Pressing Issues

U.S. Media Is In Crisis. Again

It's not just the truth that is under assault, but the perceptions being created by a right-wing takeover of our national and local news organizations.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Meredith Corporation has purchased Time Inc. with Koch brothers’ money. Robert Mercer personally funded Breitbart to provide a home for alt-right hate speech. The proudly conservative Sinclair Media is getting the go-ahead from the FCC to buy up multiple outlets in various local news markets. And the L.A. Weekly‘s new owners were recently unveiled as Orange County, CA conservatives. Media critics and pundits are outraged, as is liberal Twitter, where people are stunned that a handful of rich men with clear agendas are taking over American media. In fact, that horse was out of the barn a long time ago. What’s happening now is the logical end to a longstanding trend toward the consolidation of U.S. publishing into the hands of a few wealthy individuals and corporations, kicked off in 1900, when advertising became the driving financial force behind media. To find a U.S. media that’s truly independent, we need to look back more than a century in time, to the colonial and Progressive eras (1650-1900).

In the 17th and 18th centuries in America, individual journalists were printing the country’s earliest indie zines, often using sarcasm and satire to skewer the day’s politicians. It was a high-profile court case in 1735, between journalist-publisher John Peter Zenger and New York governor William Cosby that ultimately led to the specific mention of press freedom in the First Amendment. Zenger had been routinely ridiculing Crosby in his paper, New York Weekly Journal, and Crosby sued him for seditious libel. At the time, libel laws stated that the truer the statement made about someone, the harsher the punishment should be. Zenger’s lawyer, Andrew Hamilton, managed to convince the jury that the veracity of the stories about Crosby meant that he was providing a public service. They acquitted him and Hamilton went on to pen a story in Zenger’s paper arguing that newspapers should be free to criticize the government as long as what they wrote was true. Fifty-six years later that belief was codified into law as part of the First Amendment, which reads: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.”

Here again, we often have a somewhat romantic view of just how unassailable press freedom and the First Amendment are, or have ever been, in this country. Echoing Trump’s attacks on the media today, in 1798, just seven years after the ratification of the First Amendment, President John Adams passed the Sedition Act, which made it illegal for the press to criticize the government. Thomas Jefferson got rid of the law, pardoned everyone arrested under it, and reaffirmed the country’s commitment to the First Amendment upon taking office in 1801.

