Skirting The Issue

Why We Need ‘Our Bodies Ourselves’ Now More Than Ever

The classic guide to sex and sexuality is going out of print at a time when women’s bodies are under attack. Will the disappearance of this resource lead to a public health crisis?

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

I’ll never forget the first time I saw a vagina—and it wasn’t my own.

I was about 10 or 11 years old, and I was hunting for buried treasure in my parents’ closet. This space was known to contain stashed-away, full-sugar candies (forbidden to me and my siblings, but I knew Dad had a sweet tooth), hidden Christmas and birthday presents, and loose change (it wasn’t stealing if I found it on the floor, I’d reasoned with my sneaky self). But this discovery—the vagina—came from a book.

Tucked away on a hidden shelf behind my mother’s expansive collection of long, flowery dresses were two books that stopped me cold. The first, The Joy of Sex, made me blush. Oh my gaawd, my preteen mind thought, grossss! The cartoonish illustrations inside of men and women contorted in weird positions didn’t change my opinion much. After two flipped pages, I rolled my eyes and put it down. But the other book piqued my curiosity: Our Bodies, Ourselves. I opened it to a random page and there it was, a black-and-white drawing of a vagina, with folds and flaps, layers and depths I didn’t even know existed. Wait, I have one of these? I thought. And it’s on the inside? I was dumbfounded. I wish I hadn’t been.

Teaching children about sex and sexuality has always been a challenge, even for the most sexually liberal parents. My mother taught my sister and me about menstruation, consent, and condoms (which at the time I thought made great water balloons). But we hadn’t yet discussed the inner workings of women’s reproductive systems, or even reproduction itself. And this wasn’t entirely her fault. By the late 1980s, there were few resources for comprehensive, science-based sexual education for adults, let alone children. Our Bodies, Ourselves (OBOS) changed that. It served as a resource for adults to learn the language of sex and sexuality, and ideally, they’d pass it along to their children. But if they didn’t, we were going to find it anyway.

Whisper networks and sneaking around, spying on our parents’ most secret things, is how kids find out about everything. By the time I hit junior high school, all of my friends had found their parents’ stash of sex books—from Our Bodies, Ourselves and The Joy of Sex to Everything You Wanted to Know About Sex and The Kama Sutra—not to mention their immense stashes of VHS porn tapes and Playboy magazines. Before these off-limits discoveries, all we had were Judy Blume and V.C. Andrews books, which taught us about menstruation and masturbation, and gave us our first soft-core introductions to sex narratives. These books were passed around from big sisters and cousins and aunts to young tweens, hidden in backpacks and discussed after school, whispered about on three-way phone calls, read and re-read until the pages wore thin. Girls were obsessed with these books because they were about the only window into sexuality that we had.

