From sex-positive hip-hop to visceral literature, and sketch comedy that turned our ugly cries into laughter, women creators not only offered an outlet to vent—they spoke for us.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

The traumatic gifts of 2017 were plentiful. Sexual assault victims had to revisit their memories time and again as predators dominated—and still dominate—the headlines. People of color were reminded that they are less important than Whites—even if they do save elections. Even Mother Earth, who could not be moreemotive in her plea for help, was abandoned.

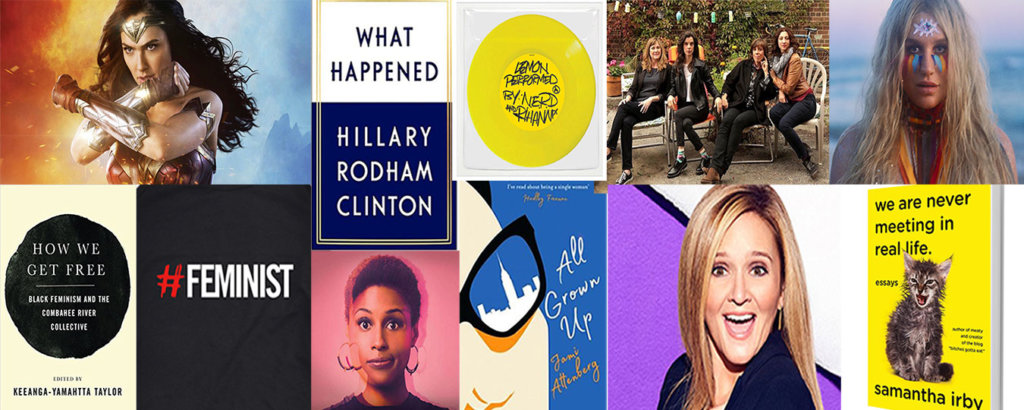

But while this year was indeed a perfect storm of terrible, it also gave us extraordinary art, without which we might not have survived. As usual, but particularly this past year, female artists were the master translators of culture. While we admit that Eminem’s anti-Trump rant, “The Storm”, spoke to us and that the message of tolerance woven into Guillermo del Toro’s supernatural drama, The Shape of Water, feels timelier than ever, these expressions served to reiterate, not reinvent, the rage women have been screaming about our entire lives, but especially since the election of Donald Trump last year. A resistance movement that began with crocheted vulva hats has evolved to include a chorus of women being vocal about injustice—from victims of harassment and assault finding their voices to female members of Congress standing up to the bullies in their ranks, to female artists speaking for those who can’t. These are the books, music, film, and television by female creators who fulfilled what we believe Maya Angelou meant as prophecy when she said, “There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you.” These storytellers got us—and might have just saved us.

Female authors have always been our saviors.

Women writers are the true documentarians and soothsayers of history. Before feminism was the word of the year, and certainly before it was a political movement, Virginia Woolf drew attention to sexist social constructs in A Room of One’s Own. When Margaret Atwood wrote The Handmaid’s Tale in 1985, did she know she’d be predicting our worst-nightmares-almost-come-true? And what was Maya Angelou’s gift if not reading our minds and forcing us to make better use of them? This year, the books by women we loved most of all—and this list does not even begin to scratch the surface—allowed us to be unapologetically flawed, a concept generally not applicable to female protagonists in popular culture.

The fiction that gave us female characters as real as a yeast infection were an antidote to the year’s barrage of false perceptions of womanhood. Elif Batuman’s The Idiot and Kirsten Roupenian’s viral short story “Cat Person,” busted stereotypes of what it means to be a young woman at a critical—and often criticized—stage in life. Jami Attenberg’s All Grown Up dared to feature a woman unfulfilled in midlife, but not particularly hankering to change things. Andrea Bern is selfish and a little bit lazy, and, no, she really doesn’t give a shit about having kids or getting married, and why do you keep asking her those same questions? Andrea would ask, “Who am I?” if the question weren’t so goddamned irritating. Andrea’s insistence to be left alone to live her life however she wants—and if it’s not going how she wants, at least she’s the one in control of it—is a dose of realism that serves as unexpected encouragement. Be authentic, no matter what form it takes.

Memoirs by Samantha Irby (We Are Never Meeting in Real Life) and Ariel Levy (The Rules Do Not Apply) gave women permission slips to talk freely about our issues, and still feel pretty good about ourselves—or not; just feeling is okay too. Few modern writers can spin pain into beautiful prose quite like Roxane Gay, whose memoir, Hunger, does the thing most women can’t bear to do. It stares directly and deeply into her body, reaches in and pulls out all of its perceived flaws, and lays them out—still raw—for us to see. This book is an emotional experience, not only because the past abuse Gay suffered is heartbreaking to witness, but because every woman alive has her own cluster of tangled roots that leads to a source of insecurity. Gay lets us in by opening herself up, and in turn, helps us feel less alone. It’s brave and somewhat unfair that she sacrifice herself like this, but it’s what the best artists do, despite the consequences.

