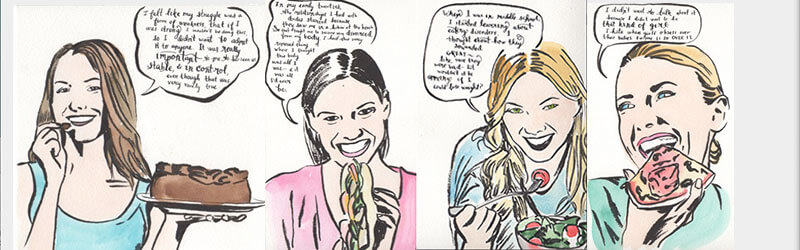

The images in this essay are drawings based on search results from Google. The words are from anonymous women I spoke to about eating.

The studio where I draw in Chicago is attached to lots of other artist’s studios, separated by thin walls and thick canvas curtains. This is wonderful if you, like I, enjoy eavesdropping. I have heard people talk openly about sex, other people they dislike, their own worst habits, and nasty little secrets. Recently, I overheard two girls a few studios down talking candidly about food.

One girl said, “Ugh, I have been working on this project for two days straight and I haven’t had anything but coffee since before I started. I think maybe I have an eating disorder?”

The other girl laughed and said, “Yeah, but all girls have an eating disorder.” That made the first girl laugh, and then the conversation moved on.

I, on the other hand, did not move on. All girls have an eating disorder. Was that true? I mean, obviously not every girl on the planet has an eating disorder, but when I thought about it, it was remarkable that every girl I could think of had at least a very complicated relationship with food. Why didn’t we name our relationships “eating disorders”? Maybe we all did, privately, without telling our friends or our doctors; maybe we were all silently suffering, thinking that we shouldn’t talk about our eating disorders because they weren’t important enough to talk about.

I went home and posted an open call to my Facebook wall: “Do you feel like at a point in your life you had what could probably be called an eating disorder, but you were never officially diagnosed with one?” I asked self-identified women to message me if they felt comfortable talking about it. When I posted the call I thought, I would never respond to something like this. I would never be willing to talk on this subject. I figured maybe I’d get one or two messages, if that. By the next day, I had heard from 113 women. I got so many messages I had to remove the post so I wouldn’t feel overwhelmed.

I heard from all kinds of women whose relationships with food were diverse but troubled. There were women who had been binge eating since they could remember, and had never dared to talk about it; there were women who still starved themselves for weeks at a time because it gave them a sense of control; there were women who had stopped purging but occasionally wished they still did it because it was nice to eat so much food and not gain any weight. Ultimately, I had conversations with 20 women, ages 21 to 50, of different races, and of different shapes and sizes. Mostly, I was struck by two things. First, almost unanimously, the women thought about food in relationship to their body daily—even if they no longer considered themselves “disordered.” And second, everyone felt a little freaked out to talk about this subject: I heard a lot of variations on, “I have only just now started to realize what a problem this has been,” or, “This is very triggering for me,” or, “I haven’t really told anyone this.”

When you do a Google image search for “woman eating,” you get a very distinct picture of the way we are supposed to think about women and food. Women who eat, apparently, are white (that’s a problem stock images have in general), have shiny hair, are supermodel-thin, and are very happy about eating. You can find this kind of woman eating anything: She is happy and skinny while eating crisp salads with cherry tomatoes; she is happy and skinny while eating foldable New York-style pepperoni pizza; she is happy and skinny while eating multi-patty burgers that couldn’t possibly fit in her mouth.

In pop culture, the same idea is ubiquitous: The Gilmore Girls are happy and skinny while going on regular pizza-Chinese food-Twinkie-chocolate binges totaling well over 10,000 calories; the 2 Broke Girls are happy and skinny while they eat cake fries and comment joyfully on their willingness to eat anything; Charlotte McKinney is happy and skinny while she bites into a massive burger from Carl’s Jr. Women must be seen as people who simultaneously don’t diet and don’t gain weight, and who stay perfectly blissful throughout.

