LGBTQ

Why Is Gay Conversion Therapy Still Legal?

A survivor of the pseudoscientific treatment in the '70s says it has only become more insidious today, with devastating consequences. And it shows no sign of going away with VP Mike Pence and SCOTUS pick Brett Kavanaugh as proponents.

This article was made possible because of the generous support of DAME members. We urgently need your help to keep publishing. Will you contribute just $5 a month to support our journalism?

When I was 16, in the 1970s, I was expelled from my all-girls high school for being a lesbian. My grandmother, mother, and sister had all attended and been graduated from the same school, so my being expelled was viewed as an ugly blot on the family legacy.

Two weeks later, my Ivy League– and Seven Sisters–educated socialist civil-rights worker parents (which is to say, smart, educated, socially aware) had checked me into a nearby mental hospital with a youth division that specialized in “conversion therapy.”

Conversion therapy, also known as reparative therapy, is harmful because it attempts to alter a person’s most basic self-identification in ways that are threatening to that person’s physical and mental well-being. It is the pseudo-scientific practice of using psychological, emotional, spiritual, medical and even surgical treatments singly or in combination to attempt to change a person’s sexual orientation or gender identity.

I was at the mental hospital for several weeks being treated medically with drugs, talk therapy, aversion techniques, and behavioral modification—literal torture—to “de-gay” me. None of it made me heterosexual. But all of it made me physically ill and emotionally shattered, leaving me with psychological scars.

My experience should be merely a disturbing footnote from our recent past about how lesbians and gays were once treated with a Freudian theory since debunked along with penis envy and the Oedipal complex.

But it isn’t.

When the ex-gay movement gained traction in the 1980s and ’90s with groups like Exodus International, I became a frequent guest on national and local TV and radio talk shows as a strong opponent of the practice.

Exodus International finally came to an end, when president Alan Chambers closed the organization after 37 years, in 2013. Religious leaders were upset with the decision, saying it was giving in to immorality and changing mores that were antithetical to Christian teachings. Chambers was gay, but credited his own techniques with “de-gaying” himself, which he detailed in his memoir, Leaving Homosexuality: A Practical Guide for Men and Women Looking for a Way Out. Chambers married a woman, with whom he has two children.

Longtime chairman of the board of Exodus International, John Paulk, a self-declared former gay man and his wife, Ann, a former lesbian, were the public faces of Exodus for over a decade. I appeared with them on TV and they were featured on the August 1998 cover of Newsweek. But in a 2014 column for Politico, Paulk recounted his history as a purveyor of the ex-gay cure for Exodus, the book he co-authored with his wife, Love Won Out: How God’s Love Helped 2 People Leave Homosexuality and Find Each Other, the three kids they had together, and his realization that … he is still gay.

Ann Paulk has continued to promote conversion therapy. She founded Restored Hope Network, an interdenominational Christian ex-gay ministry run primarily by former Exodus International leaders—she remains its executive director.

The Paulks are the link between the anti-LGBTQ Family Research Council (FRC) and Exodus, working for both groups. FRC, like Exodus, includes many licensed psychologists and mental health counselors and uses pseudo-scientific studies of the dangers of homosexuality to promote its quest for anti-LGBTQ legislation—as well as conversion therapy. The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) lists FRC as a hate group. SPLC previously cited Exodus International and another organization, JONAH (Jews Offering New Alternatives to Homosexuality), as hate groups as well. That Exodus International was able to operate and continue to influence thousands with its 250 groups worldwide until a mere five years ago is shocking.

Also shocking: Conversion therapy is only banned for minors (17 and under) in 13 states and legal for adults (18 and older) in all 50 states. A law banning conversion therapy for adults is pending in California. If AB 2943 is passed, California would become the first state to completely ban the practice for both minors and adults.

