In an election marked by economic message failures and false promises, Sarah Jaffe asks, in this excerpt from ‘Nasty Women,’ whether we can ever find the solidarity to move us forward.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

On March 8, dozens of red-clad women marching to the tune of “Bread and Roses,” the hundred-year-old labor song associated with women’s workplace struggles, converged on downtown Lafayette, Indiana, bearing signs that read “I strike for labor rights, I strike for full social provisioning, and I strike for anti-racist and anti-imperialist feminism.” They spoke into a megaphone, declaring their intentions to the city, a part of an international action that in the United States largely took aim at the administration of Donald J. Trump.

The Trump administration has done its best to prove the age-old labor adage that “the boss is the best organizer.” Its attacks on multiple vulnerable populations right at the outset drove millions into the streets, pushed thousands into joining or creating new political organizations, and turned many occasional voters into die-hard activists declaring themselves part of the resistance.

Since Trump resembles nothing so much as a tyrannical boss (after all, his signature line before “Make America Great Again” was “You’re fired”), it shouldn’t be surprising that labor terminology and tactics have similarly seen a revival. When the executive order banning immigrants, travelers, and refugees from seven Muslim-majority nations was released, thousands rushed to their local airports to demand that detained travelers caught in transit be allowed entry. But one group of people went further. Taxi drivers, who usually line up at cab stands at New York City’s major airports waiting for fares, went on strike, refusing to take fares from John F. Kennedy Airport.

Members of the Taxi Workers Alliance, which called the strike, are overwhelmingly Muslim and Sikh and often face violent attacks at times of increased Islamophobia, according to the alliance’s executive director, Bhairavi Desai. “Already, drivers are twenty times more likely to be killed on the job than other workers,” she said. “We are one of the most visible immigrant and Muslim workforces. Our members tend to be on the frontlines of that hate and violence.” Such workforces as the taxi drivers, made up of people of color, immigrants, and women, live at the intersections of the violence of Trump’s proposals.

The drivers’ strike was greeted with an emotional outpouring of support across the country—a nation that is largely disconnected from workers’ struggles, as both union membership and the frequency of such strikes have plummeted over the past few decades in the face of right-wing attacks on workers’ rights. Despite that disconnect, Americans were outraged when Uber, the so-called sharing economy ride-hailing app, announced it was turning off its infamous “surge pricing,” dropping rates in what protesters perceived as an attempt to break the strike. #DeleteUber trended; The New York Times reported that 200,000 people did so in response to Uber’s scabbing. Solidarity, that age-old labor movement value, was alive and well.

The enthusiasm for the taxi drivers’ strike helped to amplify the calls for another, bigger strike that had been building since before Trump was sworn into office. The general strike is labor’s sharpest and strongest weapon, an attempt to shut down an entire city by having all workers refuse to work. It can be the ultimate act of solidarity, and it can be—as it has been framed in Trumplandia—a way of making demands on the state. As Rosa Luxemburg wrote in The Mass Strike, such a strike is spurred by historical conditions, becoming possible when it seemed impossible, reversing the power dynamics of society, combining economic and political struggle.

The term was brought back to public consciousness in the Obama era, first during the Wisconsin (and then Ohio and Indiana) labor uprisings of early 2011. In those moments, the idea of workers refusing to work was in response specifically to an attack on union rights, on the women and people of color who make up the majority of the public-sector workforce nationwide, the teachers and social workers and nurses who lost their collective bargaining rights under Governor Scott Walker’s Act 10. The massive protests in Madison, Wisconsin, brought hundreds of thousands to the “People’s House,” their term for the capitol, in what might have tipped over the edge into a general strike. The Occupy movement seized on the idea of a general strike next, first in Oakland, California, when longshore workers and others acted in solidarity with the Occupiers who had been evicted from their camp and shut the port and a variety of other businesses, and then nationwide for actions on May Day, the holiday celebrated as International Workers’ Day in most countries outside of the U.S. (despite the day’s roots in a massive general strike for the eight-hour workday in Chicago, in 1886).

The Chicago Teachers Union called something akin to a general strike on April 1, 2016, bringing the low-wage workers of Fight for $15, organizations aligned with the Movement for Black Lives, and community organizations across Chicago out with them in a massive day of action for public schools and public services, demanding the city and the state pass a budget that funded education, raised wages, and shifted spending away from prisons and police.

