The death-positive movement is being built around activism, science, entrepreneurship, art and feminism. Can it remove the stigma from mortality?

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

In the back of our minds, we all know that only one thing is certain in life: We are going to die. In the front of our minds, though, we push this thought away, calling it morbid, and somehow try to convince ourselves it won’t happen to us. Death remains one of the greatest taboos in Western culture; we don’t talk about it, we don’t prepare for it and very few of us handle the dead. But a growing movement of death-positive activists are trying to alter this aversion, and, increasingly, these walking memento-mori’s are women.

It’s easy to think that the presence of women around death is strange. For the past 150 years, doctors, morticians, and funeral directors have largely been men. But it wasn’t always like this. Out of necessity, death and mourning used to take place in the home, and, like birth, the preparations for both were handled by women. Matriarchs cared for the dying, and prepared the bodies after death: washing them, dressing them and ultimately handling the memorial.

During the Civil War, however, everything changed. Men were dying away from home en masse, and to ensure that families got to see their loved ones before burial, doctors began embalming the bodies and sending them home. And what started as an ill substitute became a business: Embalmers set up shop near battlegrounds and sold soldiers their own corporeal afterlives. Death became a commodity, and more men wanted in on it. Suddenly families could buy coffins and burials and entire funerals, and a new paradigm was born.

Simultaneously, the advent of the modern hospital led to death being treated as an illness. The dying were taken out of the home, and, with few exceptions, women were pushed into the sole role of mourner. And with this, death became sanitized, synthesized and stigmatized. The modern funeral rose to dominance, and the gap between ourselves and our mortality widened.

It’s this gap that women today are trying to close. Over the past decade, more women have entered the standard death industry (57 percent of mortuary-science students are now women), but more than that, women are spearheading the effort to re-naturalize dying, and take death back from the $16 billion-dollar industry. Called death positive, death acceptance, or death literate, this movement is working to change everything from how we talk about and prepare, to where we die, how we’re interred, and where our final remains go. In short, while reclaiming a place for women in death, these women are simultaneously changing the way we die.

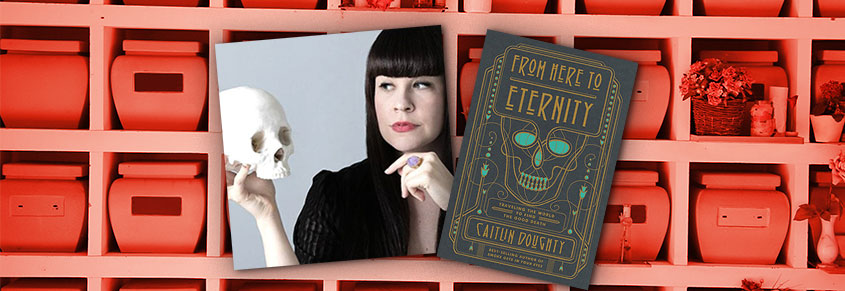

The unofficial leader of this movement is Caitlin Doughty, the darling of death who rose to fame years ago with her popular YouTube series, “Ask a Mortician,” and subsequent book Smoke Gets in Your Eyes,” both of which aimed to demystify the world of the undertaker. In 2011, Doughty founded the Order of the Good Death, a collective of death savants working to bring discussions of mortality back into the public sphere and expel the long-held fear of death. The collective is 80 percent women, all of whom are building a revolution of death awareness through activism, science, entrepreneurship, art and feminism.

The Order’s director, Sarah Chavez, is also the founder of the blog and community Death and the Maiden, which focuses on the historical and contemporary connection between women and death. Death and the Maiden was formed almost by accident after a panel at Death Salon, an annual gathering that centers around “conversations on mortality and mourning and their resonating effects on our culture and history.” Titled “Death and the Feminine,” the panel’s audience was almost exclusively female-identifying, a fact that got Chavez and everyone else thinking.

“There was a lot of discussion like, ‘Look around the room. It’s 95 percent women. Why is that?’ And so this conversation, this question and observation kept coming up over and over and over again,” she said. “I was really interested in the question of, why? Why are there so many women involved in and interested in death right now? I wanted to be able to explore that and then create a place for self-identified women to be able to have their voice.”

The result was Death and the Maiden, which just held its first convention in the U.K. and continues to explore the question: Why women? And why now?

There are many theories circling this question. A common one is the idea that women are naturally more “nurturing” and “maternal,” but most of the women in this movement reject this stereotype. Instead, the reality is more nuanced and progressive. At its core, this movement is built on the notion that the way we die today is environmentally and psychologically unsound. And while primarily men have spent decades profiting from normalising this system, as relative newcomers to the industry, women are equipped to see an alternative route.

For Chanel Reynolds, this path starts long before death. Tellingly, over 50 percent of the population doesn’t have a will or an advance directive, a reality that made Reynolds’s life all the more difficult when her husband was struck by a van while riding his bike and killed without the couple having made final arrangements. On top of her grief, Reynolds had the added stress of figuring out how to access bank accounts, worrying about their two-income mortgage, losing her medical insurance and more. After spending months sorting out what could have taken just days, Reynold’s wanted to make sure no one else went through what she did. A few years later, she founded Get Your Shit Together, an online service to help guide people through the process of preparing financially and legally for death.

“The suffering that you feel when you lose someone you love, you can’t get away from that,” she said. “But the suffering that you feel when you’re worried about losing the house and you’re worried about how you’ll pay your bills, those things don’t have to make an already hard time harder.”

