Number 45's speech at the national jamboree, where he dissed Hillary Clinton and President Obama, wasn't just offensive, it was downright dangerous to the future of this nation.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

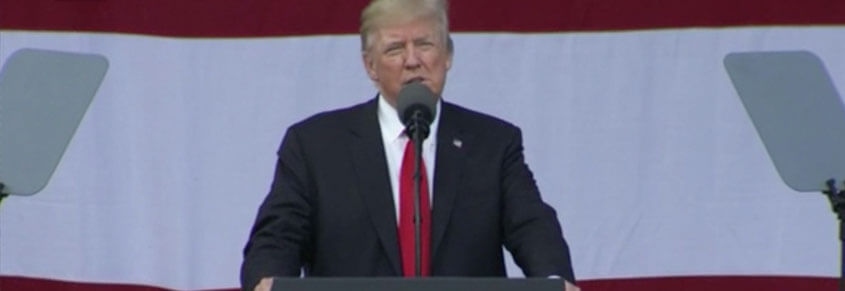

In a disjointed, rambling, semi-coherent speech before the Boy Scout National Jamboree in West Virginia yesterday, Donald Trump once again proved himself to be incapable of following the minimum standards of acceptable behavior. Comparing his talk—in which he rehashed his electoral victory, bragged about the size of his inauguration crowds, trashed both President Obama and Hillary Clinton, and talked about a party attended by “the hottest people in New York”—with those given by other presidents is illustrative. As the Washington Post pointed out, “Franklin Delano Roosevelt used the occasion to talk about good citizenship. Harry S. Truman extolled fellowship: ‘When you work and live together, and exchange ideas around the campfire, you get to know what the other fellow is like,’ he said. President Dwight D. Eisenhower invoked the ‘bonds of common purpose and common ideals.’ And President George H.W. Bush spoke of ‘serving others.’”

We’ve seen Trump do this kind of thing before, turn a celebratory or solemn event into essentially a campaign rally for himself. Previous inappropriate remarks took place at the CIA headquarters, his first address as president, and just last week at the commissioning ceremony for the Navy’s newest vessel, the USS Gerald Ford, at which he demanded that service members call their senators and push for a repeal of the Affordable Care Act.

So why is what he did yesterday to the Boy Scouts so uniquely offensive? After all, the Boy Scouts is an organization that has its own unsavory history. The persistent homophobia, historic links to conservative religions organizations (though many have recently cut ties because the Scouts have gotten better on issues of diversity), and casual racism experienced by many Black scouts at group gatherings like this have long been noted. There are lots of parents—like myself—who feel torn about wanting to send our sons into the organization. For all the obvious benefits in self-esteem, learning to work as a team, and gaining skills in and out of the woods, there’s a persistent shadow over just what other lessons boys in the Scouts learn.

Still, there’s something particularly beyond the pale in the way Trump used their annual gathering as an echo chamber, or really an applause machine. He whipped them up into a frenzy, left them chanting his name. It’s disgusting that he did this because these are, after all, children. And children, for all their intelligence and good sense and innate curiosity, can be easily manipulated—especially when they’re in a crowd.

Even the boys whose parents would never support Trump or sanction his giving a speech of this kind must have joined in. Joining in is a particularly useful tool in childhood and adolescence—standing apart from the crowd is never more difficult (which is probably why we are so impressed, justly, when a young person makes an independent stand). Those who study the psychology of crowds warn that being in a large group tends to reinforce poorer decision-making, not better.

Kids can see situations more clearly than adults sometimes. Because of their inherent power deficits, they can be great judges of character. Babies loved Obama, and from what we can tell in photos, they do not feel the same way about the current president. But children are also easily manipulated by the adults in their lives—the people they trust—and by the mood of their peers. A crowd of children cynically used to lend their wholesome energy to an authoritarian leader, well, it smacks of North Korea, or Nazi Germany.

It’s easy to anticipate the “both sides do it” critique here. After all, children have always played a role in politics: whether as props, pawns, symbols, or voices of conscience. There were the young marchers in Birmingham in 1963, demanding civil rights, mountains of courage in their small bodies. There was Samantha Smith, the Cold War peace activist who went to the Soviet Union in 1983 to bridge the gap between nuclear superpowers with nothing but her good will. There is, now, Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani teenager who survived being shot in the head for her work advocating for girls’ education. But these children were undertaking political action for things that really affect them. While their parents and other adults may have guided them, their advocacy was for their own future.

What Trump did in that Boy Scout Jamboree was different. He wasn’t talking to the boys about their future—except in those brief moments when he hewed to the prepared script, which was itself pretty bizarre (why would he choose William Leavitt, whose suburban housing developments were segregated, as a role model?). Mostly, he used them as a captive audience to reflect his own grandiose self-image. He wanted them to laugh and applaud when he mocked his political opponents, to shout encouragement when he told them about his election victory, to cheer his promise to bring back “Merry Christmas,” a phrase that honestly has never gone anywhere.

What saddens and angers me the most about Trump’s misuse of this platform is less that he’ll turn those kids into alt-right monsters, or even fervent Republicans. It’s that he’ll disillusion them from caring about anything at all. That he’ll turn them into the kind of people who think politics is a gladiator sport, or a reality television show, rather than an arena in which we (the people!) come together and decide how we want to help one another.

As a very young girl, I had a serious lisp and couldn’t say any Rs. My father, a college professor, had graduate students who loved to hear me say the name of the Democratic nominee for president in 1968, when I was three: Hubert Horatio Humphrey. They would make me recite it and laugh their heads off. (Similarly, I used to crack up when my son, at around 2, called Barack Obama “Bronco Bomma.”)

I cringe a little now—Humphrey wasn’t their top choice for nominee (they would have supported Eugene McCarthy or Robert F. Kennedy), but he could have saved the country from what came next: Richard Nixon. I was 7 when Nixon was re-elected in 1972, and watched the Watergate scandal unfold just as my own understanding of adult fallibility did. Nixon lied and cheated, my own parents went through a vicious divorce, I got in trouble at school for calling for the president to be impeached. Grownups, I learned, weren’t all they presented themselves as being; They were just as weak, scared, and angry as I was.

But by 1976, during that Bicentennial summer, I felt patriotic. I was reading Johnny Tremain, imagining myself as a brave young kid running messages for the Sons of Liberty. I believed in the country that had sprung from ardent debates about independence and the rule of law. I knew the adults in charge hadn’t always done a good job, but there were good ideas there, worth fighting for. (I was a year or so away from understanding the bad ideas also baked into our country’s founding, and how thoroughly we still suffer from that original sin.) In other words, I was figuring out, by the age of the average Boy Scout Webelo, that I could love the better ideals on which my country was founded and at the same time judge its leaders independently. Patriotism didn’t equal blind loyalty to any president.

This is what I hope today’s Boy Scouts are able to figure out. Even if the adults in their lives don’t understand it themselves. Politics, after all, is nothing more than an argument about the ideas we use to organize our government. It’s not about cheering for a team, and it’s not—despite what Donald Trump seems to think—about applauding one man’s ambition for fame and power. I know it’s idealistic to expect this, but I hope at least some of those Boy Scouts will read Johnny Tremain. I hope they’ll go see Hamilton, or listen to its soundtrack. I hope they’ll read the works of our founders—and their critics. And then I hope they’ll look back and wonder what Trump was up to in that speech, and why they applauded him, and what they really want in a president, a Congress, a country.