But many of the calls for a general strike against Trump came from those more disconnected from the struggles of the working class. Famed novelist and scholar Francine Prose wrote in The Guardian in praise of disruptive protest, noting, “The struggles for civil rights and Indian independence, against apartheid and the Vietnam war—it’s hard to think of a nonviolent movement that has succeeded without causing its opponents a certain amount of trouble, discomfort and inconvenience.”

Prose was correct that power, to steal a frame from Frederick Douglass, concedes nothing without disruption. But when she called for a “general strike” she showed a lack of understanding of just what a general strike actually is. “Let’s designate a day on which no one (that is, anyone who can do so without being fired) goes to work,” she wrote. Such a framing has been echoed elsewhere, as people call for a strike-that-isn’t-a-strike. After all, if the boss gives you permission to stay home, you’re no longer on strike.That’s not to take away from the importance of business owners who shuttered their shops in solidarity with strikes like February 16’s Day Without an Immigrant or the Yemeni business owners who closed their stores on February 3 to protest the Muslim ban. But it is to say that a strike without risk is not much of a strike. And a strike of those who can strike without risking being fired is likely to leave out the very people who will suffer the most from Trump’s regime. As Luxemburg argued, “If the mass strike, or rather, mass strikes, and the mass struggle are to be successful they must become a real people’s movement.”

This very disconnect among liberals from the struggles of working people was evident from the beginning of Hillary Clinton’s campaign for the presidency, and was a key reason why Donald Trump was able to beat her. The Democratic Party’s decision to turn to Wall Street and the wealthy for funding decades ago mirrored a corresponding policy shift toward “free trade” deals that ship jobs to wherever the wages are lowest and the regulations fewest, crunching both working people in the U.S. and abroad, and helping to spike xenophobic beliefs about foreign-born workers. The disappearance of the wages and benefits that generations of workers had struck and struggled for fueled a deep-seated rage that Washington political insiders were totally unprepared to deal with. A protest movement that reinscribes those same mistakes rather than learning from them is one that is doomed to come up short again.

Prose and many others who deleted Uber simply switched to Lyft, a company that may not have publicly scabbed on a strike and that quickly moved to donate to the ACLU to burnish its image, but which relies on the same business model as Uber—one that requires its workers to bear all the costs of their job while controlling their movements and setting their fares. A job action might have incited the #DeleteUber move, but the indifference of so many to previous criticisms of Uber and Lyft underlines the class split within the anti-Trump movement.

Clinton’s refusal on the campaign trail to endorse a $15-an-hour minimum wage—even while courting the fast-food workers’ movement, a movement made up primarily of black and Latinx workers, a majority of them women—continues to rankle. The unexpected challenge of Bernie Sanders to Clinton’s left heightened the focus on her past support for welfare “reform” and NAFTA, her proposals to potentially reduce Social Security benefits, her hedging on wages and college debt, and her outright refusal to consider single-payer health care. And since the election, prominent Clinton aides like Jennifer Palmieri, who told MSNBC’s Chuck Todd that “you are wrong to look at these crowds and think that means everyone wants $15 an hour,” have continued to sound that sour note. Palmieri’s defense of “identity” politics continued: “I support you, refugee. I support you, immigrant in my neighborhood. I want to defend you. Women who are rejecting Nordstrom and Neiman Marcus are saying—they’re saying this is power for them.”

Thankfully, the protests are not simply made up of the Nordstrom class, and the biggest wins for the disparate movement known simply, most of the time, as the Resistance came largely from the people for whom avoiding Neiman Marcus is not a choice. (Lest we forget, some 42 percent of the country would get a raise if the minimum wage was raised to $15 an hour; the top 1 percent, meanwhile, owns about 40 percent of the nation’s wealth.)

The workers of the Fight for $15 brought down Andrew Puzder, CEO of the company that owns Hardee’s and Carl’s Jr. and accused spousal abuser. The nomination of Puzder to run the Labor Department seemed like the punchline on the string of bad jokes that were Trump’s cabinet nominations. In the wake of a massive movement around the country demanding higher wages and union rights, kicked off in 2012 by fast-food workers in New York City, putting a fast-food CEO in charge of the department that regulates labor practices was nothing less than a giant “fuck you” to American workers. And Puzder’s withdrawal from the process—because, according to an anonymous source, “He’s very tired of the abuse”—was a victory for those same workers, who went on strike and rallied around the country against his confirmation. Worker organizations maintained that Puzder’s restaurants had sexual harassment rates 1.5 times higher than the already-sky-high 40 percent rate of harassment in the fast-food industry as a whole, and made the connection to the company’s sexually suggestive ads. “Customers have asked why I don’t dress like the women in the commercials,” one Hardee’s employee told researchers. Puzder’s response to criticisms of the ads was that “We believe in putting hot models in our commercials, because ugly ones don’t sell burgers.”

