The criminal justice system continues to allow police to murder people of color and fails to compensate families for their immense loss. It is now up to us to save ourselves.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

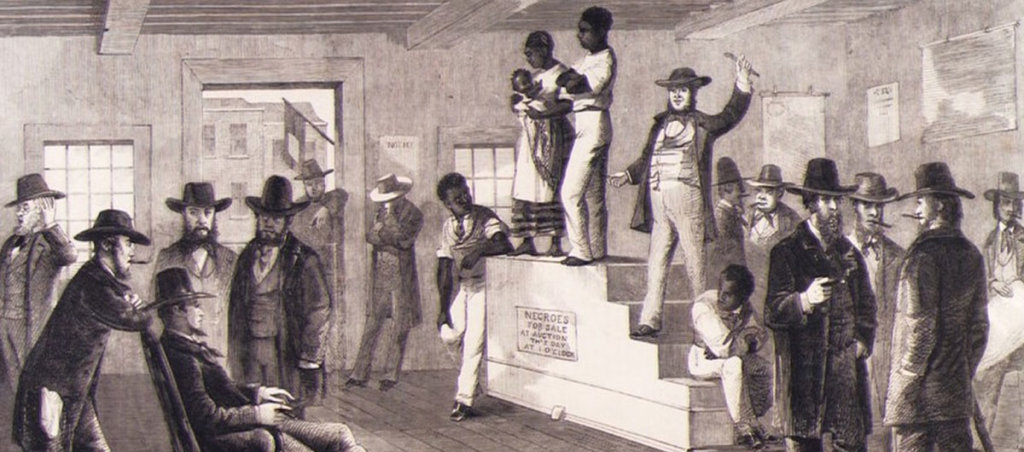

Every day I pore over my social media feed, reveling in a buffet of inspiring memes, hallmark quotes, and hashtags that reinforce the incredible magic of being Black. But as we are continually and painfully reminded with too many news stories, that appreciation does not always translate in the real world. In fact, it depreciates, a fact we’ve come to know and internalize since the 16th century, when the first African body was traded for petty goods on the Ivory Coast and pressed its footprint into American soil, where that body would be appraised, branded, monetized, and further commodified. The process is the old colonial way, and it has never quite died out, but rather shifted stylistically. Today, in lieu of debasing Blacks on auction blocks, in advertisements, and through a brutal system of chattel slavery, Black people are now devalued by police brutality and a flawed court system that facilitates state-sanctioned violence and Black appraisement. And while countless social-justice warriors have worked tirelessly to subvert this narrative, our justice system continues the appraisal and dismissal of Black bodies,153 years after slavery.

The family of Gregory Vaughn Hill Jr., a 30-year-old father of three who was gunned down by the St. Lucie County Sheriff’s deputies at his home in Fort Pierce, Florida, was awarded $4.04 for loss and damages in a wrongful death lawsuit. The decision is far more egregious than it reads when you consider several factors: 1) The federal jury did not find any wrongdoing in the officers’ use of excessive force. 2) Jurors found Christopher Newman, the deputy who killed Hill, only 1 percent negligent in the case, while faulting Hill for his own death. 3) The funds are to be divvied up among his children, minus $1 to go to his funeral services.

According to “Measuring Slavery in 2016 Dollars,” Samuel H. Williams and Northwestern University professor Lewis P. Cain state the average cost of a slave in 1860 was $400. In today’s money, that number would be equivalent to $12,000. If the same model is used to guestimate the value this jury placed on Hill’s life, we would realize just how deeply brazen and dehumanizing the verdict is. At $4 today, Hill would not be worth one dime and a nickel during slavery—and at that rate, his fate would be the same because an inestimable slave in 1860 was certainly a dead slave in 1860.

Considering this nation’s well-established history of policing, and extinguishing Black people, it is not far-fetched to assume the two deputies similarly undervalued Hill’s life, on that fateful afternoon in January 2014, when they converged at his door—and then his garage—responding to a complaint of loud music. Reportedly, Hill who was concerned about the cacophony outside his home, raised the garage door with a gun at his side, and allegedly pointed at the officers as they ordered him to drop it. Ignoring police command, Hill lowered the garage door and was executed 120 seconds later. Officer Newman fired through the garage door, striking Hill twice in his abdomen and once in the brain because he felt threatened. Hill’s 10-year-old daughter witnessed it all from her school which was across the street from her home. The gun in question was found without bullets and tucked away in the dead man’s back pocket.

Attorney John Michael Phillips is no stranger to legalities tied to lynching and loud music. In 2014, he represented the family of Jordan Davis in a wrongful-death and defamation lawsuit against Michael David Dunn. While at a Jacksonville gas station, Dunn fired ten shots into a vehicle containing three Black teenagers, and killed 17-year-old Davis in cold blood, after a verbal exchange about the volume of music the boys were listening to at the time. By Dunn’s account, he felt threatened by the boys and also the need to defend himself—though he himself was the instigator. Dunn’s initial trial ended in a mistrial, but in a retrial, Dunn was found guilty of all charges against him. Phillips negotiated a settlement for the Davis family for an undisclosed amount. Yet, he was not able to secure the same results for the Hill family.

“This verdict stung,” Phillips said during our lengthy conversation. “It’s the insult within the loss, the #BlackLivesMatter question within the loss, that trumps the loss itself.”