Reynolds also believes that in our society, women are more prone to taking on this “optional suffering,” as she calls it, and therefore sees the act of “getting your shit together” as a potentially feminist one.

“As women who get paid 80 cents on the dollar, who end up doing the majority of the child care and the elder parent care, and who find their financial standing in decline after a divorce, we’re already more vulnerable,” she said. “So when hard times hit, and we’re not financially prepared, we are often the ones that bear the brunt of that the hardest.”

In a nod to the way we used to die, women are also the ones advocating for bringing death away from the medical industry and back into the home. Up-and-coming progressive funeral parlors, like Doughty’s Undertaking L.A., offer in-home services, and women across the country are also training to be death doulas and midwives, acting as facilitators both for the dying and the ones left behind.

The home death movement often intersects with the green or eco-burial movement, which is also being led by women. In addition to stripping death of its natural process, conventional burials and funerals are also hugely unsustainable. Every year, Americans bury 180 million pounds of steel, 5.4 million pounds of copper and bronze and 30 million feet of hardwood in the form of caskets, as well as 3.3 billion pounds of reinforced concrete and 28 million pounds of steel in vaults, according to a study from Cornell University. Additionally, the 827,060 gallons of embalming fluid—which includes formaldehyde—we bury each year has made the pastoral, seemingly natural setting of the cemetery a toxic wasteland, and has degraded the health of undertakers for years. The only other conventional option—cremation—is not much better: The Funeral Consumers Alliance estimates that 246,240 tons of carbon dioxide are released into the atmosphere each year due to cremation, or the equivalent of 41,040 cars.

In a green or eco-burial, all of this waste is avoided, and rather than becoming a burden on the environment, the dead foster new life: In addition to forgoing embalming, bodies are buried in either renewable wood, woven willow or wicker caskets, or wrapped in raw cotton, linen or even paper, all of which decompose with the body. There are no vaults, and the bodies are placed in nature preserves or sanctuaries, effectively protecting the environment rather contaminating it. Green burials are also significantly cheaper than a conventional funeral, which start around $8,000 in metropolitan areas, not including a burial plot. Green burials cost an average of $6,700 with plot included.

Doughty’s Undertaking L.A. is just one of the many women-run funeral homes participating in this type of burial. Ellen Macdonald is the owner of Eloise Wood, Central Texas’s only natural burial cemetery; Nora Menkin is the Managing Funeral Director of the Co-op Funeral Home of People’s Memorial in Seattle, one of the only not-for-profit funeral homes in the country, which also offers green burials, and Shelia Champion launched the first green burial ground in Alabama in 2015. And that’s just to name a few.

Green burial isn’t new, but progressive women in this space are pushing the movement even further into eco-consciousness. Jae Rhim Lee, an artist, designer and researcher, created the Infinity Burial Project, a bodysuit woven from a unique strain of edible mushroom that decomposes and remediates the toxins in human tissue, removing the residual chemicals bodies can leak into the environment. And Katrina Spade founded the Urban Death Project, which is in the pilot stage of creating a new system of burial called recomposition, which transforms bodies into compost. The Project will center around an urban building where families will bring their loved one, take part in the first steps of the composting process, and eventually come back and collect some of the dirt to plant a living memento-mori.

Additionally, the green burial movement is spawning a newfound desire for death garments, wraps and shrouds, which were traditionally used to bury the dead. And while a simple, natural-fiber sheet does the job, fashion designer Pia Interlandi takes it a step further with her line Garments for the Grave—instead of designing a one-size-fits-all wrap, Interlandi works with each client to create a custom garment, imbued with meaning. Families get involved in the process, too, adding decorations and details to the garment that hold significance, giving them a way to engage with the death they’re a part of.

“It’s not just the garment. It’s the consultation that goes along with designing it. We talk a lot about their life, their death, what they love,” she said. “You’re using a piece of fabric as a tool to bring people closer into death.”

Sometimes Interlandi dresses her clients, and sometimes they have traditional funerals, but she encourages the family to be as involved as possible, keeping their loved one at home for up to five days to witness the body readying itself for burial, then preparing and dressing their loved one themselves. And to her, the catharsis that comes from this is the crux of the process.

“Coming in and seeing a body without life in it, I think mentally fills a gap,” she said. “And that’s why I think it’s so important. Bodies aren’t scary or dangerous or disgusting; they’re just dead. And we don’t know what that looks like anymore.”

Imbedded in this act—and in every element of this movement as a whole—is an attempt to restore ritual. As our culture has become more secular and death further removed from our conscience and life, we’ve lost the comfort of rite. With that, each death is unchartered territory, and we’re stuck without a map. As Reynolds put it: “Grief is already so overwhelming and isolating and all-encompassing. It would be kind of nice in some way if there was a feminist version of knowing where to go and where to put your hands, almost.”

This is perhaps the most important element of what Interlandi and Chavez and Doughty and the Order of the Good Death and Death and the Maiden and all these women are trying to do: It’s not just about disrupting a male-dominated industry, or even about reclaiming a place for women in death; it’s about changing the way we perceive mortality, and cultivating a healthy relationship to it. It’s a long-held taboo that is hard to break, but these women see the cracks showing.

“We are on the cusp of the next wave and everyone’s felt it coming,” Interlandi said. “Everyone on the ground knows they’re doing something that is right and they feel the importance of it. It’s not mainstream by any means, but there’s something in the air that’s coming.”