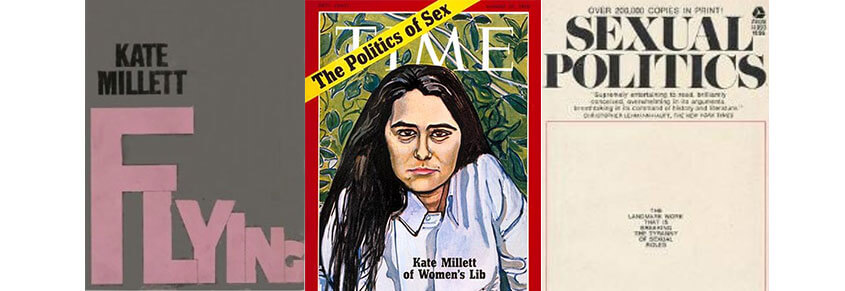

The author of such groundbreaking works as ‘Sexual Politics’ and 'Flying' showed a generation of women how to resist—through her writing, her activism, and by example.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Although less of a household name than Betty Friedan or Gloria Steinem, feminism owes much to Renaissance woman Katherine “Kate” Millett, the prolific and erudite writer, artist, and activist who passed away on September 6, 2017, just shy of her 83rd birthday. Like so many feminist trailblazers, Millett paved the way for a number of privileges we now largely take for granted, including the very existence of feminist literary criticism.

Kate Millett’s writing, the work for which she was best known, was fearless, angry, at times droll, and sharp. Her most influential book, Sexual Politics, was based on her Ph.D. dissertation and influenced by another cornerstone of feminist thought, Simone De Beauvoir’s The Second Sex.

In the late 1960s and into the 1970s, women earned just slightly more than half what their male counterparts. They had limited reproductive rights, limited access to high-paying jobs, and severely limited political representation. Yet noting that women were relegated to second-class status was not yet an integral part of intersectional literary criticism and progressive social commentary.

In Sexual Politics, which was published in 1969, Millett deconstructed the overt misogyny in the works of so-called literary lions Henry Miller and Norman Mailer—something for which we can all be grateful—as part of a larger takedown of how patriarchal norms are woven into the fiber of the art we consume. “Many women do not recognize themselves as discriminated against; no better proof could be found of the totality of their conditioning,” she wrote.

Perhaps even more radically, Millett called for an end to monogamous marriage and compulsory childbirth. She labeled romantic love “a means of emotional manipulation which the male is free to exploit,” and advocated for the types of open lesbian relationships she maintained during her first marriage to the (male) sculptor, Fumio Yoshimura.

Sexual Politics was published only a year before Shulamith Firestone’s equally groundbreaking The Dialectic of Sex, both of which became foundational texts of radical second-wave feminism. The two thinkers were friends, and Millett once noted that if Firestone’s celebrity sometimes overshadowed hers, it was because they were both offering pointed, polarizing critiques of popular culture that, even as their books climbed best-seller lists, was ridiculed by mainstream media outlets. “I was taking on the obvious male chauvinists,” Millett told journalist Susan Faludi after Firestone’s 2013 death. “Shulie was taking on the whole ball of wax. What she was doing was much more dangerous.”

Writing the afterword for a new edition of Sexual Politics in 2016, The New Yorker’s Rebecca Mead explains the “remarkable fact that re-reading Sexual Politics now brings to light is this: that at the time it was written, literature was agreed to be something worth fighting over.” If literature remains worthy of a brawl—that is, if a functioning democracy depends on our collective resistance against outmoded ideas about civil rights, including rights related to gender and sexuality—Millett’s groundbreaking work is certainly part of the reason why.

During a time when many queer women felt compelled to stay in the closet, Millett was openly bisexual. The decision to be out was professionally tricky, as she noted that being openly lesbian made her “an invalid spokesperson” among American intellectuals of the era, primarily in the women’s liberation movement. “Never queer enough for the fanatic,” she wrote in her 1974 memoir, Flying.

Hers was an impressive academic pedigree, including a Ph.D. from Columbia University and a master’s degree from Oxford University’s St Hilda’s College, where she was the first American woman awarded first-class honors for postgraduate work. Yet in this wonderful archive episode of Lesbian Central, in a conversation between Millett and another groundbreaking lesbian intellectual and gifted, prolific writer, Sarah Schulman, Millett notes of coming out, “I was marginalized as a writer and as an intellectual … and because I was a political activist, I was kind of marginalized in the literary thing.”

Despite her contributions to women’s liberation and feminist thought, she was marginalized in numerous ways. When her supposed sisters in arms insisted she come out as bisexual, she was shunned by fellow lesbian rights activists and experienced a breakdown that ended with her committed to a mental institution. She details the experience in Flying and The Looney-Bin Trip, and told Faludi, “We [feminists] haven’t helped each other much … haven’t been able to build solidly enough to have created community or safety.”

In acknowledging this problematic history of movement marginalization, though, I still don’t reflect on Millett as a woman who sat on the sidelines, even when she was at times rejected and estranged from the mainstream women’s movement. She wrote thoughtfully and wisely about a range of topics daunting to today’s intellectuals: Iranian women’s rights, state-sanctioned torture, and the politics of psychiatric treatment and pharmaceutical drugs, the latter a reflection of her time spent involuntarily institutionalized.

Summing up one’s life by cataloging vast literary achievements risks missing other accomplishments. Millett was a talented sculptor and silkscreen artist. She was a bold, thoughtful filmmaker, known for several films including her “moving, proud, calm, aggressively self-contained” 1971 documentary, Three Lives, which boasted an all-female crew, something that remains notable nearly five decades later. Before hurtling to fame as a writer, she was an activist, noted as a member of influential feminist organizations including New York Radical Women and the National Organization for Women (NOW).

It’s only possible in retrospect, but today, I see Millett’s work as defining so much scholarship and activism that followed her example. In one acclaimed work, Sita, Millett chronicles the disintegration of her relationship with a woman ten years her senior, capturing a crucial piece of queer history in an era when lesbian relationships were not so conspicuously and thoughtfully documented. She also wrote an entire memoir, Mother Millett, about the role reversal of caring for her dying mother.

“I think I was always a feminist. There just wasn’t any place to put it for a long time,” Millett said in the 1980 documentary, Some American Feminists, about discovering the women’s liberation movement and finding a place therein. Thanks to women like Millett and the work she gave us, we all have places where we can locate our politics, literature and films that help us identify and name our values, and meaningful historical work of integrity on which we can base our lives and carry on the legacies of those who have helped us reach this juncture in our history.