Dictionaries don't define words, people do. And those in power are not only eroding our lexicon, but democracy.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

There’s not much about the use of words that surprises lexicographers, which is why January 22, 2017, was so unusual. At Merriam-Webster, where I worked as a dictionary writer for 20 years, we track in real time which words people are looking up on our website as a way to see how people are engaging with the world around them, and what, in particular, is driving their curiosity about a particular news story or event. Many times, these spikes in lookups are for words people aren’t familiar with (like “cloture” or “collusion”) or for words that describe complicated or controversial topics (like “feminism” or “love”). The list of the most looked-up words ever paints an interesting picture of the ideas jostling together just beneath our cultural surface: “democracy,” “fascism,” “irony,” “bigot,” “feminism.” You get used to seeing a certain type of word on the lookup list, which is why the Merriam-Webster lexicographers boggled at the top lookup on January 22: “fact.”

Hours earlier, Kellyanne Conway and Chuck Todd had sparred on NBC’s Meet the Press over her use of the word:

CONWAY: You’re saying it [the reported size of Trump’s inauguration crowd] is a falsehood, and Sean Spicer, our press secretary is giving alternative facts to that.

TODD: Wait a minute, alternative facts? Alternative facts—four of the five facts he uttered, the one that he got right was Zeke Miller, four of the five facts he uttered are not true. Alternative facts are not facts—they’re falsehoods.

After we reported the spike, some bemoaned the state of education today: Who doesn’t know what “fact” means? The user comments on the entry for “fact” make it clear that people knew what it meant. They were looking it up to make sure that the dictionary had not scurried off to change its meaning and so cover the Trump camp’s bases lexicographically.

Most people were relieved to hear that we had done no such thing. Professionally edited dictionaries base their definitions on all the collected and contextual written uses of a word that their lexicographers can get their hands on. Lexicographers don’t decide what meaning words will have: the writing, speaking public does that whenever they use a word to mean a particular thing. It’s the lexicographer’s job instead to sift out and delineate the different meanings of a word based entirely on how other people use that word in context. In that sense, English is broadly democratic: it relies on a consensus of use and doesn’t allow one outlier to steer the force of a word’s meaning away from the rest of that word’s users. We’re not going to enter “covfefe” into the dictionary just because Trump tweeted it.

But it’s not an unfounded fear. A deliberately imprecise use of words is (and has always been, to some extent) part and parcel of politicking, and some lexicographers of the past have been willing cogs in the spin machine. English dictionaries go back to the 1600s, and until the 1800s, they were written to appease or entice a patron (usually aristocratic). Until modern times, lexicographers occasionally used their dictionaries to encourage political tensions of the day. Samuel Johnson famously threw shade at the Scottish in his 1755 definition of “oats” (“a grain, which in England is generally given to horses, but in Scotland supports the people”); in his 1828 dictionary, Noah Webster added a definition to “Americanism,” a word that referred to an American idiom or word, that had its basis in nothing but Webster’s own inflated national feeling (“The love which American citizens have to their own country, or the preference of its interests”).

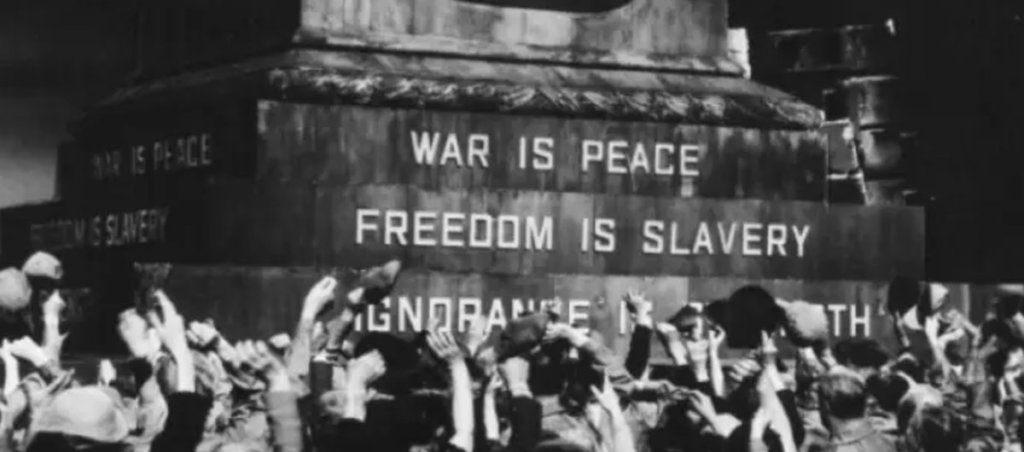

Since the rise of staff-written dictionaries, this sort of single-minded defining is rare—no one person is the dictionary. And yet current cultural (and therefore linguistic) moment seems fraught in ways that Johnson and Webster could never have imagined. We’re living in a lexicographical version of The Manchurian Candidate, where words aren’t just mishandled but have become triggers, signals, themselves a dangerous subterfuge. Facts, those things with a basis in objective reality, are not subjective? We can be forgiven, perhaps, for feeling like we’ve fallen down the rabbit-hole into a Wonderland-esque reality where our president erupts on Twitter several times a day like a logorrheic, monosyllabic Old Faithful (“Sad!” “WALL!” “WITCH HUNT!”) and he’s answered with more coded language (“FAKE NEWS!” “MAGA!”). These last few years have seen a lot of linguistic weaseling by those in power.

