Michigan is just the latest state to consider this fathers'-rights-supported measure, which, despite the euphemistic name, poses a big problem for victims of domestic violence.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Michigan is considering a shared parenting bill, promoted by fathers’ rights groups, which, as drafted, could be detrimental for victims of domestic abuse.

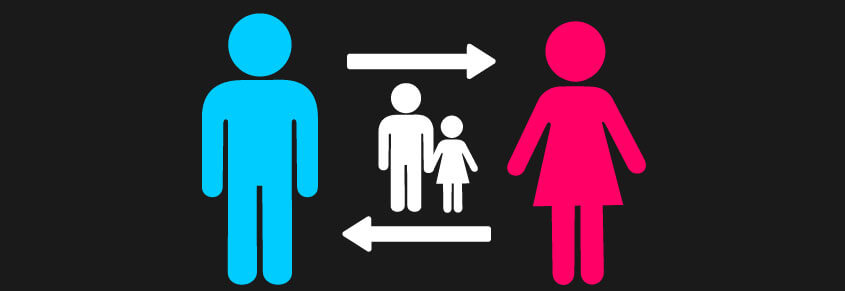

The bill would require family courts to grant joint legal custody and equal parenting time in custody disputes and divorce. HB 4691 made it out of committee this past summer and is awaiting a hearing in the house. The bill would essentially shift custody decision-making standards from centering the “best interests” of the child to centering the rights of parents. While touted as an equal-parenting initiative, the efforts are spearheaded by father’s rights groups who say that dads don’t don’t get a fair shake in family court. The bill has judges, lawmakers, and domestic abuse advocates concerned about the implications that these blanket rules would have on victims of domestic abuse.

National Parents Organization is the organization that works to advance these shared parenting bills across the country. According to its website, the goal is “to make shared parenting the norm by reforming the family courts and laws in every state.” And, while it strives to maintain an egalitarian agenda of working for parents of all genders, it is a father’s rights group, the grown-up dad version of a men’s rights activist organization, as its original name, Fathers and Families, belies.

The agenda behind shared parenting legislation is important to understand because, while the language around the bills purports to emphasize the rights of both children and parents, these efforts are actually fueled by men’s rights activists who believe that they have been disenfranchised by women and feminism, and that distinction and framework in this discussion matters a lot.

Robert Franklin, the Board member who pens National Parents Organization’s blogs, calls feminism “that old bugaboo of women”; says that feminism has “characterized men as worthless abusers best avoided by women”; insists the gender wage gap exists as a function of choice, because “women place a greater premium on lower earning and greater time spent with their children” and that “public policy should treat that for what it is—women’s free choice, paid for by their male partners”; and calls child support “as much Mom support as anything.” He goes on in one blog to assert that the reason men aren’t listened to with regard to their views on family court or marriage and children is because of misandry and the devaluation of men in society.

In fact, historian Carol Brown has documented how our sense of who should have custody of children has largely been driven by economics throughout history. During the Industrial Revolution, when child labor was the norm and children had productive and economic value, society was largely in favor of men having sole custody should the parents separate, and sole control over children in general. As child labor laws forced children out of the workplace and they went from being an economic benefit to an economic risk, control gradually shifted to mothers. In her research on the “family wage” and the changing dynamics of American families, economist Heidi Hartmann wrote: “As children’s ability to earn money declined, their legal relationship to their parents changed . At the beginning of the industrial era in the United States, fulfilling children’s need for their fathers was thought to be crucial, even primary, to their happy development ; fathers had legal priority in cases of contested custody … Patriarchy adapted to the changing economic role of children: When children were productive, men claimed them; as children became unproductive, they were given to women.”

While people of all genders have had unfair experiences in the family courtroom, Cathy Brown, MS, Director of Victim Services for the Kalamazoo, Michigan, YWCA says that it’s typically men who come into these hearings with the most advantages.

“They usually make the most money so they can afford the best legal advice, they don’t have to worry about arranging for child care during the time of the proceedings, they more likely than not can take more time off from work.” And, when men already statistically hold economic advantage in divorce, arguing cases in court have the most financial ramifications on women.

Even without blanket rules that require judges to award equal parenting time, the shift away from awarding sole custody to moms has been increasing, as social norms change. Though not codified in law, gendered language is not used in most state’s guidelines, and the presumption in most states that adhere to “best interests of the child” guidelines is that kids benefit from the presence of both parents.

The shared parenting bill is purportedly a way to reform antiquated and biased family courtroom practices that consider moms as primary caretakers to be the default best interest of the child. But, Rebecca Shiemke, family law attorney specialist for the Michigan Poverty Law Program, says most parents come to agreements about custody on their own, without court intervention. And, she says, gender bias in favor of women in the family courts has not been proven by empirical evidence. In fact, she says, evidence shows the contrary.