In talking to women about their relationships with food, I thought of the Google image search over and over again. Food makes women anything but happy. I mean, maybe it makes us happy for a while—Oreos are like cocaine, after all—but ultimately we spiral into familiar patterns of shame: We rely on food to deal with anxiety, then experience guilt for eating so much, and then eat more to deal with the guilt. I wondered what it would look like if the Google-image-search women might say what some of the women I talked to said.

My own fraught relationship with food began to develop when I was 8, and they’ve persisted since. At 7 I still looked like a kid who played outside: I was gangly with rubbed-out knees. I did not like to play outside, though; my metabolism just hadn’t caught up with my habits. (I spent all my free time drawing pictures while eating handfuls of jellybeans; during recess, I read “Babysitter’s Club” books under the play structure, hence the misleading knees.)

When I turned 8, I got my hair cut into a bob at a bargain stylist. She said, “Oh, this is a great cut for you! You’ve got such a pudgy little face; now we can really see it!” And that was true: At school, the skinny girl whose haircut I’d copied saw me and said, “Why did you cut your hair? Now you look fat.” Now I looked fat, and so began the rest of my life.

I have kept a daily diary for the past 20 years or so, which is a unique artifact for anyone who grew up in the burgeoning digital age. My daily diary, however, is really little more than physical proof of a broken connection with food. Day after day, year after year, entries contain lines like these: “I am so fat and I don’t know what to do about it”; “Today I didn’t eat anything at all, and my stomach is making crazy sounds, but I feel so good in a way”; “Yesterday I ordered a pizza from my bed and ate the entire pizza, even though I am supposed to be vegan. I wanted to throw it up but I don’t know how other girls do that; I couldn’t throw it up even though I really tried.” There’s a record of the week in seventh grade when I drank only diet soda and chewed gum, and of my grandmother pulling me aside to tell me she wanted me to join Weight Watchers when I was 13; and of the four months at the beginning of high school when I went vegan and started running and lost 100 pounds. I want to say that I spent time in my daily diaries writing about other things with equal enthusiasm. Girls are supposed to write about their crushes and their frenemies when they’re young; existentialism and monogamy when they’re older. I did not write about those things with much frequency at all. I wrote—and continue to write—about food.

I never really thought about any of this as disordered eating. I probably would have given it that label had I been more honest about it when I was in regular therapy, but I was always bad at therapy. I treat all early exchanges in relationships like job interviews, and I didn’t understand why a closed door and a confidentiality agreement should make that any different. I colored my conversations with my many therapists in the sunniest possible hues, sometimes implying that I got sad or had highs and lows, but I never brought up food; none of my therapists ever asked, because after all, my body looks (as it has been described to me by various people in my life) “really normal.”

“Normal” is a funny word to use for a body. If we are to draw any conclusions from recent (if aggressive) Dove soap campaigns, all bodies are different, and that’s what makes them “beautiful.” All women are walking around with singular, unparalleled bodies, and we are all supposed to love ourselves exactly as we are. At the same time, we are supposed to know that our bodies aren’t good enough exactly as they are, and that while we are loving our bodies, we should also be actively trying to change our bodies. We should not be trying to get “skinny,” we should be trying to get “healthy,” which is synonymous with “skinny,” but never calls itself that. While we might understand that statistically our asymmetrical curves and various idiosyncrasies are “normal,” we should also understand that enough women look like the women on the covers of magazines for those women to fill the pages of magazines, too; and so it is not impossible to look like such women. You should not want to look like one of those women, but if you end up looking like one, you will be rewarded by being photographed for a magazine.

Above all, none of this should be talked about. You are expected to know about it but not talk about it. Only women with “successful” eating disorders are allowed to talk about them: That is, you can talk about it if your eating disorder is really, really dangerous. Otherwise, let’s not talk about food or our damaged relationships with it. I am not trying to downplay the dire importance of awareness around hospitalization-level eating disorders (they’re actually very common); I’m merely suggesting that there is a whole category of private, food-obsessed women who never talk about their eating habits, and maybe ought to.

I saw a book called Things No One Will Tell Fat Girls: A Handbook for Unapologetic Living by popular body-love blogger Jes Baker at a bookstore that immediately piqued my interest. But I didn’t want to anyone to see me pick it up (because that might make people think I was fat; or, worse, that I cared about people thinking I was fat), let alone buy it, so I surreptitiously brought a copy to the back of the store and read the whole thing in one sitting. Its central tenet—as supported by corroborative statistics and several excellent essays by guest writers—is that it would do us all a lot of good to love our bodies just the way they are and that such a task is extremely difficult. She writes, “We are taught that our outsides are flawed, and not only that, but the majority of our worth lies in our physical appearance, which, of course, is never ‘good enough’ according to our society.”