On the other side of the looking glass is Carmen Maria Machado’s Her Body and Other Parties, which pulls us into a fantasy world without boundaries. All the short stories in this collection—which was nominated for the National Book Award before it was even released—peer into the lives of women, all of whom have suffered abuse. Each is on the verge of something–death, ecstasy, love, rage, reincarnation. The prose is written as sci-fi—or is it fairy tale?—and yet somehow each story feels modern. Machado has basically invented a new genre of literature, which is something only a woman could do.

Feminist nonfiction selections were particularly robust this year because never before has there been so much to which we simply needed to respond. Hillary Clinton’s What Happened was necessary after the abuse that our first-ever major party female presidential candidate endured. It’s sometimes hard to re-live, but there is relief in knowing that she finally gets to speak for herself. Equally critical was the anthology, Nasty Women: Feminism, Resistance, and Revolution in Trump’s America, edited by Kate Harding and Samhita Mukhopadhyay, which offered a chorus of women writers reflecting on the year that was–and everything it wasn’t. Jaclyn Friedman’s Unscrewed: Women, Sex, Power, and How to Stop Letting the System Screw Us All puts every major feminist issue (still) facing women today into the context of our digitized, Trumpified world, where the quest for celebrity has mucked everything up. Keeanga-Yamhatta Taylor’s How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective is a critical reminder of the importance of Black women activists, the mothers of everything, including the feminist movement.

The music that translated our emotions

Escaping confinement was a consistent theme in the year’s best music. Cardi B, who survived domestic violence and earned money to pay for school by working as an exotic dancer, became the most successful female hip-hop artist since Nicki Minaj by following her template of creative sovereignty. Cardi B’s breakout single, “Bodak Yellow” (which shot to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart) shuts down critical perceptions that her body, and how she uses it, is in anyone else’s purview. Debating the over-sexualization of Black women in hip-hop can be a feminist Pandora’s box, but Cardi B isn’t here to debate. She is declaring her power, her agency, and her irrefutable talent. That’s a helluva lot more powerful than a pink pussy hat.

Rihanna and N.E.R.D. would be a dream-team collaboration singing nursery rhymes. But their collaboration on the single, “Lemon,” is expressionist art custom made for 2017. The song, which features Rihanna rapping with the swagger of Tupac, gives life to the frustrations boiling up inside us all. But it’s the video that offers release. In it, dancer Mette Towley uses her body to show off the power in physical movement–it can shred fear, dissolve insecurity, and serve as an ecstatic awakening. The experience is a cleansing, which we can’t get enough of after this year.

When we needed a good cry, we turned to Aimee Mann’s Mental Illness, which somehow manages to make her always-haunting voice even more heartbreaking. The record is peppered with Mann’s signature depressing levity, such as this lyric from the track, “Patient Zero”: “Life is grand/And wouldn’t you like to have it go as planned?” St. Vincent’s MASSEDUCATION schools us on the all-too-real truths about relationships, namely that love hurts and people are disappointing. And even though Solange’s A Seat at the Table came out in 2016, its melodic therapy resonates especially well this year. This extraordinary album by the woman who will no longer be known as Beyoncé’s little sister addresses Black beauty and survival in moody, ethereal harmonies that sound like journal entries. She called it her “project on identity, empowerment, independence, grief and healing,” reminding us that in times such as these, the political is more personal than ever.

If we look specifically at the ways in which women have been mistreated, disrespected, and abused this year, the most prescient album has to be Kesha’s Rainbow. Released before the #MeToo movement took shape, this work of art is a soundtrack for survivors. Kesha has spent the past three years entangled in a nasty lawsuit against producer Dr. Luke, whom she has accused of emotionally and sexually abusing her. Rainbow is both a revenge record and a source of unlikely optimism. From the first track, “Bastards” (which is a direct-address to all bullies), to the emotional masterpiece, “Praying” (if her multi-octave crescendo culminating with “the best is yet to come” doesn’t leave you in tears, congratulations on having a much better year than most of us), Kesha is prescribing a course of action for any woman who has ever been victimized: Love yourself, reject negativity, and in forgiveness, find freedom. If Kesha, after suffering abuse, career assassination, critical health issues, and near bankruptcy can exit this year on a message of positivity–her duet with Dolly Parton, “Old Flames,” is the pick-me-up we didn’t know we needed–then there may be hope for the rest of us.