A 2014 study that looked at child custody trends in Wisconsin found that over the course of two decades, the instances of mothers who were granted sole physical custody fell substantially. Between 1986 and 1994 mother sole custody fell from 80 percent to 74 percent, and by 2008 it had declined even further to 42 percent. Sole custody awarded to moms is actually in the minority today.

Only around 5 percent of custody arrangements are decided through family court trial. The rest are mutually agreed upon or mediated outside of a courtroom. Concerning to domestic violence advocates is the reality that among that small percentage battling it out in court are often abusers who are using the family courtroom as a means to further enact their abuse and control over their former partners. Brown says that the YWCA routinely sees clients who are going into hearings afraid to talk about what has happened to them for fear of retaliation.

The Report of the American Psychological Association Presidential Task Force On Violence And The Family says that “an abusive man is more likely than a nonviolent father to seek sole physical custody of his children and may be just as likely (or even more likely) to be awarded custody as the mother.”

According to statistics from the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, 1 in 3 women will experience some form of physical intimate partner violence. And while some men also experience violence at the hands of an intimate partner, 4 out of 5 domestic violence victims are women.

While statistics and men’s social privilege and power bear out that women are the primary victims of intimate partner violence, a big part of the men’s rights activist platform is the idea that men are the actual victims of domestic violence—that as many or more men are abused by their partners, and that men are often wrongly accused.

The proponents of the shared parenting bill say that victims of domestic violence will be protected and that exceptions will be made to the joint custody rule for parents who have a domestic violence history. But when the proponents of the shared parenting bill are the same activists who challenge the authenticity of domestic violence statistics, some find it hard to trust that assurance. Not only that, the logistics of that protection would be exceedingly challenging to enact.

The Michigan Judges Association Family Law Committee wrote a letter in opposition to the bill naming, among other things, concerns about the effects this law would have on victims of domestic abuse. “A parent with some domestic violence history, who can be awarded parenting time with appropriate conditions or restrictions under current law, will have to be branded “unfit” in order to avoid the presumption of equal time,” the letter explains. But, the letter goes on, “domestic violence encompasses emotional and mental abuse that are not “actionable criminal activity.”

Moreover, the burden of proof would be an enormous obstacle for custody cases that involve a history of domestic violence. Shiemke says, “Perhaps the most alarming aspect of the bill is the creation of multiple presumptions that apply regardless of the real-life experience of a family or the needs of a child and that can be overcome only in specific, limited circumstances. Proof to overcome the presumptions can be daunting, particularly in cases where domestic violence is present and corroborating evidence is often unavailable given the private nature of domestic abuse.”

Brown says that documenting domestic violence is difficult because much of it has not been witnessed and domestic violence behaviors are not always clear-cut or conclusive. “Many time(s) survivors are not aware that what has happened to them has a name (domestic violence). Some of those acts are non criminal acts like isolation, name -calling, shaming.” Brown says she doesn’t know how could those things could be protected against in a bill.

State Representative Jon Hoadley, who represents Michigan’s 60th District, says that this bill places an unfair burden on survivors of domestic violence. “We know that many survivors of domestic violence don’t leave the violent situation after the first incident and in fact, may cope with them in myriad of ways. But, what we’re seeing is that those lived experiences are discounted under this law if they didn’t go through a process of where they were calling police officers or had an incident report filed. And they may do that for literally incidences of survival, where the call itself may produce greater jeopardy for the family or the woman or the man or their children.”

Considering that 95 percent of custody cases never see a trial, some states are choosing to pool resources into those large majority of cases. J. Herbie DiFonzo, professor of law at Hofstra University, pointed out in an article for the Washington Post, that the focus of family law reform should be on mediation and mutually agreed upon parenting plans rather than mathematical equal parenting mandates. He points to Arizona as a example of a state that, in collaboration with mental health and child development experts, have crafted guides that parents can use as tools in helping them come to agreements on parenting plans.

It seems that all sides agree that in healthy situations, children benefit from the presence and support of each parent. Fortunately, in most cases, parents are able to come to their own agreements about what kind of shared parenting dynamic is best for their own family. When there is a conflict, though, and court intervention becomes necessary, all kids from every family dynamic benefit when their best interests are held in the center. While Michigan’s “best interests” standards may be decades old, centering the needs of kids is always timely and relevant. Representative Hoadley says, “That’s actually the purpose of a hearing and a judge, who is evaluating a case based on the best interests of the child, not some blanket regulation coming out of Lansing.”