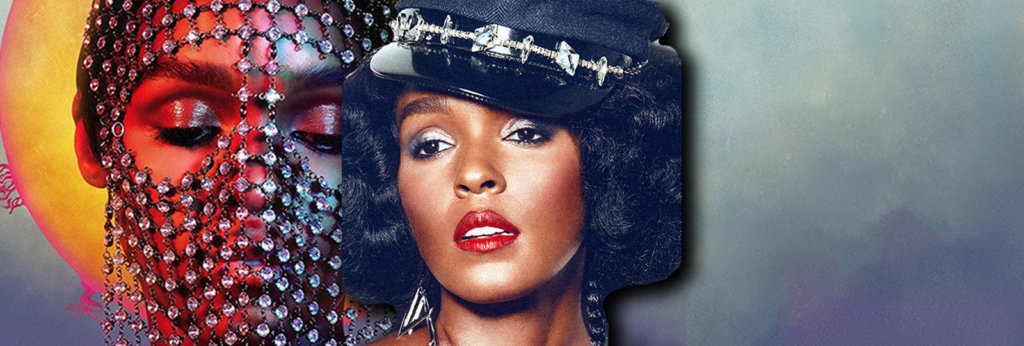

In her new visual album 'Dirty Computer,' the shape-shifting artist celebrates the core of what it means to be a woman, and finds her true identity in the process.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Janelle Monáe is finally ready to talk about herself.

In her new album, Dirty Computer, released today with an accompanying short film, which aired on BET at midnight, the artist perhaps as renowned for her ambiguous sexual identity as for her incredible original talent opens up about who she loves, and what she finds most empowering. The answer: women.

While the collaborators on this album are mostly men—with the exception of Canadian artist Grimes, there’s Brian Wilson, Pharrell Williams, Stevie Wonder, and Prince, who is not credited but was working on music with her before he died—Monáe clearly cites her female influences in each song’s liner notes, which span history, literature, film, and activist speech: Pecola Breedlove, the central character of Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye; Mary Beard’s feminist manifesto, Women & Power; Eve in the Garden of Eden; Gloria Steinem’s speeches; Naomi Wolf’s memoir, Vagina; and Dora Milaje and the women of Wakanda in Black Panther.

Dirty Computer is Monáe’s fourth solo album, coming after a span of five years. During that hiatus, her life undeniably changed. She ventured into acting and ended up starring in two Oscar-nominated films, Moonlight and Hidden Figures. She threw herself into her activism and launched the #FemTheFuture initiative to create opportunities for women to help each other succeed, a movement that would precede #TimesUp by two years. She delivered an impassioned speech and performance at the Women’s March on Washington. But just as she was beginning to work on Dirty Computer, in April 2016, her mentor and friend Prince died from an accidental overdose. The album marks an evolution of her sound, but more critically an elevated awareness of the world, and her place in it. In previous albums, Monáe filtered her messaging through a fictional character, the android Cindi Mayweather, a figure as ambiguous as herself. Now, she has become her own vessel, encouraging anyone else who has yet to use their authentic voice to do the same.

“Right now I’m escaping the gravity of the labels that people have tried to place on me that have stopped my evolution,” she told the New York Times Magazine. “You have to go ahead and soar, and not be afraid to jump—and I’m jumping right now … I knew I needed to make this album, and I put it off and put it off because the subject is Janelle Monáe.”

Truth is a scary thing for anyone, but especially an artist who has built a brand and image around ambiguity. This album is entirely about self-discovery. She claims her place as an American who is female, Black, and different than the status quo. She explores how the world sees her—and responds with a middle finger up and a wink. She celebrates her identity as a queer woman, which she has hinted at in her lyrics before, often using female pronouns for the objects of her desire. But this time, she’s shouting her truth. In the video to “PYNK,” which is itself a love letter to female sexuality, she and her all-female dancers wear ruffled pants that skirt innuendo: They are realistic recreations of the vulva—a gradient of pink tones, inner and outer labia, quivering, and full of life. In one scene, actress Tessa Thompson, Monáe’s rumored girlfriend, peeks out from between Monáe’s legs, and winks. In the video to “Make Me Feel,” the two women share a popsicle and move in for a kiss. And at the core of the short film’s narrative is a star-crossed romance between Monáe and Thompson.