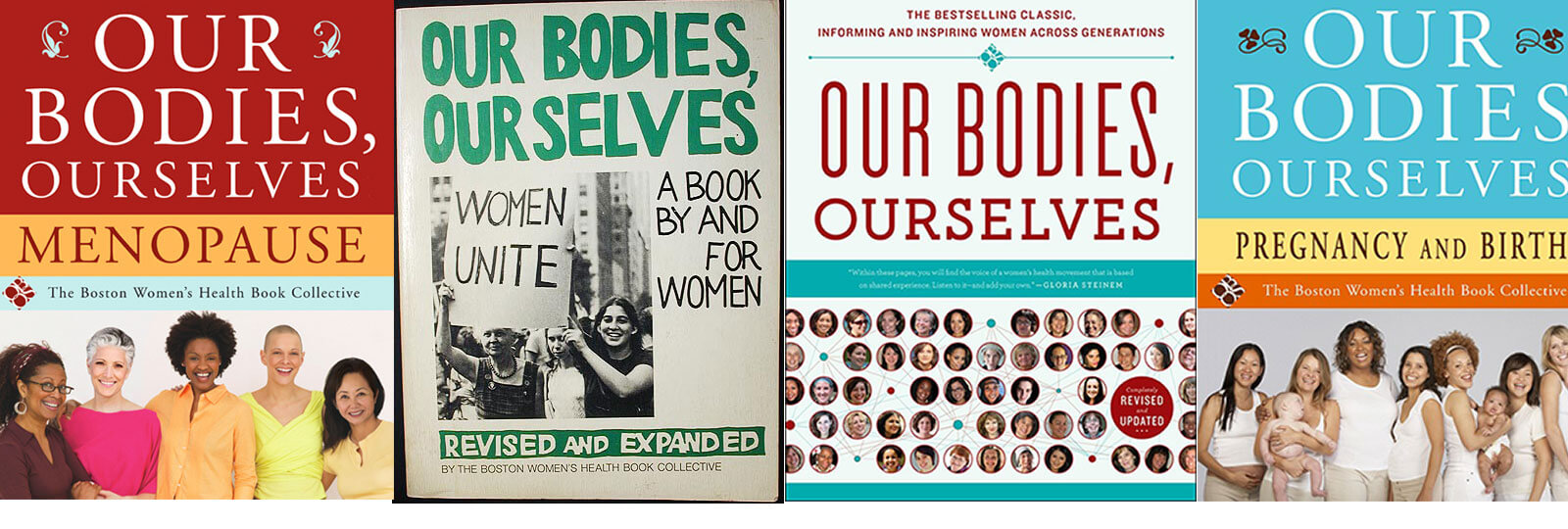

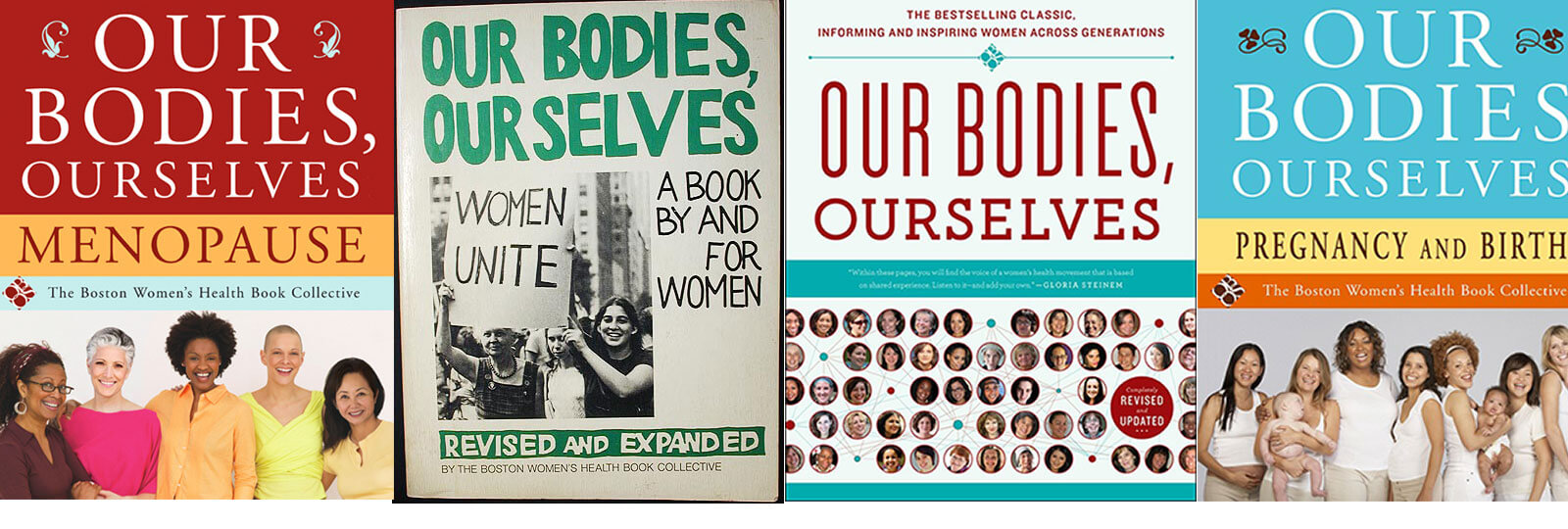

Our Bodies, Ourselves (OBOS) turned modern sexual education on its head. And after 48 years and nine editions, it will cease publication. This news, announced last week as a consequence of the small nonprofit that publishes the updates running out of money, is terrible news for sexual literacy and public health. OBOS was a revelation in practical information. The idea for the manual, which covers everything from reproductive anatomy and intercourse to social influences on sexuality and “enthusiastic consent,” sprang from a women’s liberation meeting at Emmanuel College in Boston in 1969. During the conference, a panel of doctors listened with rapt attention as the women in attendance shared their stories and questions about sex and sexuality. The doctors, all of whom were women, formed a research alliance that led to the publication of a 193-page, stapled-together pamphlet entitled, “Women and Their Bodies.” It received immediate attention—and backlash—for its frank information about women’s anatomy, the broad spectrum of sexuality, and abortion, which was illegal at the time.