On television, funny women allowed us to laugh at our pain.

While we loved female-written comedies such as Broad City, Insecure, Chewing Gum, Better Things, SMILF, Crazy Ex-Girlfriend and The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, the women of sketch comedy ruled our world this year. Rooted in sad, painful, frustrating truths, the sketches and segments of the following shows allowed us to laugh at the worst the world threw at us.

The women of Saturday Night Live have always been the power players—from Jan Hooks and Gilda Radner repping for second-wave feminism, to Tina Fey and Amy Poehler crashing the writers’ room, to Maya Rudolph and Kristen Wiig proving that girls can do physical comedy just as well as the boys.

This year, however, the lead female cast members of SNL—Aidy Bryant, Leslie Jones, Kate McKinnon, and Cecily Strong—have managed to turn the year’s misogynist absurdity into, well, something even more absurd: Truth. There are too many sketches that caused us to laugh/cry—from Strong’s “Claire from HR,” visiting Weekend Update to give an infuriatingly unnecessary sexual harassment quiz (“there are no wrong answers, just super wrong answers”) after which she guzzles Purell; to every iteration of McKinnon as Kellyanne Conway spinning lies. But the sketch that best represents the comedy of horrors women have experienced in 2017 is the short film, “Welcome to Hell,” which will forevermore serve as our answer to male apologists, mansplainers, and maybe just men talking in our general direction.

While Lorne Michaels gives the lead female cast members of SNL a lot of creative leeway, the four hilarious 40-something Canadian women of IFC’s Baroness von Sketch shows us just how wonderfully absurd feminist comedy can go when women are running the whole damn show. Carolyn Taylor, Meredith MacNeil, Aurora Browne, and Jennifer Whalen take on sex, body image, friendship, and menopause (a thing that happens to women!) in ways we’ve never before seen, with sketches about buying Monostat from a female pharmacist with a shame fetish; a woman who clings to dry shampoo like a life raft as her marriage implodes; and an intimate wine date among four friends that goes way past the tipping point (who hasn’t been there before?). And those are just the sketches that we can describe in a few words without ruining the jokes.

If the women of SNL are our ambassadors of rage, and the Baronesses their sisters in arms, Samantha Bee is our queen. Full Frontal with Samantha Bee was one of the first to cry “fake news!” on Ivanka Trump’s faux-feminism and one of the only shows that consistently covers the growing threat to reproductive rights–and family leave, and Russia, and the alive-and-well white supremacist movement … Bee and her mostly female writing staff have influenced actual bureaucratic progress on backlogged rape kits and upstaged the White House Correspondents’ Dinner with a parody version that won an Emmy. As far as we’re concerned, Bee’s appointment as our Angry-Woman-In-Chief shall remain permanent until we no longer need to shed light on the multitude of ways women suffer injustice at work, in their relationships, in the margins of rushed legislation, when walking down the street… Sigh. Eternal monarchy it is.

Women filmmakers gave us fantasy worlds as a therapeutic escape.

Pay no attention to the Golden Globe nominations that snubbed the best directors in film. The movies that changed our lives this year were made by women (and not inconsequently, women-led films are now the top-grossing of all time). Dee Rees’s Mudbound is a film about racial tensions at the turn of the century that speaks loudly of our modern, torn society. It dares every viewer not to reflect on his or her role in sustaining racism. The Big Sick, co-written and co-produced by Emily V Gordon, tells her real-life love story with Kumail Nanjiani, and its success could have the power to rewrite the mostly White casting tradition of romantic comedies. And Lady Bird and Wonder Women, two of the biggest box-office and critical hits of the year, also gave us worlds into which we wanted to escape.

We know we’re not the only ones who have fantasized about an all-female utopia, safe from the abusive powers of the Patriarchy. Themyscira, Diana’s homeland in Wonder Woman, offered a glimpse of that dream life. Beautiful waterfalls, lush, green landscapes, female gladiators who can catch fish by hand and battle actual Gods, and a community of matriarchal nurturing and support free from infighting and one-upmanship to compete for the attention of males. And no wayward penises! We want to go to there.

While Lady Bird painted a sometimes painful portrait of that awkward/confusing time in a girl’s life just before she becomes an adult, it is also a film full of hope. Most of us have already lived through this awkward transition, and probably many more since then–graduating college, starting a career, finding and losing love, marriage, divorce, children, the death of a loved one. Lady Bird reminds us that we’re still here; that we can get through anything. It’s a reminder that life goes by in stages and phases, and we are capable of getting through each one.

There were a lot of bad days in 2017, but there are many more to look forward to in 2018 and beyond.