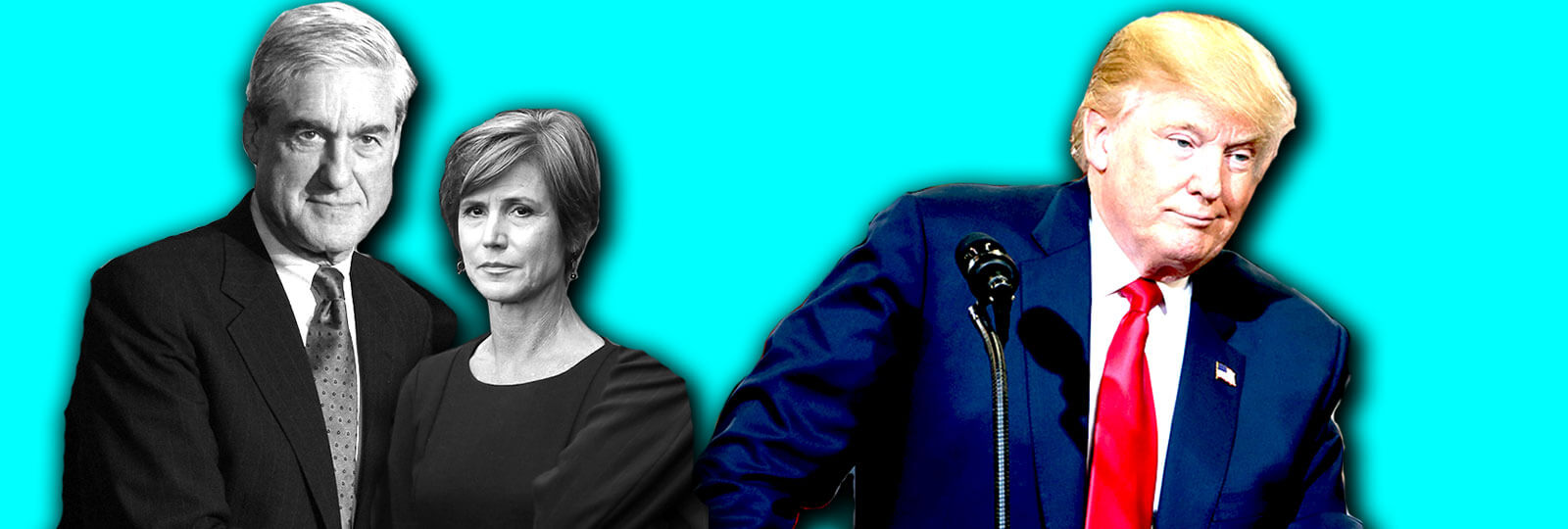

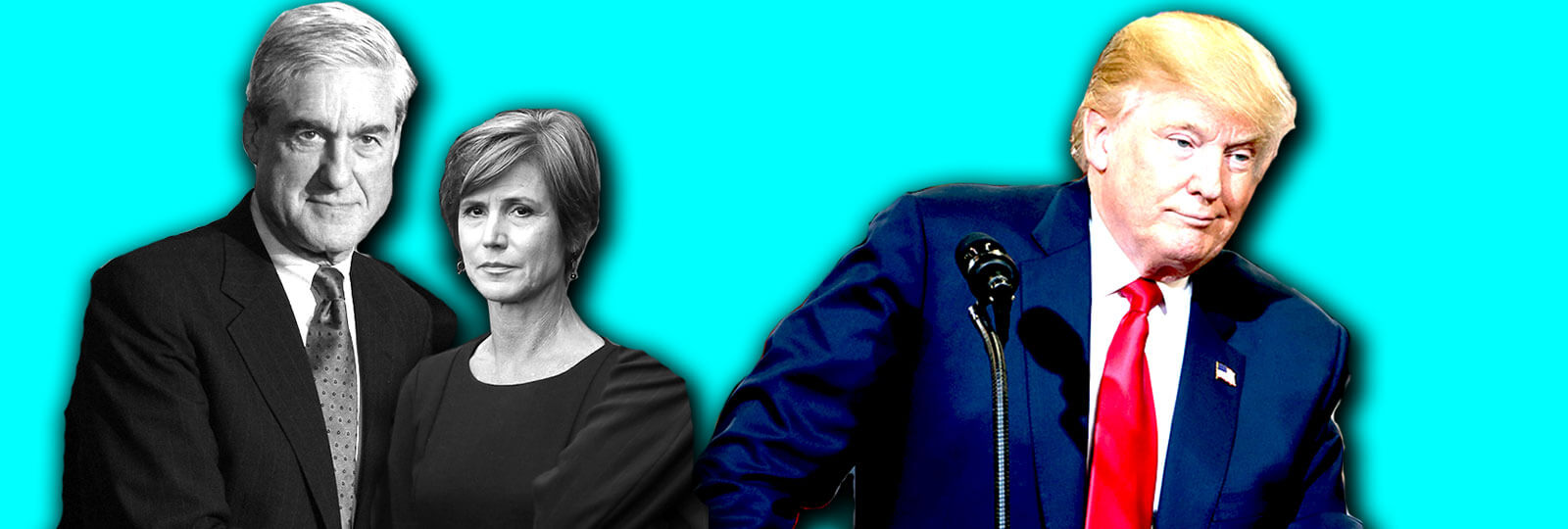

Reuters / Stoyan Nenov,Carlos Barria -Adobe, Gage Skidmore/CC2.0

Explain This

Reuters / Stoyan Nenov,Carlos Barria -Adobe, Gage Skidmore/CC2.0

Our State of the Obstruction Address

Trump has made history in his record-breaking attempts to obstructing justice. But will he actually get prosecuted?

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

One of the most terrifying things about the last year has been how quickly it seemed utterly commonplace that the President of the United States would attempt, with varying degrees of success, to obstruct justice. Sure, the articles of impeachment for Richard Nixon included an obstruction of justice component, thanks to Nixon working overtime to cover up his connection to the Watergate burglary, but that burglary occurred over three years into Nixon’s presidency. Sure, Bill Clinton got dinged with the same charge while in his second term, but it was over something equal parts pathetic and tawdry: trying to cover up his affair with Monica Lewinsky. But Donald Trump is in a class all by himself where obstruction of justice is concerned. It’s the one thing where Trump can truly say he outshines all the other presidents. Just look at the body count so far: He fired former FBI Director James Comey. He fired former Acting Attorney General Sally Yates. And, we now know that he tried to fire the special counsel, Robert Mueller. The only reason he didn’t succeed in firing Mueller was that White House Counsel Don McGahn somehow grew the tiniest sense of morality and spine and refused to carry out the order.

First, it’s useful to drill down to what obstruction of justice actually is. There are a number of federal statutes that deal with it, but it isn’t clear if any of them are an exact fit for the actions of Trump. The statutes generally refer to actions that “obstruct, influence, or impede” any official proceeding. There remain lots of questions as to what constitutes an official proceeding and what it really means to obstruct or impede, but one thing is key: In order to obstruct justice, you have to prove that someone acted with corrupt intent—in other words, that they knew what they were doing was wrong and did so with the specific goal of obstructing justice. And that’s the problem: It is awfully difficult to discern what anyone is thinking. Doubly so with Trump who doesn’t seem to do much in the way of thinking. But let’s see if we can figure out what he obstructed and when.

