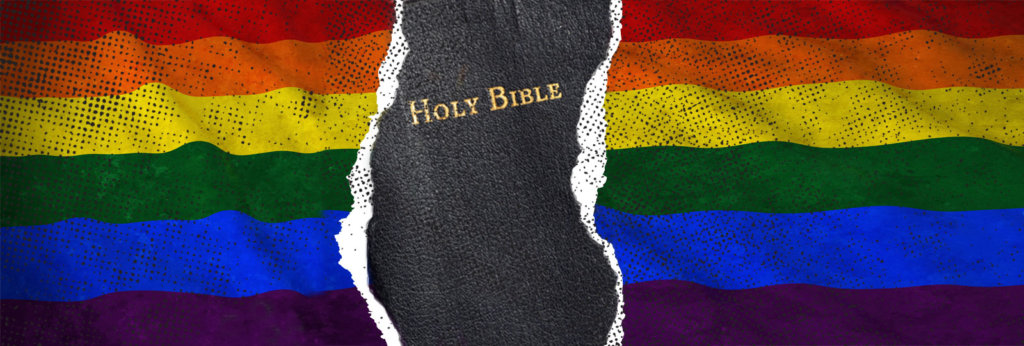

Once a predominantly violent tactic to “cure” LGBTQ people's sexuality, this "religious guidance" method has shifted more toward talk therapy. But the damaging psychological effects remain the same.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

There’s a church in Michigan offering “Unashamed Identity Workshops” geared toward teens assigned female at birth who think they may be gay, bi, or transgender to help them “be unashamed of her true sexual identity given to her by God at birth.” Critics are calling the workshops “conversion therapy,” and state legislators have since introduced a bill to ban them.

Conversion therapy rarely is outright marketed as such. In fact, Silas Musick who went through religious-based conversion therapy as part of his discipline when he was living as a woman and came out as gay at a conservative Christian University, says it is often disguised as religious guidance.

Musick, 35, now living as a trans man, says that in addition to the therapy he received at the university, he also attended Focus on the Family Institute and met with a Gender Issues analyst every week and participated in a program by Exodus International called Love Won Out. That organization has since closed its doors and apologized to the LGBTQ community for its efforts to “cure” people of homosexuality.

The pastor of Metro City Church has spoken out extensively regarding the assertion that their Unashamed Identity workshops are conversion therapy. In a YouTube video, the pastor explains:

“We think people don’t really understand what we’re doing. A lot of people are calling this ‘conversion therapy,’ and if you think conversion therapy is grabbing somebody, forcing them into some sort of pastor’s office and then beating them over the head with the Bible, and condemning them and spitting on them and judging them—that is wrong, we oppose that in every single way. What we are about is conversation, not about conversion, necessarily.”

While conversion therapy can be physically violent, sometimes involving electroshock therapy or inducing vomiting, it more commonly involves individual therapy, according to research conducted by the Williams Institute. Musick’s therapy involved things like journaling, confessing, telling “dirty thoughts” aloud and seeking forgiveness and correction. “There was a huge metaphor around the devil trying to use homosexuality to steal my soul for himself. What this ended up creating was a self-loathing that grew into a long, deep depression. Eventually, a few years after my time at Focus, I believed the world was better rid of me and I attempted suicide.”

Research published last month from the Williams Institute found that among current LGBTQ youth, 20,000 will undergo conversion therapy from a licensed health-care professional and 57,000 will undergo treatment from a religious or spiritual advisor by the time they reach 18. The American Medical Association, the American Psychological Association, and the American Academy of Pediatrics all have issued public statements opposing the use of conversion therapy because it is harmful and ineffective.

Though discredited and damaging, conversion therapy (also known as reparative or ex-gay therapy) remains legal in most states. Nine states and Washington D.C. have banned the practice, but even in those states loopholes exist that allow for religious and spiritual advisers to engage in the efforts.

Even when well-intentioned and not physically violent, the effects of internalizing messages about one’s identity as “evil” or “sinful” are damaging. Musick says, “Conversion therapy says you cannot be who you are and we will do everything to deprogram that. It strips a person of their self-dignity and self-worth. It leaves that person thinking they are a filthy part of society.”

Musick’s father is a Southern Baptist Minister in Appalachia, and having grown up with a belief system that views homosexuality as a grave sin, Musick and his parents wanted conversion therapy to work. It didn’t. Instead, Musick has spent his adult life in therapy overcoming the years of damage done by conversion therapy. “I value talk therapy. It has kept me alive. Yet, I know it can be just as dangerous as it is helpful given the wrong recipe for care,” he says.

When Seth Tooley was 13 and attending Metro City, he says that when the pastor learned Tooley was transgender, he tried to pray the “homosexuality” demon out of him. Now 17, Tooley says that the experience left him feeling terrified and unable to trust any church. “Being told that there’s a demon in you—that’s scary no matter who you are.”

The pastor of Metro City told the Detroit Free Press that he doesn’t recall the specific words they used when they prayed over Tooley, and said his church does not typically use words like, “homosexual demon.” But he said that they did pray.

Tooley says he still identifies as a Christian, but his faith has been a struggle. “I just do not like going to church and I don’t like the word ‘Christian.’ I consider myself a person who loves Christ. I just don’t like going to church, it’s too hard.”

For people who have come out as LGBTQ in the church, the trust issues and fears that Tooley describes about the church are familiar. And in today’s church marketing, brimming with “all are welcome” messages, it can be especially tricky for those in the LGBTQ community to know which churches are of the “love-the-sinner-hate-the-sin” variety and which are truly affirming.

Though Sara Cunningham was many miles away in Oklahoma City, she was one of the first to raise alarm bells about Metro City’s gender workshops. Cunningham, 55, has been fiercely advocating for LGBTQ kids—especially in a religious context—since her son came out as gay as a young adult. “I’m saying enough is enough with the shame ministry, enough is enough with the damage and devastation to our kids, to our families.”

Cunningham had been active in her church for the better part of 20 years, but when her son came out, she says that her whole family was alienated and ostracized. She has since learned that what happened to her family is not isolated, but rather part of a larger pattern of churches not being clear about their beliefs and whether they are affirming or non-affirming. “Affirming,” says Cunningham, “is where a church will celebrate the spiritual gifts of the LGBTQ person and consider same-sex marriage as holy. Anything else is non-affirming.”

Since 2015 Cunningham has been taking a Free Mom Hugs banner to Pride events, and traveling on Mother’s Day to significant LGBTQ sites. Last year they spent the day at the Stonewall Inn and this year they’re preparing to go to the Matthew Shepard memorial in Entering, Wyoming. She says there’s healing in the hugs.

“What I would have done to have seen a mother stand for what I’m standing and fighting for, what I’m fighting for for our children. What a witness that would have been to me.” Cunningham remembers how painful it was for her to absorb and then ultimately reject the idea that her son was an abomination. She says it took education and seeing other people accept her son when she didn’t know how to herself. She even wrote a book—How We Sleep At Night: A Mother’s Memoir—that details her journey from the church to the Pride Parade without losing her faith.

Musick says that so many people who undergo conversion therapy are at risk for depression and suicide, which is why he really wants parents and caregivers to understand the long-term harms that these treatments can have on their kids. While legislation to ban conversion therapy is a huge step because it would keep it out of settings where licensed professionals practice, Musick says it won’t change many of the settings where it still exists. He sees legislative bans as a way to help guide parents to more effective treatments for their youth. “Big picture, the more our society can embrace everyone of every gender, race, sexuality, ability, and class the less these practices will even be sought out.”