A year later, the name was changed to “Our Bodies, Ourselves” to emphasize choice and women’s autonomy, and Simon & Schuster published the first commercial edition in 1973, the same year Roe v. Wade made abortion a constitutional right.

Many parents in the 1970s and 1980s had at least the benefit of participating in the sexual revolution. Central to the pursuit of gender equality (or, let’s face it, at that point merely visibility) was liberating women from the chaste constraints of sex—typically only within marriage to men—that had been previously prescribed for them. Humans, of course, have always experimented with sexuality in ways that bucked the status quo: having sex with multiple partners, same-sex partners, and experimenting with sexual pleasure. Yet sex has consistently been talked about, and depicted in ways that stigmatizes it as taboo, rather than an essential function of the human experience. Even the most “liberated” parents in the 1970s—also credited as the “Golden Age of Porn”—still couldn’t bring themselves to have practical conversations about sex with their children. And worse, they had few places to turn for help.

While biology textbooks of the 1970s were slowly beginning to include more information about sexual anatomy—such as the fact that women have reproductive organs at all—and the invention of the birth control pill forced conversations about contraception, a culture of silence and shame around sex and sexuality persisted. The federal government was slow to provide funding for sex education, leaving it up to states to decide. And when the HIV/AIDS crisis emerged in the U.S. in the early 1980s and then quickly became a pandemic, the Reagan administration’s answer was to funnel taxpayer money almost exclusively into abstinence-only education. By the end of the George W. Bush administration, Congress had spent $1.5 billion on abstinence-only-until-marriage school programs. Today, only 23 states and the District of Columbia mandate some form of sex education in schools; of that number, only 18 require that contraception information be provided. Meanwhile, 37 states require that abstinence be part of the curriculum. The Trump administration is seeking to roll back the clock 50 years or so and focus primarily on abstinence-only education (not to mention reversing the Obamacare birth control mandate, and giving states the right to defund women’s reproductive health clinics).

The message to children in abstinence-only education—or when sex education is deliberately made unavailable—is clear: Sex is bad, your body is gross, and we don’t want to talk about it!

Our Bodies, Ourselves calls bullshit on this approach, which is why we need resources like it now more than ever. Each edition of OBOS, including its final one published in 2011, opens with a direct address to women and girls: Get to know your body! The first chapter includes practical information about what female sexual reproductive organs are, how they function, and the variation in their appearance. The book encourages readers to examine their genitals with a hand mirror, which every girl on the planet should be encouraged to do considering about half of adult-aged women don’t know the difference between their vulva and vagina. OBOS also delves into the mechanics of sexual arousal—reiterating repeatedly that masturbation and orgasms are not only natural but necessary for good health. The book spells out the different types of menstrual cycles and their side effects—something tampon ads have been getting wrong forever—and how, exactly, reproduction occurs.

Adults reading this lineup of facts today may not find anything revolutionary. But ask any fourth-grader in America where babies come from and you’ll likely be met with giggles, blushing, and complete ignorance. And that’s damaging to them, and to any hope of shifting the larger cultural narrative on sex and sexuality. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends introducing fact-based sex education to children as young as 6, and according to Deborah Roffman, a teacher and author of Talk to Me First: Everything You Need to Know to Become Your Kids’ ‘Go-To’ Person About Sex, “If we’re not deliberately reaching out to kids by third grade, almost everything they learn after that is going to be remedial.”

America by and large still doesn’t talk to its young people about sex, and this silence and shame has been proven to contribute to higher rates of teen pregnancy, sexually transmitted diseases, and sexual violence, among other health risks. When countries take a practical, shame-free approach to sex-ed—like most countries in Europe, particularly The Netherlands, where sex-ed begins in kindergarten—the age of sexual activity goes up, unplanned pregnancies decrease, and young people have better overall health.