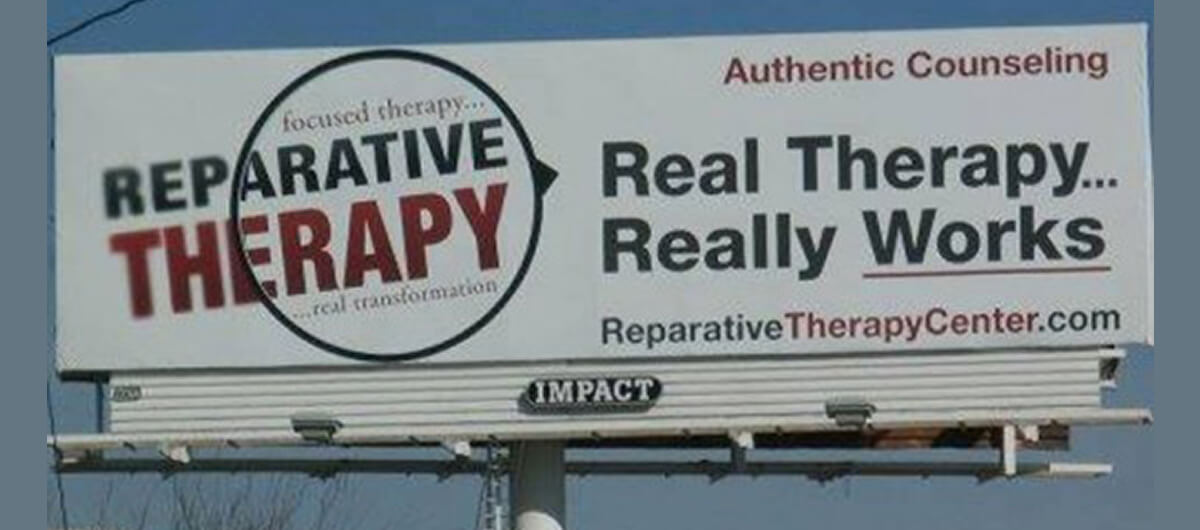

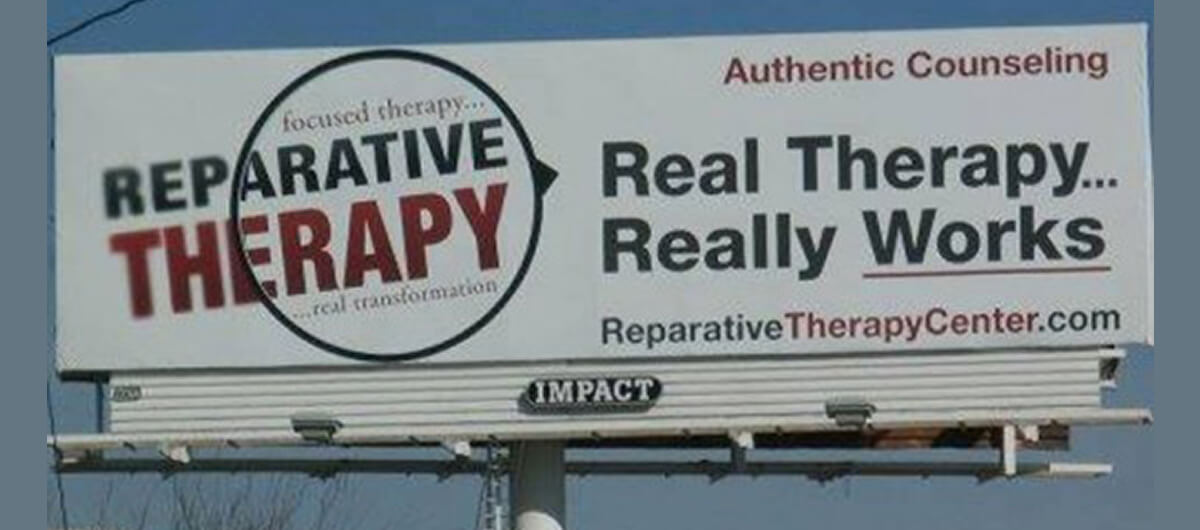

The bans are also very narrow. They only cover licensed psychologists, psychiatrists, and other licensed counselors. Those counselors are legally allowed to refer their patients—or their patients’ parents—to other professionals specializing in conversion therapy, but outside the scope of mental health care. A quick Google search for people specializing in conversion therapy provides pages of options, some prominently displayed at the top of the first search page. If you want conversion therapy, you can obtain it easily. If parents want their child to have it, they can force it on that minor with no repercussions. Some of the people who worked for Exodus International have continued reparative therapy programs under different names. Chambers himself founded a new group, Reduce Fear.

