The new AMC series imagines a world in which the patriarchy is flipped upside down, then dropped from the sky. It's fun and feels good. But whether it's justice is subject for debate.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

Who hasn’t wanted to push Terry Richardson from a plane? The famous fashion and celebrity photographer who brought the cheap aesthetics of pornography into the glamorous halls of Vogue and W Magazine was long whispered about as a sexual predator, until whispers became shouts and multiple accusations of harassment, coercion, and force became public. It’s clear that for years this man was coddled, protected, and enabled by an entire industry and many women suffered as a result.

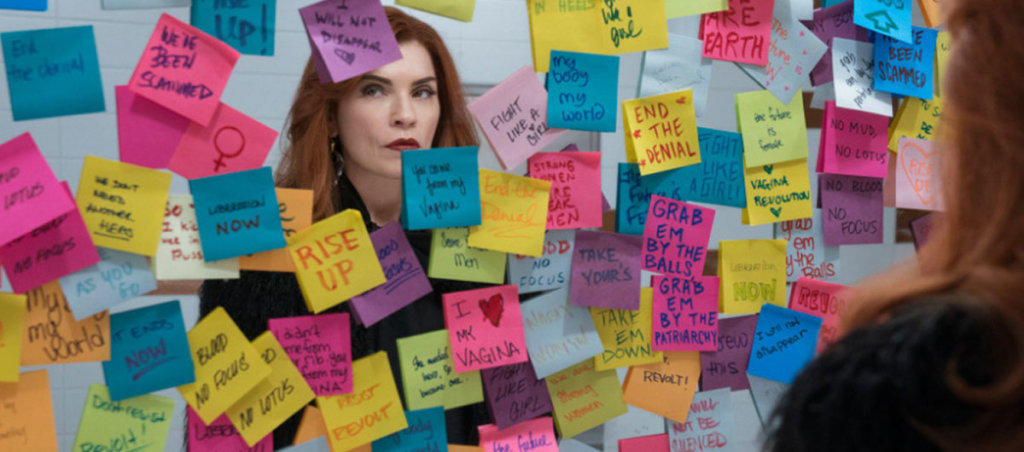

In the new AMC show Dietland, a photographer who looks remarkably like Richardson is abducted, forced to record a full confession of his misdeeds, and is pushed out of a plane. The pervy photographer is not the only one targeted. Men accused of rape and professional athletes accused of domestic abuse and sexual assault are also dropped from the sky. A man whose sin is merely publishing soft-core pictures of half-dressed women in a British tabloid is scalped and his young son is abducted. These are the acts of a radical feminist group called Jennifer, and while there is a mealy-mouthed debate on the show about whether violence is ever justifiable, it’s clear these acts are supposed to bring catharsis to its mostly female audience. “One man’s terrorist is another woman’s liberator,” says the female editor-in-chief of a successful women’s magazine.

Fantasies do not emerge wholly original from the void—they take their inspiration from real life. The methods of Jennifer—bodies dropped from planes, children abducted to force the hand of their distressed parents—come straight from the Argentinian Dirty War. There, tens of thousands of dissidents were disappeared, many of them killed in the exact same way as on Dietland: drugged, bound, and dropped out of a plane from great heights. The main character on the show, Plum, explains how the actions of Jennifer have been helping the self-esteem of teenage girls. It makes them feel “exhilarated and empowered.” As, I’m sure, the death flights made the military junta terrorizing Argentina feel exhilarated and empowered.

Because this is about power. When Jennifer issues a manifesto and threatens more violence if it is not printed across the media (a fantasy that comes from serial killers like the Zodiac Killer sending letters to newspapers), their demands are not about societal reformation, nor are they about finding a way to talk about and adjudicate violence against women. The demands are all about money and power. They want only female politicians, and they want women to be paid more than men. They like the power imbalance that is inherent in our contemporary society. They want to keep that imbalance, they just want it flipped so that women are the powerful and men are the powerless.