My impression is that if I were a “good” woman or a “good” activist, I wouldn’t think about my body much at all. Thinking about my body all the time is narcissistic; people who are doing the really important work in this world are not dieting or weighing themselves—they’re volunteering with civil-rights organizations and doing research on sexual violence. I want to be one of those people. The world is suffering, and the more time I spend obsessing over superficial ideas about beauty, the less I have time to help. And yet: I think about my body all the time. I think about it when I’m having sex; I think about it when I haven’t had sex in a long time; I think about it when I buy clothes; or when I try on clothes I haven’t worn in a while; I think about it when I see my thin friends; or when I see my friends who have put on some weight; I think about it when people around me say they prefer “fit” women; I think about it when I’m watching television. And since I know it is wrong to be thinking about it, I don’t talk about it. I just feel guilty for thinking about it. I add my thinking about it to the list of all the things that are wrong with me.

Disordered eating is considered a mental health condition, which makes sense since our modern relationship with food doesn’t seem far from relationships with other darker, more lurid substances that are used for emotional departure: Vodka, marijuana, heroin, tequila—those intoxicating tools which sound so grown-up. I eat to quell my anxiety, and so I eat all the time. Foods that come in bags are particularly thrilling: the metallic unsealing, the stale smell that wafts up from inside, the way those foods usually crunch in tempo along the back teeth. This lets me leave: The rhythm and dopamine distract from whatever is bothering me. In eating, I do not have to be present with my pain.

One in five Americans now suffer from some sort of mental-health issue—at least, that’s the number that’s reported. Given the stigma that surrounds psychological disorder, I would not be surprised if that number was higher. This is not to imply that everyone who has trouble with mental health also has trouble with food or body image. And yet, all people do eat food, and all people do have bodies; many mental health problems stem from a variation on self-loathing, and food is such an easily available mood stabilizer. I wonder how much we are not talking about some of our food issues because there is a sense of societal fear.

According to the National Association of Anorexia and Associated Disorders, 91 percent of women have attempted to control their weight through dieting. So regardless of whether we should care about the way our bodies look to the outside world, most of us do. And yet, is unpopular to talk about any of this: No one wants a woman to talk about the diet she is on or how much weight she’s gained or lost. A recent study suggests that women who talk negatively about their weight—regardless of what their weight is—are less likable than women who don’t. The New Republic reported that “talking about nutrition—or appearing weight-conscious at all—has become taboo for women, while men feel more and more liberated to embrace and advertise food-related anxieties.” This doesn’t mean the anxieties have gone away; it merely suggests that women aren’t allowed to talk about it anymore. The obsessive thinking that blossoms around eating habits must be tampered. It’s important that girls stay happy and skinny while nonchalantly eating everything they want.

I am writing this selfishly. I want to feel less alone. For all the time I spend trapped in my own body, feeling hopelessly attached to but never in possession of, I wonder if there are countless others who feel the same. My memories are marked with human error: In middle school, kids threw popcorn at me and made oinking noises; I dated a boy who told me my body looked swollen like a drowned corpse; I dated a girl who told me that my weight distribution was unusual and that it was hard to look at me naked. There have been plenty of others who have said nice things—“I love your breasts,” “You look like a goddess,” “You move like a tree”—but those are not the things I replay repeatedly. I believe I am not alone in this. I can’t count the times I’ve heard a girl bemoan how other people tell her how pretty her face is. It is not coincidental that we cling to the shortsightedness of others.

Yes, this obsession with physical beauty is antiquated if not detrimental. Yes, it is time we rose above these surface-level definitions of worth and meaning. Perhaps the first step is an acknowledgment. We are all screwed up; no one is happy all the time about the way they look; we’re all selfishly wishing something about us would change; and while that’s not ideal, it’s okay. Until we build a different world in which all body types are represented and food is talked about openly and in earnest, at least for now, we have each other.