While sexual harassment is often painted in the media and in fiction as a barrier that women face on their way to shattering glass ceilings, the fact is that the people more likely to endure it are working- class service employees, who also struggle with wage theft, forced overtime, and lack of paid sick time. Service industry jobs are dominated by women, people of color, and immigrants—those facing multiple attacks from Trump’s proposed policies, from crackdowns on abortion rights to deportation to violence from emboldened police forces that mostly endorsed the president.

But as political scientist Corey Robin notes, the location where most people face routine oppression and denial of their rights is the workplace. Puzder’s labor record is just another stark reminder of that fact—as is the tendency for Immigration and Customs Enforcement to raid workplaces to round up undocumented workers, sometimes with the collusion of employers who want to get rid of pesky employees who might have tried to organize a union or make some demands. This is why so many of the protests against inequality and austerity during the Obama era kicked off with demands for union rights or against the denial of those rights, and why the idea of a general strike against Trump hovers in the collective consciousness.

It might seem ironic that a perceived attention to workers’ needs is what put Trump in the White House, yet on the campaign trail he continually slammed Clinton for her ties to Wall Street and her support for trade deals, while promising to bring back manufacturing jobs to the U.S. Reporters continue to assert that Trump’s base is the “white working class,” and though the truth is far more complicated than that simple narrative, it is telling that the “white working class,” to most people who discuss it, is little more than another identity box: white men who work in manufacturing and wear baseball caps like the one Trump ostentatiously paraded around in on the campaign trail (and continues to sell to supporters).

But class is not, as I have written elsewhere, a baseball cap. It is a relation of power; it is one’s position in the economy and the world. It is shaped by one’s gender and race and immigration status; one’s sexuality, gender expression, and ability, and many other things besides. To understand this, think about the fact that transgender women of color face the highest unemployment rates in the country and are regularly criminalized for simply existing in public, making it even harder for them to find legal work and creating a vicious cycle of poverty and prison. Caring about class, then, means understanding that bills to deny trans people access to restrooms will affect their economic conditions, throwing them out of work and impacting the economic and political power that they have.

That Trump’s lip service to class concerns was something that some working people wanted to hear desperately enough to believe a billionaire shows how bad things have gotten. In Wisconsin, where labor battles have been central, Hillary Clinton’s inattention amounted to campaign malpractice. The swing toward Trump in locations like Waterford, New York, where a hundred-day strike at the Momentive chemical plant saw workers huddled over burn barrels to stay warm on the picket line most of the winter, was not complete, but it was enough to flip a district that had voted for Obama into the Trump column. Lip service, or as Indiana organizer Tom Lewandowski told me, “emotional representation” was better than the tone-deaf “America is already great!” messaging that offered the status quo with a couple of tweaks around the edges. Trump echoed back at them the anger of working-class men who felt their purpose dwindling with their paychecks, that anger twisted to blame the less powerful rather than the boss—who might, as had been the case at Momentive, be one of Trump’s buddies, after all. Economic concerns shaded all too easily into xenophobia and racism, as Mexican workers took the blame for jobs departing or being filled by more exploitable immigrants. And the willingness of some Democrats to use Islamophobic rhetoric against Muslim-American congressman Keith Ellison when he challenged for the Democratic National Committee chair position should remind us all that Democrats have not been blameless when it comes to race-baiting. But Trump’s promise to shred trade deals that have contributed to the disappearance of industrial jobs, coupled with bragging about his ability to bring jobs back, and even the occasional nod in the direction of needs like paid family leave, has come to little. He has nothing to offer but attacks for the vast swathes of the working class who are not white men, and even his promises to those white men have proven to be not worth the pixels in the misspelled tweets, as the overhyped deal to “save” the Carrier furnace plant in Indianapolis should remind us. His meetings with high-profile building trades union leaders resulted in nothing but photo ops for the union leaders to take home to their members as they explained that the new president who claimed to care about working people was likely to shrug as the regulations that set prevailing wages for construction work are swept away. And when United Steelworkers Local 1999 president Chuck Jones pointed out the mass layoffs that would continue at Carrier, Trump sent a frenzied series of tweet attacks aimed at Jones.