Revenge fantasies are harmless and cathartic, and for the most part, the reviews for Dietland have been rapturous. The Village Voice called it the “fantasy I never knew I always needed.” Many essays have been written by women who identify strongly with Plum, a self-described “fat” woman who constantly diets and struggles with self-worth. Revenge fantasies are fine if they are met with a real-world struggle for justice. But that is what our culture needs so much and is lacking.

#MeToo could have been a moment for justice, but it has consistently failed on that score. Accusations are made often without being backed up by investigation, consequences are dealt out arbitrarily, and feminists have not done nearly enough to expand the movement into fields that are not populated by women of means and power like Hollywood and media. Time’s Up, a legal defense fund associated mostly with very rich and white women celebrities that were designed to fight workplace harassment, made a big deal about funding a lawsuit against mega-chain Wal-Mart, one of the most powerful and destructive corporations in American society. But the case turns out to be not a potentially world-changing class-action but the lawsuit of one woman making complaints about one male boss. The organization has collected millions of dollars and hundreds of requests for assistance, but their actions so far have been limited to publicity stunts and a few token lawsuits.

The problem with justice is that it removes the possibility of revenge, and revenge is very popular right now. Before accusations against Junot Díaz—a powerful, award-winning writer who has been coddled, protected, and enabled by the publishing industry for years—started to surface, people were trying to get him removed from his places of employment. Díaz has long been whispered about as a predator, but when the whispers turned to shouts, all the accusations added up to were one forced kiss, some shitty and manipulative boyfriend behavior, and a nonsensical claim of “verbal sexual assault” because he said the word “rape” to a woman in a raised voice during a conversation about rape. When Boston Review, which employs Díaz as a fiction editor, investigated the claims against Díaz and decided there was nothing there that warranted removing him from his position, social and online media exploded. Three editors quit in protest. MIT, Díaz’s other employer, also recently concluded an investigation into potential misconduct and decided to retainDíaz on their faculty

There have been mumblings that not all the accusations about Díaz are out in the open yet, but to use secret and private accusations as an excuse to prevent someone from being able to make a living is not justice. That is revenge. So is forcing someone out of a job for a forced kiss. Which is why #MeToo has such potential to be destructive, and why it has ignored and attacked repeated calls by various figures like Laura Kipnis, Judith Levine, Kim Samuel, and others to arbitrate accusations before consequences are doled out, to focus on rehabilitation over punishment, or to create a kind of Truth and Reconciliation–based system that can negotiate between men and women.

Like on Dietland, it’s easier and more satisfying to imagine women committing atrocities and war crimes than to imagine a world where violence is not endemic, where romance is uncoupled from domination, and where no one demographic or person holds undue power over another. Ultimately, most women will prefer revenge over justice because revenge allows for the possibility of women gaining power and dominion over others, and to avoid becoming a victim in the future by becoming the victimizer.

For centuries, we have had models in literature and art for understanding this desire for revenge. In The Eumenides, Aeschylus portrayed the shift from bloodlust and revenge to justice through the story of Orestes. A family was being torn apart by the need to avenge one murder with another, until the whole family was threatened with annihilation and Athena, the goddess of wisdom, decided to step in. The Furies allowed for blood to be met with blood, which allowed a woman to kill her husband for killing her daughter and then a daughter and son killing their mother to avenge their father’s death, and so on. Athena recognized the insanity of this and halted the never-ending series of killings by essentially creating the jury-based court system. No longer would the personally wronged be allowed to decide what is appropriate punishment. Arbiters who are able to see the situation with a cool reason would stand between victim and wrong-doer and decide what is a fair response.

If society progresses past this point of predation and power imbalance and harm, it will only be because we actively choose wisdom over anger and justice over revenge. Otherwise real change will elude us, and next time it will be a woman in power creating violence and chaos for those under her rather than a man. That is not an Athenic victory, but merely a fashionable change.