In 2015, JONAH was forced to close after nearly 20 years by court order after losing the first-ever class action lawsuit against a group offering conversion therapy. A group of gay men who had undergone conversion therapy as teenagers sued the non-profit organization because they had not been turned heterosexual as promised by the founder, psychotherapist Arthur Goldberg.

The JONAH lawsuit pivoted on the issues raised by the California bill: Is conversion therapy, on its face, a deceptive practice? The judge in the JONAH case said yes, “the theory that homosexuality is a disorder is not novel but—like the notion that the earth is flat and the sun revolves around it—instead is outdated and refuted.”

The California bill is groundbreaking in that it changes the circumstances for banning conversion therapy from mental health care to business practices. The bill stipulates that conversion therapy is harmful under all conditions—even an adult knowingly choosing it—and that the resulting outcomes can cause too much harm to allow it. Ever. The pending bill could be the one that takes conversion therapy to the U.S. Supreme Court without Justice Anthony Kennedy, who has protected, affirmed, and made history regarding LGBTQ rights in several landmark cases from ending sodomy laws against lesbians and gay men in Lawrence v. Texas to the landmark ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015, which legalized same-sex marriage.

The techniques being used at the mental hospital where I was treated included anti-depressant and anti-psychotic medications, talk therapy, and aversion therapy. I was given medications that caused me to vomit while a therapist had me to watch video compilations of photographs of naked women or women engaging in mild sexual contact—kissing and breast fondling—or other romantic or sexual situations. The technique is supposed to make the person associate same-sex acts and desires with literal revulsion. You sit with an emesis basin in your lap while a series of images flash onscreen. The medication lasts for hours, and the images of the women stay in your mind, so the connection is supposed to be lasting. Though I was not subjected to electroshock therapy (ECT), it was a common practice—there were other teens in my group who underwent the treatment. The results were harrowing, producing teens that seemed vacant and distant from their surroundings and other people.

My personal experience of conversion therapy was so psychologically and emotionally disruptive, that I attempted suicide not long after being released from the hospital.

Though, I survived, many others do not, like Leelah Alcorn. In 2014, Alcorn, a 17-year-old trans teen, committed suicide after her parents forced her to undergo conversion therapy. Her death outraged trans activists and opponents of conversion therapy and rallied new attention to the practice—though of course it still exists.

Grace McCabe* (not her real name) was a rising sophomore at a prestigious New England college in 1989 when her parents put her in a mental hospital for conversion therapy over summer vacation. McCabe had fallen in love with another female student her freshman year and, when it ended badly, she had come home deeply depressed. “Andrea and I had this really intense thing for months and then she just dumped me after spring break,” McCabe recalls. “For a guy. Not for another girl, but for a guy!” McCabe was gutted. “I couldn’t breathe thinking about her. This was my first real lesbian relationship. It was uncharted territory. I thought we were on the same page and then Andrea told me that she just couldn’t see herself with other women ‘long term.’ I’d had crushes on girls in high school, but it wasn’t until I was away from home and involved in all these feminist activities on campus where there were out lesbians that I felt I could step into that world and see if it fit. I was so in love with Andrea that I just knew that was it—I was a lesbian.”

But McCabe says when Andrea left her, she began to question her own sexual orientation. “If Andrea could be so lesbian one minute with me, then straight the next with him, maybe that could be—or would be—true for me, too. Maybe I should revisit the whole idea that I was a lesbian.”