Settling for lip service is a relatively new state of being for white male factory workers, who are largely not interested in moving into the service jobs that are the fastest-growing part of the economy. After all, lip service has historically been about all that service workers can expect for their hard work—at Walmart, as historian Bethany Moreton detailed in her book To Serve God and Wal-Mart, the women who made Sam Walton’s fortune for him were recruited specifically because they were unlikely to demand higher wages or unions. Walton and his managers skillfully played on the women’s values in order to win their loyalty while picking their pockets and passing them over for promotions. (When pressed to show that he valued women, instead of giving a raise to his existing employees, Walton recruited a local attorney and then–First Lady of his home state to join his company’s board: Hillary Clinton.)

But Walmart remains the world’s largest private-sector employer, and the demands of its workers, like Venanzi Luna, should be central to today’s progressive movements if they intend to actually challenge not just one individual bad boss in Donald Trump, but actually fight for a more equal world. Venanzi Luna lost her job when Walmart closed down the store where she worked, in Pico Rivera, California. The store had been the site of the first-ever strikes at a Walmart retail store back in the fall of 2012, and Luna had been one of the leaders in the store, which became a hotbed of activism. In the spring of 2015, I watched as Luna confronted Walmart’s CEO Doug McMillon on the floor of the company’s shareholder meeting, asking him to prove that she hadn’t lost her job because of her strike leader- ship. McMillon oozed sympathy, but made no promises.

It is women like Venanzi Luna who are in the crosshairs in Donald Trump’s America but were largely forgotten even in Barack Obama’s and Bill Clinton’s. The risks she took are the same risks that built the labor movement, which in turn created a stable American middle class for decades. Luna risked her job to walk out on strike; years later, in a very conscious echo of the famed Flint sit-down strikes that helped set the cornerstone of industrial union power, she sat down with tape over her mouth in the middle of a Walmart. Luna, whose job barely paid her enough to shop at the Walmart she worked in, much less Neiman Marcus, was willing to risk losing her job and being arrested to win decent wages and a reliable schedule. Venanzi Luna and her comrades remind us that those factory and construction and mining jobs Trump pledges to bring back were not “good” jobs because of some inherent characteristic of the work or the benevolence of bosses—they were good jobs because workers had fought, struck, and even died to organize unions.

It is to Luna’s example that we should look if we want to talk about strikes and disruption to stop Trump. As many commentators have noted, Trump’s presidency seems often designed as nothing more than an operation to siphon wealth to Donald Trump. This is more blatant than we are used to, but it is nothing new in American politics, which have become little more than a machine for creating inequality, stripping working people of our rights and the public goods that our taxes are supposed to fund while funneling that money instead into the hands of the already wealthy. To stop this machine, people will have to refuse any longer to grease it with their labor and in fact to put their bodies in its way.

We must become comfortable with the idea of risk, the way Venanzi Luna did.

This is not to say that resistance cannot be fun—indeed, disruption, as the Tea Party protesters discovered under Obama, can be tremendous fun. But it can also be dangerous, and not grappling with that fact—and not grappling with the fact that danger is not equally distributed—will spell disaster for the movement.

After the Women’s March on January 21, some crowed at how peaceful the marches were, thanked police for support, and cheered women-led movements for avoiding arrest. Yet the protesters in Ferguson, Missouri, in the summer and fall of 2014 did not get the option to peacefully take to the streets and hug it out with the cops; their public mourning for teenage Michael Brown, shot dead in the street by one of those police officers, was interrupted by the National Guard—the same National Guard that Trump was rumored to want to send out to round up undocumented immigrants.

The violence around a movement, in other words, is not based on the movement’s conscious decision or its gender makeup (the Ferguson movement and the broader Movement for Black Lives were led in large part by young black queer women), but on the perception of its participants by those in power. Young black people in the street chanting “Hands up, don’t shoot!” heroically faced down police in armored vehicles aiming assault rifles at them. Today’s resistance must prepare itself to do the same.

Direct action involves risk. The water protectors at Standing Rock locked themselves to construction equipment to stop an oil pipeline being drilled underneath their water source. In New Mexico, when Guadalupe Garcia de Rayos was loaded on a van to be deported by immigration officials, Maria Castro and seven others were arrested trying to physically block the van’s departure. “The van literally pushed me at least 30 feet, hyperextending my knees, hurting some of my friends, knocking some of my fellow organizers down to the ground,” she told me. “Another person started to hug the wheels and put his own life at risk, because this is just the beginning. This is the beginning of the militarized removal of our communities, of our families, and of our loved ones.”