Monáe has famously eluded questions about her sexuality, preferring to offer metaphorical answers like “I date androids,” but in a newly published interview in Rolling Stone, she finally says the words: “Being a queer black woman in America, someone who has been in relationships with both men and women—I consider myself to be a free-ass motherfucker.”

And with personal freedom comes sexual freedom. As she puts it in “Django Jane,” the album’s female-power anthem, “Let the vagina have a monologue.”

If Monáe is for once being her own character on this album, the vagina is her mascot, or perhaps her inner voice. Pussies are all over Dirty Computer and its accompanying videos—writhing on floors, grinding against other people, both men and women, sporting hot pants with messages like “I Grab Back,” and flirted with in lyrics such as these from the track, “Take a Byte”:

“Take a byte (just take a byte)

Help yourself (help yourself)

It’s alright (it’s alright)

I won’t tell (it feels so good when you nibble on it)”

And on “Don’t Judge Me,” taking a page right out of Prince’s playbook, she coos in a bedroom voice: “What if I, what if I touched you right there?”

Looking back at popular music over the years, and examining how vaginas have been talked about, the way that Monáe represents the beauty, power, and pleasure possibilities of the female anatomy is practically unparalleled. If they weren’t being denigrated on countless male-fronted rock and hip-hop tracks, they were being whispered about, suggested—but never named—with obscure metaphors that sent the message that vaginas should be kept secret, hidden, possessed. Even when women took control of the vagina narrative, they did it subtly. Cyndi Lauper wrote a revolutionary song about female masturbation, but had to give it a different name: “She Bop.” Christina Aguilera and Britney Spears offered up ambiguous self-pleasure songs in the 1990s while dancing for the male gaze. Madonna, who never shied away from sexual expression, was forced to censor herself, particularly when it came to what she did with her vagina in public—whether it was creating new censorship guidelines for her grinding performance at the 1984 MTV Video Music Awards, or getting sued for grabbing her crotch as part of her “Blonde Ambition” tour.

Even Beyoncé, who evolves her feminist messaging with every new song, album, or live performance, can’t quite get past the innuendo. In her most vagina-centric song yet, “Blow” from 2013’s Beyoncé, we get what she’s talking about when she sings, “Can you eat my Skittles, it’s the sweetest in the middle.” But it’s not quite the same as, “Pink, like your fingers in my… maybe. Pink, like your tongue going round… baby,” as Monáe sings in “PYNK.”

“PYNK” in particular allows Monáe to spread open her feelings about sexuality, and embrace feminine beauty, pleasure, self-pleasure, and same-sex pleasure set to a groove-pop melody. This is also the song most evocative of Prince. Not musically—that credit goes to “Make Me Feel,” which is an obvious sonic child of signature Prince synthesizing and guitar riffs—but in the way it celebrates female sexuality with respect, dignity, and outright adoration. In songs like “Soft & Wet,” “Come,” “Head,” and “Sugar Walls,” which he wrote for Sheena Easton, Prince places woman’s pleasure front and center. The narrative is romantic, never demanding or obsessive as in tail-chasing rock songs from the 1980s and beyond, nor is it pined over with heartsick desperation, as in nearly every R&B song you’ve ever heard. Prince made a point of empowering women’s sexuality through his own lens, and it’s clear Monáe, his protégé, took note.

There’s no maybe about it. Monáe’s latest expression is an unabashed ode to the vagina, which she clearly identifies as a power source for women. As Monáe is finally claiming that love and power for herself.