McCabe’s parents didn’t know why McCabe was depressed, and they were worried. They suggested therapy. After several visits, the therapist recommended conversion therapy to the family as a solution to McCabe’s depression, which she believed was caused by McCabe’s “confused sexual choices.”

“My parents and the therapist had a session together,” McCabe recalls. “She said because I was still so young—I had just turned 19 a week after I came home from school—I could ‘reset’ my sexuality. It honestly all seemed to make sense at the time because I was young, my parents wanted me to be happy and I just felt so broken. The one thing that felt alien in my family—my brothers were both straight—and in me was the lesbianism.”

The two weeks McCabe spent in a psychiatric facility in Connecticut—“advertised in The New Yorker,” McCabe notes wryly—was a harrowing panoply of aversion techniques that made her vomit, medications that made her feel like a zombie, group therapy with other teens and young adults who were also unhappily gay and what McCabe described as “brutally demeaning talk therapy that made me feel like a disgusting monster that should be hidden from and was dangerous to society if I chose to be a lesbian.” McCabe’s experience underscores how vulnerable teens and young adults can be made complicit in conversion therapy by therapists and others who convince them such treatment will improve their lives and remove the source of conflict.

Conversion therapy in its current form is predicated on a century of methods used to “cure” homosexuality attempted by Sigmund Freud and, later, by his daughter, Anna, as well as some other noted psychoanalysts. Then as now, it was often parents who requested Freud “change” their sons and daughters. Freud was not convinced it was possible to fully change a homosexual to a heterosexual, but that did not stop him or others from trying. Eugen Steinach, a prominent 19th-century Austrian endocrinologist, actually transplanted the testicles of heterosexual men into homosexual men in an attempt to convert them. Immunological problems ended his grim experiments. Steinach didn’t have a similar approach to addressing lesbian sexuality.

During the post–World War II period, when anti-homosexual fervor was hitting a fevered pitch, conversion therapy became increasingly popular. Throughout the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, various forms of reparative therapy became increasingly popular. It wasn’t until the late 1980s when the American Psychiatric Association (APA) eliminated its pathologizing of homosexuality that conversion therapy began to lose some of its luster.

In May 2000, the APA published a position statement on the practice with regard to sexual orientation, asserting it was not a valid treatment for homosexuality and that the “validity, efficacy and ethics of clinical attempts to change an individual’s sexual orientation have been challenged. To date, there are no scientifically rigorous outcome studies to determine either the actual efficacy or harm of ‘reparative’ treatments.”

That was 18 years ago. So why is conversion therapy still so prevalent throughout every region of the U.S.? Why was the first ban on conversion therapy enacted a mere five years ago when Governor Chris Christie signed the New Jersey law on August 19, 2013? The most recent state bans, Maryland and New Hampshire, passed in May and June, and go into effect in January 2019.

There are also 37 cities that have banned the treatment. But those bans have limited impact and don’t mean conversion therapy is not still being performed in those jurisdictions or just outside those city limits. My own city, Philadelphia, banned conversion therapy for minors in July 2017, yet a quick Google search reveals a dozen therapists and outreach centers where conversion therapy is available nearby, the closest within walking distance of my home, which is well within the city limits.

Statewide bans also only control therapeutic relationships with licensed counselors. Thus clergy, laypersons and even parents can continue the practice with no legal restraints and licensed counselors can refer clients to those other venues for treatment which certainly implies a tacit approval of the practice.

And those practices can be seemingly mild: Asking a patient if they really want to be gay or trans, and would they change it if they could? A teenager is especially vulnerable to the suggestion that they could escape the familial and societal conflicts and pressures associated with coming out as LGBTQ by just flipping some mental switch. Wearing a tight rubber band on one’s wrist and snapping it every time same-sex desire creeps into one’s consciousness might not seem that dangerous, but it is, as those promoting the California bill note—it comes from the messaging, communicating to that person that because they harbor these desires, they’re not “normal.”