Let’s rewind back to January 24, 2017: That’s the day that Trump’s short-lived National Security Adviser, Michael Flynn, decided it would be a great idea to meet with the FBI without a lawyer to talk about his communications with Russia and to also keep that meeting a secret from the president and other officials. One person who did find out about that meeting, however, was former Acting Attorney General Sally Yates, who told the White House about the meeting two days later. So, six days into his presidency, Trump knows that Flynn lied to now-Vice-President Mike Pence, among others, about whether he’d talked to the Russian ambassador, Sergey Kislyak. Yates felt compelled to tell the White House about this because people that cover up their contact with Russians might be vulnerable to blackmail by the Russian government. (For her trouble, of course, Yates got fired five days later for refusing to defend Trump’s indefensible Muslim travel ban.)

The day after Yates talked to the White House, the then-head of the FBI James Comey was called to a private dinner with Trump in which he asked him to pledge his loyalty to Trump, which, you know, is a totally normal thing to ask.

Let’s break down that timeline a bit. Only one week into his presidency(!!!), Trump decides to demand loyalty from the head of the FBI, when he is already aware that Michael Flynn has talked about Russia to that very same FBI. But Trump doesn’t fire Flynn until February 13, 2017—a long time to leave a possibly-compromised person as your No. 1 national security person. Now here’s where stuff gets obviously obstruction-y for the first time: The next day, Trump meets with James Comey in the Oval Office and says “I hope you can see your way clear to letting this go, to letting Flynn go … He is a good guy. I hope you can let this go.”

Yes, the President of the United States asked the director of the FBI to stop an investigation because he thinks someone is a good guy. It’s a stretch to think Trump would stick his neck out for someone, however. He demands loyalty but rarely shows it. It is far more likely he asked Comey to back off of Flynn because he was concerned, and rightly so, that any investigation of Flynn and his Russian contacts would eventually get all the way to Trump.