There has been some handwringing about the lines that constitute “peaceful” or “nonviolent” resistance; debates over everything from the punching of avowed white supremacist Richard Spencer to the blocking of Internet troll and Trump supporter Milo Yiannopoulous from speaking have raged, with someone always bringing up the specter of “playing into their hands” by crossing some imagined lines. These actions get deeply gendered; a criticism of them is nearly always that they are “macho bullshit,” signifying nothing.

There is some truth to this—Trump is not likely to be dethroned by a broken Starbucks window. And yet in considering what resistance looks like, I would caution against cheering for marches that win hugs from police and frowning at a thrown brick. Marsha P. Johnson’s brick that (apocryphally) began the Stonewall Riots was an act of love for her community, not posturing, and the man who wrapped his arms around that car tire may have been dragged off to jail, but he, too, was expressing his love for Garcia de Rayos even as she was taken away.

With this understanding, a group of feminist organizers called for a women’s strike on International Women’s Day, March 8, 2017, to be a catalyst for building “a feminism of the 99 percent,” one that puts violence into context with work. In a piece also published in The Guardian, Linda Martín Alcoff, Cinzia Arruzza, Tithi Bhattacharya, Nancy Fraser, Barbara Ransby, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, Rasmea Yousef Odeh, and Angela Davis wrote, “The idea is to mobilize women, including trans women, and all who support them in an international day of struggle—a day of striking, marching, blocking roads, bridges, and squares, abstaining from domestic, care and sex work, boycotting, calling out misogynistic politicians and companies, striking in educational institutions. These actions are aimed at making visible the needs and aspirations of those whom lean-in feminism ignored: women in the formal labor market, women working in the sphere of social reproduction and care, and unemployed and precarious working women.”

On March 8, women in red and their supporters took to the streets around the country to make this vision a reality. Three school districts, Alexandria city public schools in Virginia, Prince George’s County public schools in Maryland, and the Chapel Hill–Carrboro school district in North Carolina, were closed down for the day because so many teachers—a profession, again, dominated heavily by women—stayed home from work. The women of the Walmart campaign joined hundreds of others in Washington, D.C., for a “Women Workers Rising” event alongside the women of the National Domestic Workers Alliance and other service workers, centering the gendered labor that women do. In New York, several women were arrested forming a human chain around Trump Tower, including Linda Sarsour and Tamika Mallory of the Women’s March on Washington planning committee. They joined women around the world, including in Ireland, where abortion remains illegal; women shut down the center of Dublin to demand the repeal of the Eighth Amendment and the granting of the right to an abortion.

Debates around the strike hemmed and hawed around the issue of “privilege,” but the women who turned out on March 8 were working women whose struggles in the workplace were intimately connected to their political struggles. For the decades of the early labor movement, this was understood as basic fact, that strikes could be used to win larger political goals as well as gains in individual workplaces. To move forward in the Trump era, such an understanding will be necessary again, an understanding that draws on the bedrock principle of the labor movement—solidarity. That solidarity does not mean we are all the same, or that we all face the same challenges or have the same levels of power. But it means that we understand our struggles as connected and understand that a winning movement must use the power and talents we all possess in order to bring about justice.

It means that we are willing to take risks together, because our liberation is bound up together.

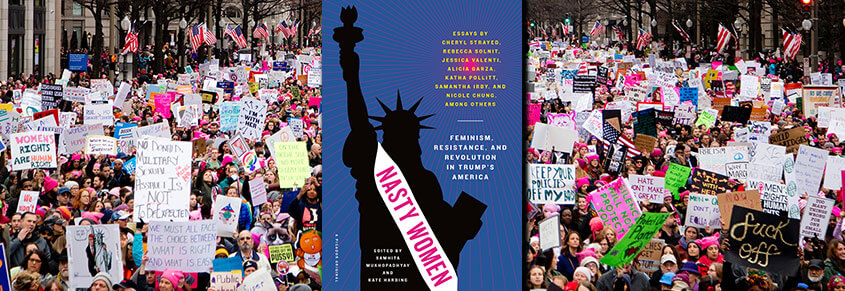

Excerpted from NASTY WOMEN, edited by Samhita Mukhopadhyay and Kate Harding. Published by Picador. Copyright ⓒ 2017 by Samhita Mukhopadhyay and Kate Harding. All rights reserved.