Right now, in the U.S. there are efforts by LGBTQ civil rights activists to ban the practice entirely and concomitant efforts by religious and right-wing political groups to maintain access to such treatments. In Maine, Governor Paul LePage vetoed a bill on July 6 banning conversion therapy for minors based on concerns that it abridged religious freedom. LePage said he did not believe anyone was practicing conversion therapy in the state. If LePage really believed there was no such thing in Maine, then who would have been harmed by his signing the bill into law?

Incidentally, the Williams Institute of the UCLA School of Law debunks LePage’s assertion that conversion therapy isn’t happening in his state—they say it is happening everywhere. In a January 24 press release, the Williams Institute declared that “an estimated 20,000 LGBTQ youth ages 13 to 17 will undergo conversion therapy from a licensed health care professional before the age of 18.” In addition, “approximately 57,000 youth will receive the treatment from a religious or spiritual advisor. These are the first estimates of U.S. youth at risk of undergoing conversion therapy before they reach adulthood.” The researchers also found that nearly 700,000 LGBTQ adults in the U.S have received conversion therapy at some point in their lives, including about half who received it as adolescents. These are extraordinary numbers and point to the level of risk for teens.

But the religious-freedom angle is the new legislative and judicial pivot upon which conservatives are attempting to reanimate the culture wars—and they have full support from the Trump administration. During his presidential campaign, then-candidate Trump claimed he was “better for the gay community” than Hillary Clinton, famously tweeting on June 14, 2016, “I will fight for you while Hillary brings in more people that will threaten your freedoms and beliefs.” It was an anti-Muslim, anti-immigration dog-whistle disguised as pro-gay rhetoric.

In his acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention, Trump claimed he would protect “our LGBTQ citizens from the violence and oppression of a hateful foreign ideology,” again referencing Islam and ISIS. But of course his promises to protect LGBTQ people were empty (but not his promises to antagonize Muslims and immigrants). On Inauguration Day 2017, the LGBTQ pages from the White House website were removed. On September 26, 2017, Trump’s Department of Justice ruled that employers could fire employees for being LGBTQ. On March 24, Trump signed an executive order banning new recruits to the military who are trans.

This animus toward the LGBTQ community from within the Trump administration extends to embracing and even promoting conversion therapy. During the Olympics, openly gay figure skater Adam Rippon was asked how he felt about Vice-President Mike Pence, who was leading the delegation to Pyeongchang and has a long anti-LGBTQ history in both Congress and as governor of Indiana. Rippon said, “You mean Mike Pence, the same Mike Pence that funded gay conversion therapy?”

A spokesperson for the vice-president denied the claims and Pence himself declared it “fake news” in a tweet, but the New York Times and Snopes, among other publications, detailed Pence’s history of embracing conversion therapy and how he had even requested funding for such treatment while in Congress. Pence refused to support funding for HIV treatment, because he didn’t want money “going to organizations that celebrate and encourage the types of behaviors that facilitate the spreading of the HIV virus.” Instead, Pence wanted conversion therapy: “Resources should be directed toward those institutions which provide assistance to those seeking to change their sexual behavior.”

In a religious-freedom amendment Pence proposed to a 2009 hate crimes bill in Congress, Pence feared those who “favor traditional morality” could be prosecuted for hate speech. He referenced “an ad campaign by pro-family groups showing that many former homosexual people had found happiness in a heterosexual lifestyle … The danger here is that people use a hate crimes bill to silence the freedom of religious leaders to speak out against homosexuality.”

Or conversion therapy.

The battle over conversion therapy is heating up, in part due to support by members of the Trump administration’s inner circle via the FRC, the most prominent anti-LGBTQ group in the U.S. FRC’s president, Tony Perkins, helped craft the GOP’s platform for 2016 which included several anti-LGBTQ elements. Many of Trump’s inner circle are connected to FRC, including Pence, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, and Trump’s former chief of staff and head of the RNC Reince Priebus. Trump recently appointed FRC higher-ups to Health and Human Services, including Roger Severino, who now heads HHS’s office for civil rights. Severino has a long anti-LGBTQ history that includes support for conversion therapy.