Phillips sought up to $10 million for the Hills, which would have worked out to $2 million per child. Hill’s $11,000 funeral expenses were included and there was no counter evidence against the children’s pain and suffering. Since economic damages were not a factor in the suit, the award amount is left to the jurors’ discretion. Because Newman was found minimally responsible for Hill’s death, his portion of compensation amounted to four cents. What should have been an open-and-shut case in the Hill family’s favor turned out to be a public Black taunt.

Awarding the Hill family $4.04 for their pain, suffering, and loss is an affront to Hill’s humanity and the Black body, and a smack in the face to Hill’s children. The message it sends to them can be heard loud and clear.

“What was on the line was the full value of the funeral expenses and their pain and suffering,” Phillips said. “It leads me to three conclusions: One, this jury was utterly confused and just got it all wrong, which I don’t see. Two, they wanted to punish this family for the Blue Lives Matter–type mentality, or three, they really believe these children are worth a dollar.”

Kiese Laymon, professor of English at the University of Mississippi and acclaimed author of How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America, has a similar take on the jury’s decision. “Our justice system, possibly more than any system in this country, does the bidding of its people. The majority of folks in this country want Black folk to have even less than we have,” Laymon tells me. “They want us to suffer more and the justice system usually reinforces this desire for more suffering.”

Both Davis’s and Hill’s deadly encounters originate from the same vein—not so much the disapproval of a Black man’s right to enjoy music at high decibels in the comfort of their own space as a refusal of white people to recognize these men as valuable beings; when blackness isn’t yielding so easily to white demands, white rage explodes at the notion that they’re losing control. Recall Dunn’s response when three Black boys rebuffed his demand “You’re not gonna talk to me like that!,” he reportedly yelled before drawing his gun down on the teenagers. In Newman’s case, Hill challenged his authority by shutting the garage door in the officers’ faces so he could return to enjoying his music—in his house. So Newman pumped bullets into the family’s home.

Instead of checking their privilege and rage, they did this, under the guise of feeling “threatened” and superior to a darker race.

The denigration of Black life is a recurring theme since the birth of this nation. As times changed, the brutal deaths of rebellious slaves at the hands of slaveholders and overseers were reenacted in public mob-lynchings of African Americans; as in the case of Zachariah Walker, who in 1911, stood his ground in a fight with a white security officer; and Laura Nelson and Mary Turner, two black women lynched for challenging racial violence against their loved ones. White inferiority is also responsible for diminishing Blackness as seen in cases where groups of Blacks were targeted and murdered by rouge racist citizens in race riots suchlike those that occurred in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Rosewood, Florida; and the mass killings carried out at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama—and more recently Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina.

The stark difference between the Davis and Hill case is Davis’s assailant was brought to justice; Hill’s murderer is among those allowed to kill with impunity. The U.S. court system has a huge impact on why this persists. Since 2005, out of thousands of police killings only 54 have been prosecuted. Of that total, almost half have been exonerated in some way. Officers facing charges need only prove reasonable force. Newman’s “threat” defense absolved him of shooting into a closed door, which happens to be a law enforcement violation. Answering your own door with a gun is not.

Bowling Green State University criminologist Philip Stinson told the Washington Post, “To charge an officer in a fatal shooting, it takes something so egregious, so over the top that it cannot be explained in any rational way.” Stinson adds, “It also has to be a case that prosecutors are willing to hang their reputation on.”

Jurors contribute to the unwillingness to convict cops who have murdered Black men and women. They are an integral part of a legal system that degrades Black people, charged with qualifying and quantifying Black bodies as we’ve seen in the cases of Hill, Philando Castile, Miriam Carey, Alton Sterling, Alberta Spruil, Eric Garner, Korryn Gaines, Freddie Grey, Tamir Rice, Sean Bell, Amadou Diallo, and too many others to name. Numbers for convicting cops remains abysmally low and remains unchecked because jurors, who are disproportionately white, tend to trust cops and devalue Blacks—and most victims in these instances are Black and the killing officers are white.

The jury for Hill’s lawsuit was made up of five white women, two white men, and one older Black man, who attorney Phillips says was “one of those old school guys who stood in stern judgement [of young men like Hill].” The composition is telling of statistical data and historical fact. That they deemed Hill’s black skin, black breath, and black lifestyle dime-store commodity is shocking, but no real surprise given this country’s racialized past.

The conversation with Laymon reveals all hope isn’t totally lost, at least not among the Black village, as when he tells me, “I don’t want to undervalue the fight of Black freedom fighters who came before us. They battled so our lives would be worth more, and what we like to call ‘backlash’ is really white folks often pushing back against this organized effort at value,” Laymon affirmed. “So I think Black lives are worth more today because all Black lives are more valued within our own communities. Queer Black lives, femme Black lives, trans Black lives, the Black lives of children are valued more today, I think, because of the work of Black folk. I want to thank the justice-oriented judges and lawyers and juries fighting for us. It is endless work.”

The context of Hill’s case reads like a new entry for an American history text, explicitly a chapter documenting police brutality of Black people that we could title “Black Lives and Lynch Laws of the 21st Century.” Police violence and the legal assessment of Blacks are reminiscent of America’s slave narrative—slave schedules and slave codes. It reeks of Jim Crow, public castration, and lynching. It’s rancid, and yet it smells as American as ever.

At this rate, Black Americans can either penetrate the judiciary process even harder than the ancestors whose shoulders we rest upon, by becoming a part of its circuit as judges, lawyers, and lawmakers, and effecting change by way of votes, participating in jury duty and jury selection. Continue to fight for us—or be prepared to kiss our Black asses good-bye.