This transparency about anatomy and sexuality remains a revolutionary concept in America. There’s plenty of information these days—look no further than the Internet—but it’s nearly impossible for a child, a teenager, or even a young adult sometimes, to detect which information is accurate and science-based, and which is presented to serve an agenda. Much like Crisis Pregnancy Centers are deliberately packaged to confuse women seeking abortion services to visit their religious-backed, anti-choice clinics instead, abstinence-only rhetoric is couched in “sex-ed” speak online, in the media, and in our schools.

The messaging matters. Look at how the narrative shift during the American HIV/AIDS epidemic in the 1980s changed not only the stigma of the disease but medical research and the life expectancy of millions of people. When it became irrefutable that HIV/AIDS affected men, women, children, even the unborn, it went from being regarded by the American public “that gay disease” which was largely ignored, to a global crisis that demanded—and finally received—research dollars to study it, leading to medications that drastically extended and improved, and in many cases, saved people’s lives. But most importantly, public consciousness shifted. Safe sex became a topic on everyone’s tongue—from politicians to pop stars. Accurate, researched, true information is also the only thing that led scientists to discover the connection between Human Papillomavirus (HPV), the most common viral infection of the reproductive tract, and cervical cancer, which regularly claimed the lives of 270,000 women worldwide. But since the HPV vaccine was developed in 2006, infection rates have dropped by 90 percent.

What does all of this have to do with a book like Our Bodies, Ourselves? The stigmatizing of sex and sexuality—and women’s sexuality in particular—sustains global health crises, and accurate information is the only thing that can stop it. And given the noise of the digital- and social-media world in which we live, where those crying “fake news” are actually the perpetrators of untruths, young people need a resource removed from all of this. There are countless examples of how popular culture has let us down as a true reflection of the human condition. Female action heroes are celebrated as liberated soldiers crushing the patriarchy of the superhero genre, but there has yet to be one who doesn’t embody a glorified example of feminine sexuality, designed for the male gaze. Seemingly progressive sitcoms such as Modern Family contain jokes about men not understanding what a fallopian tube is—LOL, women’s bodies are so weird! Evocative music artists such as Beyoncé, Cardi B and Janelle Monáe receive critical acclaim for their intersectional feminist messaging in their music and videos, but inevitably are judged by the ways in which they use their female bodies.

Since the first edition of Our Bodies Ourselves, we have seen abortion and birth control legalized, only to witness access to each threatened more every single day. Members of the LGBTQ community have been given space to tell their stories and demystify much of the stigma surrounding non-cisgender heterosexual identity. Yet we have a Vice-President who preaches conversion therapy, and a president who does the bidding of homophobic conservative lobbyists by citing “religious liberty” as justification for his hateful, discriminatory executive orders to ban transgender troops, and rescind federal protection for workers discriminated against because of sex or sexual identity.

Despite our biggest gains, accurate information about sex and sexuality remains a controlled commodity. We owe it to the current and next generations of young people to give them proper media resources, allow them to discover them without shame, and to do so in private. It’s a real loss that Our Bodies, Ourselves is going out of print, but thankfully there are other trusted resources, such as the OBOS website (whose articles, often authored by doctors, mirror the book’s frank, informational tone); resource sites such as Pussypedia (a bilingual, comprehensive guide to female anatomy and sexuality), and Scarleteen (a teens-only forum that provides education and community resources in a private, confidential, shame-free setting); and an emerging group of teen-focused feminist media, such as Rookie, Teen Vogue, and Rantt, which answer questions about anal sex and sexual dysfunction under the guise of fashion and entertainment coverage, which undoubtedly boosts teens’ comfort level seeking out the content in the first place.

Normalizing curiosity about, and education of, sex and sexuality is the only way we can break the stigma that puts the population at higher risk of disease and unwanted pregnancy, contributes to social isolation and hate crimes, influences policy that claims ownership over women’s bodies, determines where research monies are allocated, and generally puts lives at risk.

The kids are going to be alright, but only if we give them access to information that might just save their lives.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.