Trump’s and Pence’s promotion of religious-freedom bills allow for a vast gray area with regard to conversion therapy and other anti-gay practices. DeVos said in the hearings for her confirmation that she doesn’t support conversion therapy, but she and other members of her evangelical Christian family have donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to groups promoting it. Severino most recently worked at the DeVos Center at the Heritage Foundation.

In June, the U.S. Supreme Court found in favor of a baker who denied same-sex couples a wedding cake in the case of Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission. A few weeks later, the court sent a florist who had also denied gay and lesbian couples wedding arrangements back to revise their case based on the baker’s—effectively saying the SCOTUS could find in their favor if they reframed their argument.

But it was the case of National Institute of Family Life Advocates v. Becerra that could resonate most profoundly for those wishing to overturn the bans on conversion therapy. Pence long argued that a fundamental breach exists between support for LGBTQ rights and support for religious freedom. In ruling on the NIFLA case, SCOTUS agreed with Pence’s premise. Pregnancy crisis centers, which lie to their clients who come seeking abortions are well within their rights to do so, the court noted, citing religious freedom and the First Amendment.

The arguments against these laws banning conversion therapy all revolve around this same issue of religious freedom and free speech, as evidenced by Trump supporter and Maine governor LePage vetoing the recent Maine ban. They minimize the impact of conversion therapy by claiming it’s “just” talk therapy to address same-sex attraction in minors, relying on the concept that teens can’t be sure they are really gay. Proponents of conversion therapy assert that these laws violate the rights of parents and children to seek counseling that conforms to their values and that they also endanger First Amendment rights. The NIFLA case came from California. That makes the AB 2943 bill even more attractive to those actively seeking to overturn existing bans. The NIFLA provides a precedent by which the court could indeed find conversion therapy a matter of religious freedom.

Legal scholars are concerned the SCOTUS will, with the addition of Brett Kavanaugh to the court, overturn existing bans on conversion therapy using the same religious freedom argument as was used for the cake shop and the crisis pregnancy centers.

In addition, conservative jurists have been proffering their own argument: that the proposed bill in California, AB 2943, will curtail adult rights on myriad levels, most importantly that of religious freedom. If that bill passes—it is scheduled for debate when the legislature returns from summer recess on August 6—it could become the test case for Trump’s new SCOTUS on conversion therapy. The bill, which was proposed in April, has been targeted by a variety of religious groups. For these reasons, LGBTQ-rights activists who oppose conversion therapy want the subject raised by Democrats during the Senate Judiciary hearings for Kavanaugh, which are expected next month if the Senate does not recess.

The fight over conversion therapy is being waged daily in the courts and state legislatures between advocates and detractors. This November, just before midterms will see the release of the highly anticipated film Boy Erased, based on Garrard Conley’s memoir of his experience with religious conversion therapy as a youth. It stars Nicole Kidman, Russell Crowe, and Oscar nominee Lucas Hedges, and if the trailer is any indication, the film offers a brutal portrait of the physical and psychological treatment Conley suffered, at the behest of his father who desperately wanted to make his son straight. Will bringing the issue of conversion therapy to the big screen with actors of this caliber raise new awareness of the issue to middle America? Possibly. But for now, thousands of teens and adults are still undergoing this brutal, futile, pointless torture instead of finding a way to embrace who they really are.

Before you go, we hope you’ll consider supporting DAME’s journalism.

Today, just tiny number of corporations and billionaire owners are in control the news we watch and read. That influence shapes our culture and our understanding of the world. But at DAME, we serve as a counterbalance by doing things differently. We’re reader funded, which means our only agenda is to serve our readers. No both sides, no false equivalencies, no billionaire interests. Just our mission to publish the information and reporting that help you navigate the most complex issues we face.

But to keep publishing, stay independent and paywall free for all, we urgently need more support. During our Spring Membership drive, we hope you’ll join the community helping to build a more equitable media landscape with a monthly membership of just $5.00 per month or one-time gift in any amount.