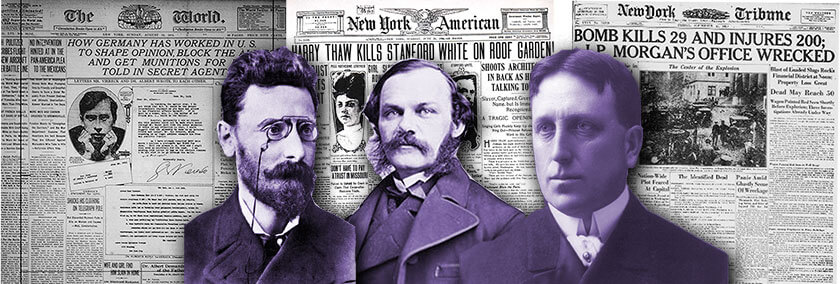

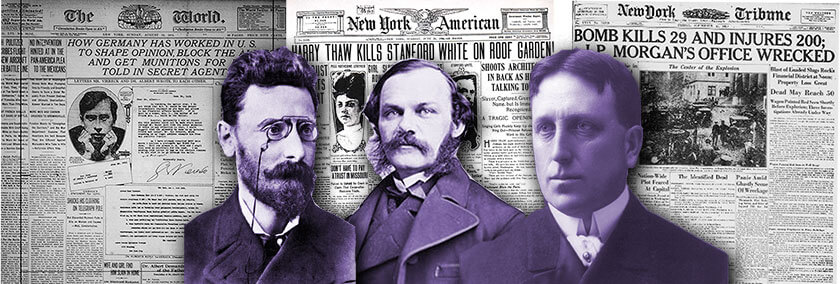

It’s worth noting that in these early days of the American newspaper, having either an opinion or an alignment with a particular party was not seen as a problem. Journalists were often adversarial toward politicians, believing it was their job to keep politicians honest and to inform the public (sounds about right, no?). Papers that aimed for neutrality tended to not sell well, which is not dissimilar to the media landscape we see today, with the likes of Breitbart and Fox News rallying some of the largest audiences and ad revenues in media. Back in the Progressive era, though, it was the left-leaning publications that crushed the competition. The New York Tribune, the nation’s first outright Progressive newspaper, launched in 1841 and went from a circulation of 10,000 to 250,000 in less than a decade. The paper took solid aim at slavery and advocated loudly for women’s rights. In his 1869 biography, Recollections of a Busy Life, Tribune founder Horace Greeley wrote, “I founded the New York Tribune as a journal removed alike from servile partisanship on the one hand and from gagged and mincing neutrality on the other.”

It wasn’t until the 1850s that papers began covering national politics heavily, and following the Civil War the idea of divorcing newspapers from political parties began to gather steam. By 1890 a quarter of American newspapers claimed to be independent of either party. It was at this time that newspapers became profitable in the country as well, thanks to a combination of reduced production costs, increased circulation, and a boom in advertising.

In the 1890s advertising began to surpass reader subscriptions as the key revenue stream for media and this is when things really began to change for the worse. Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst, the Kochs and Mercers of their time (the species has only become richer and more stratetic and conservative in the ensuing century), began to compete for circulation by printing increasingly more sensationalized articles. Big news corporations (including those owned by Hearst and Pulitzer) began to buy up independent organizations, kicking off the first big wave of American media consolidation.

Despite today’s Republican battle cry against the so-called “liberal media,” the media has in fact for more than 100 years been wildly conservative. Owned by wealthy individuals and corporations, with corporate executives and politicians as the key expert sources, the media has, as legendary media scholar Ben Bagdikian put it in The New Media Monopoly, the 2014 update to his 1983 classic, “played a central role in the culture’s shift to the right.”

“The daily printed and broadcast news on which most Americans depend has always selected as its basic sources the titled leaders of the corporate and political world,” he writes. “These sources are legitimate elements in the news since these leaders make decisions that have a major influence on the country and on the world. But in a democracy more is needed. There is another side to national realities. It is the news and views of organizations whose serious studies document the urgent needs of the middle class and the poor and of tax-supported basic institutions like public schools. … Ideas, views, and proposed programs that go beyond those of established power centers are the domain of small-circulation political journals and magazines on what, in the United States, is called ‘the Left.'”

When Bagdikian first published The Media Monopoly, in 1983, people called him an alarmist and waved away his concerns about the increasingly corporate, concentrated structure of media in the U.S. In the 30 years between that first book and his updated version, the number of corporations controlling most of America’s daily newspapers, magazines, radio and television stations, book publishers, and movie companies has dwindled from fifty to ten to five.

The problem we face today is that while the media has been fundamentally changed by money and politics, the public’s expectation of the media—that it provide a level-headed balance to public panic, that it hold up a mirror to society, that it inform the public and keep politicians honest—has not. We want journalists to perform a public service, but they work for private companies in an increasingly consolidated private enterprise. Paradoxically, the accusation of liberal bias in the media has enabled conservative thinkers to not only shift the mainstream media to the right but also create a rabid market for unapologetically partisan news, all while criticizing those that don’t share their views for being unfairly partisan.

The good and bad news is that the advertising business model is now failing as a result of the transition to digital media. This has left news organizations scrambling to redefine themselves for a new era of media and, hearteningly, many of the innovative “new” solutions hinge on the very thing that once made American newspapers truly free: relying on readers, not advertisers, for revenue.

This is the first installment of a four-part series on the state of media today. Future installments will include a look at the impact of the digital transformation, how shifting financial realities impact who gets to work in media, and where the money is today for “liberal” media.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.