Take the case of “alt-right.” The word was coined by white supremacist Richard Spencer in 2008, ostensibly as an umbrella term that tries to, as Spencer puts it, “build a philosophy, an ideology around identity, European identity. To hear the Southern Poverty Law Center, which tracks hate groups, tell it, the word “alt-right” refers to “a set of far-right ideologies, groups and individuals whose core belief is that ‘white identity’ is under attack by multicultural forces using ‘political correctness’ and ‘social justice’ to undermine white people and ‘their’ civilization.” The SPLC notes that the alt-right has become home for many notable white nationalists, neo-Nazis, and white supremacists.

“Alt-right” was only brought to the national stage—lexically and literally—in 2015, when the Charleston shootings, the online boycott of Star Wars over the casting of John Boyega as the lead, and the rise of candidate Trump collided. By the time Steve Bannon, then publisher of Breitbart News, was named the chief executive of the Trump campaign in August 2016, the word “alt-right” was a mainstay of news reporting. How could it not be? Just a month prior to accepting the position with Trump’s campaign, Bannon himself had said that Breitbart was the “platform for the alt-right.”

When Trump won the election and named Bannon a chief White House strategist, the white nationalists cheered and the Associated Press put its foot down. In November 2016, the AP issued guidelines on how and when news organizations should use the term “alt-right”:

“Alt-right” (quotation marks, hyphen and lower case) may be used in quotes or modified as in the “self-described” or “so-called alt-right” in stories discussing what the movement says about itself.

Avoid using the term generically and without definition, however, because it is not well known and the term may exist primarily as a public-relations device to make its supporters’ actual beliefs less clear and more acceptable to a broader audience. In the past, we have called such beliefs racist, neo-Nazi or white supremacist.”

The article concludes, “We should not limit ourselves to letting such groups define themselves, and instead should report their actions, associations, history and positions to reveal their actual beliefs and philosophy, as well as how others see them.”

While furor over the alt-right came to a head, alt-right outlets began to distance themselves from the term “alt-right.” Breitbart claimed that it was not an alt-right publication; Lucian Wintrich, writer for the pro-Trump website The Gateway Pundit, complained that the alt-right was being co-opted by Spencer and the Nazis, and people are abandoning the term “in droves”; even the man who books Spencer’s campus appearances is identified in a Miami Herald profile as an “identitarian” since, as the publication notes, that coinage doesn’t have the connotational stink that “alt-right” does.

That doesn’t mean the word is out of circulation, or that the evidence lexicographers are collecting isn’t conflicting. In spite of the guidelines issued by the AP, “alt-right” is most often used today in print without quotation marks or modifiers. It’s also common to see “alt-right” paired with “white nationalism” or “white supremacy” as if they were distinct from one other. Just recently, after Breitbart News called Black Panther—a movie set in a fictional yet technologically superior African nation untouched by white colonization—a “pro-Trump extravaganza” which featured a hero who opposed immigration and championed a racially homogenous, ethno-nationalist state, alt-right bloggers began hollering “Black Panther Is Alt-Right!”

All this confusion has very real consequences for the lexicographer—and anyone else who uses the language. The juxtaposition of “alt-right” and “white nationalism” implies that the two are not the same (or, rather, that one is not a core tenet of the other). The labeling of a variety of ideologues as “alt-right”—men’s rights activists, eugenicists, Holocaust deniers, anti-immigration proponents, economic isolationists, anti-LGBTQ iconoclasts—makes the “big tent” of the alt-right so big that it’s no wonder that many have a hard time figuring out what, exactly, makes the alt-right “alt-right.” And that is exactly what the progenitors of the term “alt-right” want: for the term to become so blase and commonplace that no one associates it with right-wing radicalism.

Defining is an inherently political act: to say that a word means one thing and does not mean another thing is to stand for an objective reality during a time when the claim to objectivity is as subjective as it gets. It’s no surprise, then, that context, the thing lexicographers rely on during defining, is under fire by those who want to control language, and through language, reality. “What about the alt-left,” Trump groused after Charlottesville, using a word created by the alt-right in order to smear their opponents with the same extremist taint that the word “alt-right” had been (rightly) given in the press. Though “alt-left” had no use apart from alt-right forums, it was the evil twin that “alt-right” needed. It was a calculated coinage shoved into the national consciousness by Trump, a word that encouraged false equivalencies, a breakdown in conversation, and the erosion of cultural literacy. It’s not “just words, folks” as Trump himself famously claimed. It’s a sly attempt at revision. To a certain group of people in America, “fact” can now refer to a deeply held opinion not based in objective reality; news we disagree with is “fake”; people protesting white nationalism must be the dangerous “alt-left.”

Language relies entirely on context. If linguistic context is being warped for political ends, and the vox populi is silent, then we have gone through the Looking-Glass:

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.”

“The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

“The question is,” said Humpty Dumpty, “which is to be master—that’s all.”

This is the second installment in our ongoing series on America’s “shifting language.” In our first piece, we look at the media’s role in the destruction of words.