About a month later, in late March 2017, Comey confirms that the FBI is looking into whether members of the Trump campaign colluded with the Russians during the 2016 election. So it comes as little surprise that Trump fires him on May 9. The comically pretextual reason for this firing that gets initially trotted out is Comey’s mishandling the Hillary Clinton email “scandal.” Of course, Trump being Trump, he literally only makes it 48 hours before he confesses that he fired Comey because of “the Russia thing.”

This path of action doesn’t work out so well, because it leads to former FBI Director Robert Mueller III being named special counsel with the authority to investigate any links between the Russian government and people associated with the Trump campaign and this delightfully broad additional authority: “any matters that arose or may arise directly from the investigation.”

Since then, we’ve seen the indictments come in for Trump’s former campaign manager Paul Manafort and campaign adviser, Rick Gates. Foreign policy adviser George Papadopoulos pleaded guilty to lying about his substantial contacts with Russia, and, of course, Flynn abandoned the sinking ship and pleaded out to save his own skin.

Here’s where obstruction on Trump’s part pops back up. A few days after Flynn pleaded guilty, Trump tweeted: “I had to fire General Flynn because he lied to the Vice President and the FBI. He has pled guilty to those lies. It is a shame because his actions during the transition were lawful. There was nothing to hide!”

Typical Trump bluster? Of course. But there’s a little more there. Trump is basically saying here that he fired Flynn because Flynn lied to the FBI. (Lying to the FBI is, of course, in and of itself a crime.) If Trump knew when he fired Flynn, that Flynn had committed a crime but nonetheless urged Comey to drop the investigation, that looks a lot like obstruction of justice: Trump attempted to stop an official proceeding. And that doesn’t even begin to address the fact that he then later fired Comey over the Russia investigation.

Trump isn’t above inducing others to impede investigations either. Look at Attorney General Jeff Sessions. In October, Jeff Sessions got grilled by the Senate Judiciary Committee about the Trump campaign’s connections to Russia. (Let’s not forget that Sessions himself lied under oath about his own contacts with Russia during the campaign.) Sessions repeatedly refused to answer questions, citing executive privilege. Executive privilege allows the president to withhold certain information about internal discussions and deliberations from the public. But here’s the thing: only the president can invoke executive privilege. Members of the executive branch, like Sessions, may invoke it on behalf of the president for only a short time—basically as long as it takes for the president himself that he wants to invoke the privilege and not have his executive branch employees answer questions from Congress. But Sessions is using it as a shield to refuse to answer indefinitely, even though Trump has never actually invoked the privilege.

Which brings us to Steve Bannon. On January 16, Bannon appeared before the House Intelligence Committee, but he spent a lot of time checking in with the White House and then presumably at the White House counsel’s direction, said he couldn’t discuss any activities related to his time in the White House or his time working on the transition team. Put another way, it appears that the White House instructed Bannon to invoke executive privilege—which Bannon did. It’s up for debate whether that would constitute obstruction of justice, but it’s also clear that invoking executive privilege to shield communications of the transition team is problematic, as Trump wasn’t president at that time. Even Republicans like Trey “Benghazi” Gowdy (R-SC) were surprised by the breadth of what Bannon and the White House sought to conceal: “His version of executive privilege is it covers the transition, the time he was at the White House and covers time forever. […] That is no one’s definition of executive privilege.” However, Bannon has now agreed to talk to Mueller’s team voluntarily in order to avoid appearing before a grand jury, so who knows what will happen.

Meanwhile, Trump is running around saying that he’d be happy to talk to Mueller: “I would love to do it, and I would like to do it as soon as possible. I would do it under oath, absolutely.” Sure, just like he was going to release his tax returns. Also, does anyone really think Trump cares if he lies under oath?

So where does all this leave us? Trump’s lawyer has floated the equal parts insane and inane argument that the president can’t obstruct justice because “he is the chief law enforcement officer under [the Constitution’s Article II] and has every right to express his view of any case.” Given that we’ve already seen two presidents dinged with obstruction of justice in their impeachment articles, this would seem to be quite the reach.

As we head into Trump’s first State of the Union address next week, it is clear that this is far, far from over. Mueller’s investigation will continue and one-time Trump allies will continue to desert that sinking ship and agree to testify, plead guilty, or both. But remember: Republicans still run the House and Senate, and they’re never going to impeach Trump, no matter how blatant his obstruction is. But if the Democrats can take back the Congress in 2018, that obstruction might be the end of Trump. Here’s hoping.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.